ROBERT HELMAN

Exhibition: May 11 – June 10, 2023

The creation of the world, from matter to light

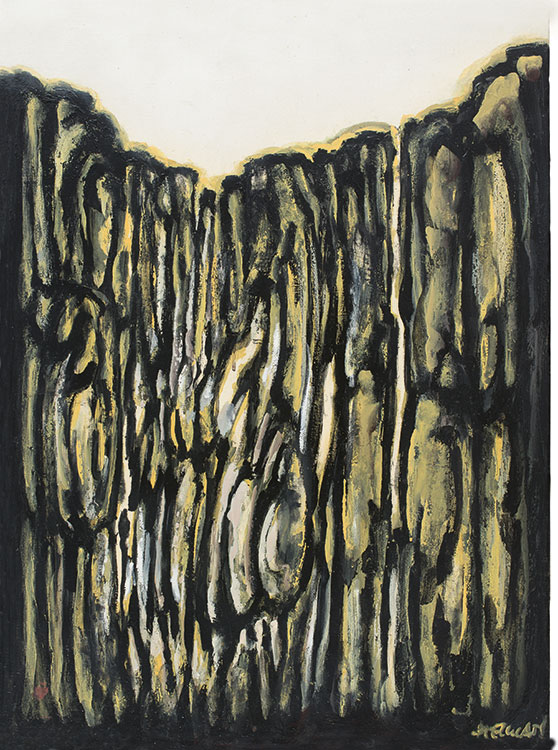

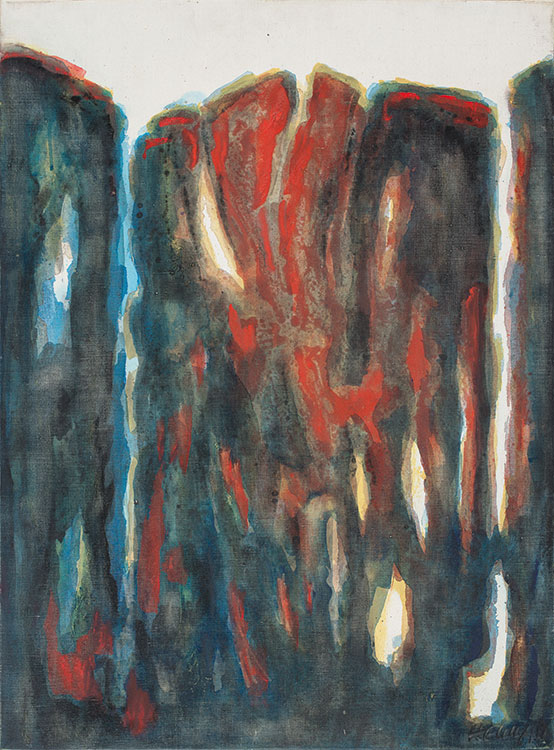

Robert Helman’s first solo exhibition at the Diane de Polignac Gallery showcases a selection of works on Genesis, a theme that was conceived by the artist in the mid- 1940s. Born in Romania along the banks of the Danube in 1910, Helman developed a sense of the natural elements from an early age as he explored the forests of the Carpathians and the landscapes stretching from the Danube to the Black Sea. It was the landscapes of the Sierra de Gredos that would have a defining impact on Helman later on, during the years that he spent in Spain during wartime. Born into a Jewish family, Helman left Romania for Paris as a young man following the introduction of a university quota for Jewish students. Helman’s discovery of the City of Light in 1927 was a dazzling experience that plunged him into a world of intellectual richness until the outbreak of the Second World War, which he lived through on Iberian soil. On his return to France when it was liberated, the country was in ruins; with everything to be rebuilt, the possibilities were endless. Helman then set out to recreate a world born of chaos, which the painter put in order, like a demiurge. The result was the “Genesis” series, also known as the “Landscapes of Genesis”. With expanding, sensual and even erotic larval forms, these compositions give birth to a universe in the making, in which the telluric and the celestial remain connected to each other. The earth, from which all life is born and to which everything returns, is perceived as a matrix pattern of creation. These generative worlds were struggling to free themselves from the medium and Helman turned to colour – with the lively, sensory qualities that it can convey – to express the reality of the world, as with the elements. The colour breathes energy and life into the composition. Movement can be perceived in this process of gestation and parturition. A love of colour and gesture, within the impregnation of the medium laid on the canvas, has taken hold of the artist in a generative gesture. These living forms in perpetual emergence generate a force that penetrates the bowels of the medium.

Genèse – 1945 – Huile sur bois – 75 x 105 cm

Collection privée

Genèse – 1946 – Huile sur bois – 52 x 66 cm

Collection privée

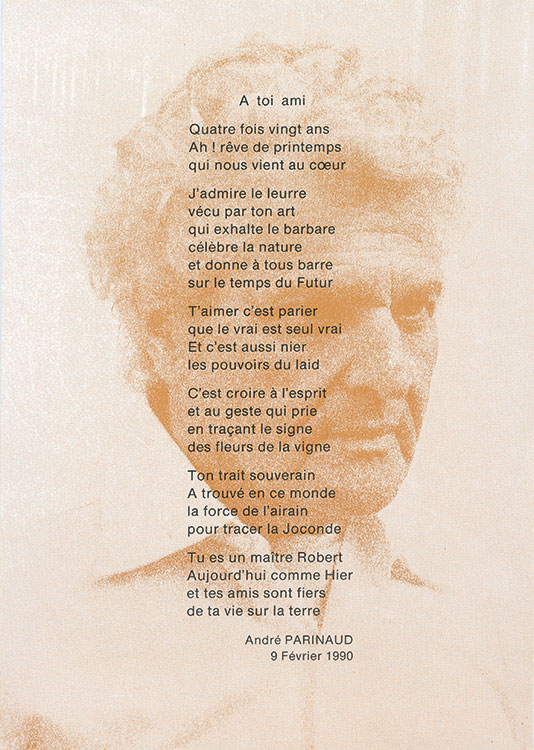

Critics have been unanimous in recognising Helman as a singular painter beyond affiliation with any movement, defined as somewhere between ‘warm’ (lyrical, informal) abstraction and ‘cold’ (geometric) abstraction. The artist himself admitted that he did not fit into the Paris School, claiming to support “anti-aestheticism”. That freedom defined the artist, who tirelessly pursued his artistic investigations to transcribe the “rhythms of life”, punctuated by the alternating seasons. The reason that André Parinaud saw a “great Jansenist austerity”1 , the ferment of “painting by painting”, in his paintings, was because Helman was inhabited by grace, a quality associated with the predestined being according to the doctrine of Jansenism. He would also speak of the artist as a “believer in painting”2 , a crucial definition of Helman’s place in the history of 20th-century art, at a time when painting – which had been discredited and subject to decades in purgatory – was regaining its rightful place as an ideal medium for expressing the disruptions and violence of the contemporary world. Helman always believed in the truth of painting and its power to convey emotion and strength. Recollections of sensations and memories from the artist’s childhood constructed his personal universe, in which the image (the work) became incarnate. As Helman explained in interviews with his friend and critic Max-Pol Fouchet, he was searching for this “double image” (Doppelgänger), in an attempt to perpetuate a memory of this sensory image even after the viewer has turned their eyes away from the work itself. As early as 1949, the artist had taken note of the minor part played by the representation of the object in his notebooks, insisting on the primacy of the “result of the impact between the object and the subject. To the extent that the sensation or emotion contained in the objective form will appear in the painting.”3

1 – André Parinaud, “Helman: poésie pure”, featured in an exhibition catalogue, Galleria Guglielmo Tell, Chiasso, 1977

2 – André Parinaud, “Le chant profond de Helman”, Arts, No. 196, November 1979

3 – Robert Helman, quoted in Helman by Jean Bouret, Paris, Les Gémeaux, 1951, p. 23

Hommage d’André Parinaud pour les 80 ans de Robert Helman, 9 février 1990

Photo : Jean Louvel

Carton d’invitation pour la 1ère exposition de Robert Helman à Paris, Galerie Berri-Raspail, 1947

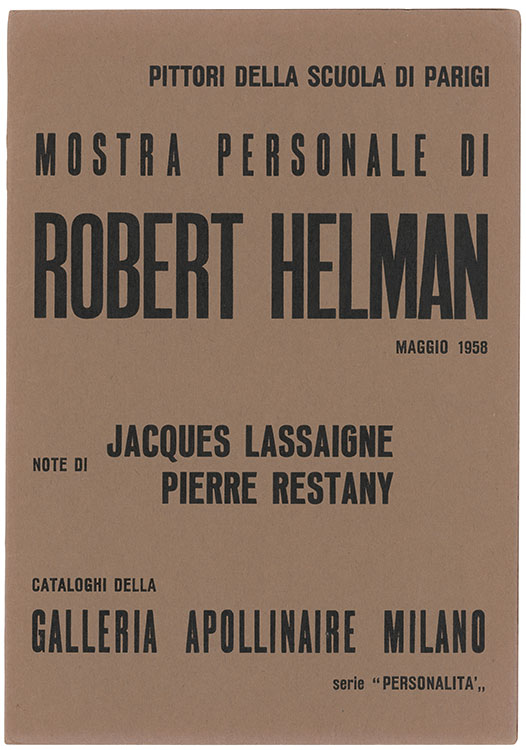

Pierre Restany was not mistaken in considering that Helman was “taking over from an exhausted form of calligraphy, afflicted by the sclerosis of functional vocabularies.”4 At the beginning of the 1950s, certain artists, such as Georges Mathieu and Jean Degottex, turned to a form of gesture, which occupied a space freed from the perspective inherited from the Renaissance. This gesture was joined by the void that the artist would confront when faced with the canvas, with the annihilation of any reference to nature, aesthetic or model, according to the theory of lyrical abstraction defined by Mathieu. Helman rejected this understanding of painting, which, for him, had to be a matter of poetry and free will. The living and Nature were at the heart of the artist’s investigations; he was always moved by life and in search of life-giving elements in perpetual metamorphosis. Helman’s Genesis works were followed by woodland themes (Forests, Trees and Roots) and the telluric forces of the world (Germination and Flight, etc.). The pictorial support was also very important to the artist, who did not hesitate to use tree bark – or “coats of skin” according to the term in Latin – from which new cosmogonies were born. With a Bachelardian view of the life of the medium, the artist made judicious use of the plant-like roughness – with varying levels of coarseness – of the bark to bring these hidden worlds to life. With material substance and flamboyance, Helman’s Genesis works have pushed back the boundaries of space, emerging free into rays of light that pierce the tight mesh of lines in a struggle of contradictory forces of life over the original void. Helman’s forms have created a unified movement in the light of the palette, giving a voluptuous and erotic quality to the first Genesis works from the 1940s; from the following decade onwards, these original worlds would become ordered with a rising dynamic or carried away by the composition’s centripetal force, testifying to the pervasive instability of a universe yet to take form. Rooted in these generative worlds, the essence of Helman’s paintings and the distinctive nature of his language invite us on a timeless, inner journey.

Clotilde Scordia

Art critic and historian

4 – Pierre Restany, “Les signes organiques d’Helman”, in an exhibition catalogue, Galleria Apollinaire, Milan, 1958

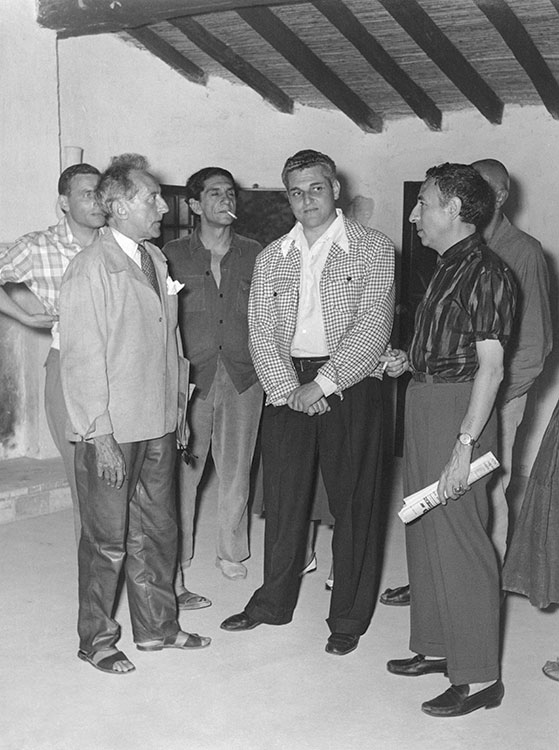

Robert Helman et Pierre Restany Galleria BLU, Milan, 1958

Photo : Attualfoto, Milan

Dépliant de l’exposition Robert Helman Galleria Apollinaire, Milan, mai 1958

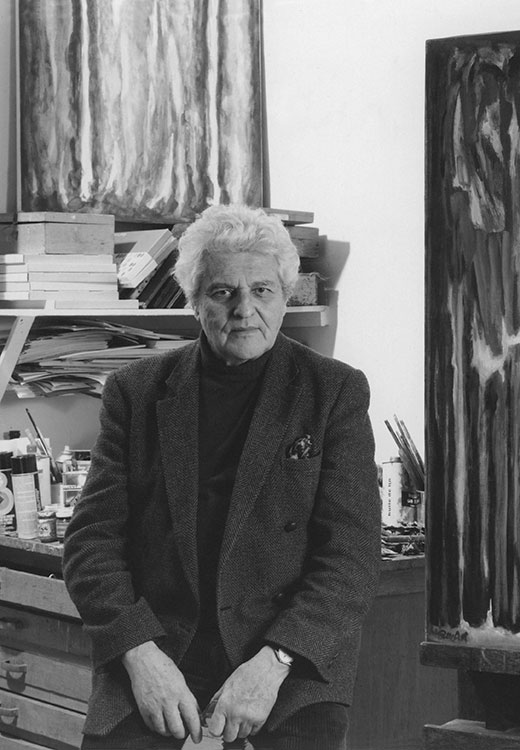

Robert Helman dans son atelier du Fort Jacquet, 1972

Robert Helman lors d’un vernissage Galerie La Pochade, Paris, 5 juin 1986

Exhibited artworks

Genèse, 1956

Oil on canvas

130 x 89 cm – 51.2 x 35 in.

Signed and dated “HELMAN 56“ lower left

Exhibitions

Rétrospective, Helman, peintures et sculptures, Musée d’Art moderne, Troyes,16 avril – 13 juin 1994

Robert Helman, Galerie Nicolas Deman, Paris, 15 juin – 15 juillet 2000

Bibliography

Rétrospective, Helman, peintures et sculptures, catalogue d’exposition, Musée d’Art moderne,

Troyes, 1994, cat. n° 30, p. 12

Lydia Harambourg, Robert Helman, catalogue d’exposition, Galerie Nicolas Deman, Paris, 2000,

repr. p. 15

Genèse, 1965 ca.

Oil on canvas

80 x 60 cm – 31.5 x 23.6 in.

Signed “HELMAN“ lower right

Genèse, 1968 ca.

Oil on canvas

92 x 73 cm – 36.2 x 28.7 in.

Signed “Helman“ lower left

Exhibition

Robert Helman, Galerie Nicolas Deman, Paris, 15 juin – 15 juillet 2000

Bibliography

Lydia Harambourg, Robert Helman, catalogue d’exposition, Galerie Nicolas Deman, Paris, 2000,

repr. p. 29

Genèse, 1974

Acrylic on canvas

92 x 65 cm – 36.2 x 25.6 in.

Signed and dated “Helman 74“ lower right

Genèse, 1975

Acrylic on canvas

81 x 60 cm – 31.9 x 23.6 in.

Signed “Helman“ lower right

Signed “Helman“ on reverse

Exhibitions

Genèse – paysage imaginaire, Galerie Gordon, Tel Aviv. En collaboration avec la revue Arte Mercato, mai 1977

Genèse – paysage imaginaire, Galleria Guglielmo Tell, Chiaso. En collaboration avec la revue Arte Mercato, juin 1977

Rétrospective, Helman, peintures 1943-1983, Musée d’art moderne de Paris, Orangerie de Bagatelle, 10 mai – 13 juin 1983

Bibliography

« Robert Helman », numéro spécial pour l’exposition à la Galleria Guglielmo Tell, Genèse – Paysage imaginaire, Arte Mercato, Milan 1977, repr. p. 4

Jean Duvignaud, Françoise Marquet, Helman, peintures 1943-1983, catalogue d’exposition, Musée d’art moderne de Paris, Orangerie de Bagatelle, Paris, 1983, cat. n° 42.

Genèse, 1975 ca.

Acrylic on canvas

73 x 60,5 cm – 28.7 x 23.8 in.

Signed “Helman“ lower left

Forêt, 1976

Acrylic on canvas

92 x 65 cm – 36.2 x 25.6 in.

Signed “HELMAN“ lower right

Exhibitions

Robert Helman : Genèse – Paysage imaginaire, Galerie Gordon, Tel Aviv, mai 1977

Robert Helman : Genèse – Paysage imaginaire, Galleria Guglielmo Tell, Chiaso, juin 1977

Robert Helman, Galerie Nicolas Deman, Paris, 15 juin – 15 juillet 2000

Bibliography

André Parinaud « Poésie pure », Max-Pol Fouchet, catalogue de l’exposition Robert Helman : Genèse – Paysage imaginaire, Galleria Guglielmo Tell, Chiaso, en collaboration avec la revue Arte Mercato, Milan, 1977, repr. p. 4

« Robert Helman », revue Arte Mercato, 6 ème année, n°1, Milan, 1977, repr. p. 274

Lydia Harambourg, Robert Helman, catalogue d’exposition, Galerie Nicolas Deman, Paris, 2000, repr. p. 29

Genèse, 1980 ca.

Acrylic on canvas

65 x 54,5 cm – 25.6 x 21.5 in.

Signed “Helman“ lower left

Exhibition

Paysage de la Genèse, Galerie Mayanot, Jérusalem, 20 avril – 12 mai 1986

Genèse, 1981 ca.

Acrylic on canvas

92 x 65 cm – 36.2 x 25.6 in.

Signed “Helman“ lower right

Genèse, 1982 ca.

Acrylic on canvas

162 x 130 cm – 63.8 x 51.2 in.

Signed “Helman“ lower right

Exhibitions

Rétrospective, Helman, peintures 1943-1983, Musée d’art moderne de Paris, Orangerie de Bagatelle, Paris, 10 mai – 13 juin 1983

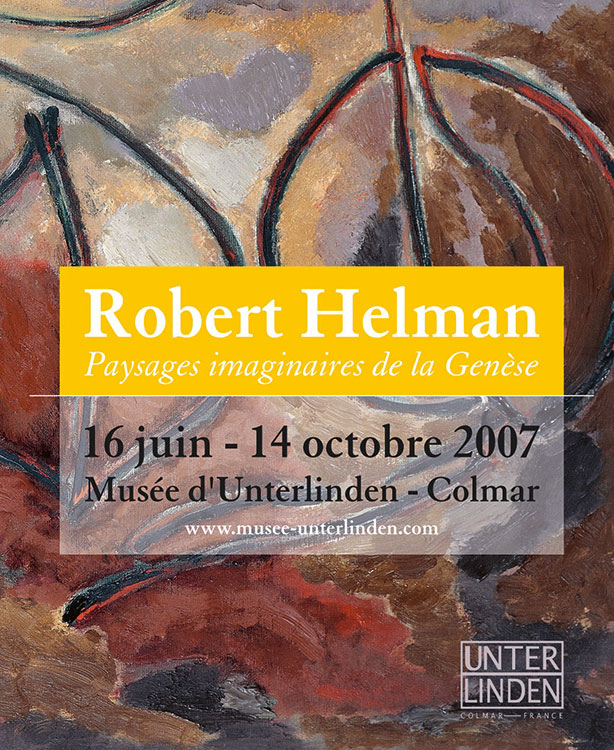

Les paysages imaginaires de la Genèse, Musée Unterlinden, Colmar, 16 juin – 14 octobre 2007

Rétrospective Robert Helman 1910-1990, Orangerie des Musées de Sens, Sens, 27 juin – 26 septembre 2010

Bibliography

Jean Duvignaud, Françoise Marquet, Helman, peintures 1943-1983, catalogue d’exposition, Musée d’art moderne de Paris, Orangerie de Bagatelle, Paris, 1983, cat. n° 58

Lydia Harambourg, Robert Helman, monographie, Musée Unterlinden en co-édition avec Somogy, Paris, 2007, repr. p. 44

Genèse, 1986

Acrylic on canvas

162 x 130 cm – 63.8 x 51.2 in.

Signed and dated “Helman 86“ lower right

Exhibitions

Helman – 50 ans de peinture, Galerie Eterso, Cannes, 15 juin – 14 juillet 1990

Rétrospective Robert Helman 1910-1990, Orangerie des Musées de Sens, Sens, 27 juin-26 septembre 2010

Bibliography

Jean-Marie Tasset, « L’appel de la lumière », catalogue de l’exposition Helman – 50 ans de peinture, Galerie Eterso, Cannes, 1990, repr. planche 8

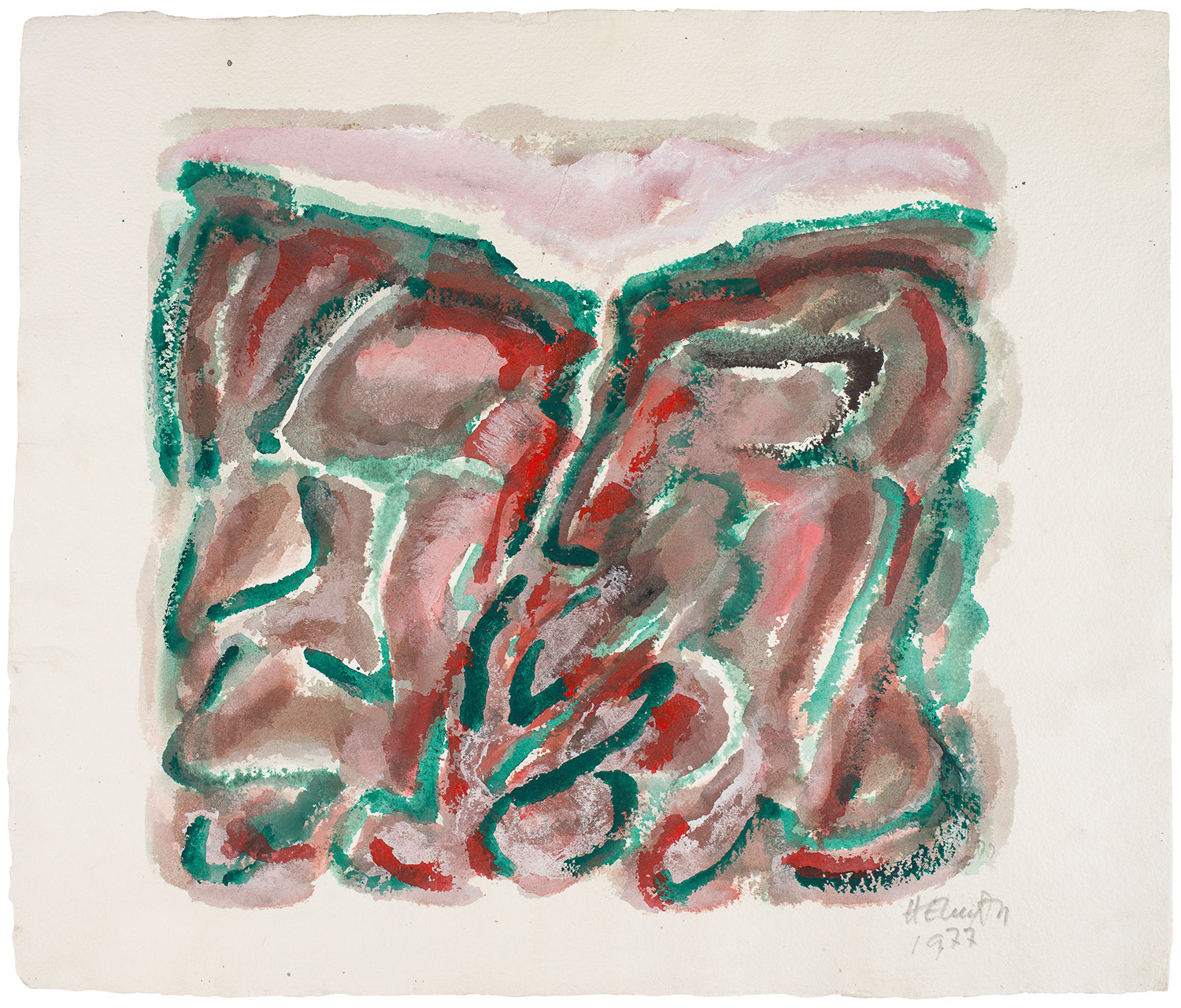

Genèse, 1977

Gouache on paper

39 x 50 cm – 15.4 x 19.7 in.

Signed and dated “Helman 77“ lower right

Genèse, 1976 ca.

Gouache on paper

50 x 42 cm – 19.7 x 16.5 in.

Signed “Helman“ lower right

Genèse, 1982 ca.

Gouache on tree bark paper

64,5 x 49 cm – 25.4 x 19.3 in.

Signed “Helman“ lower left

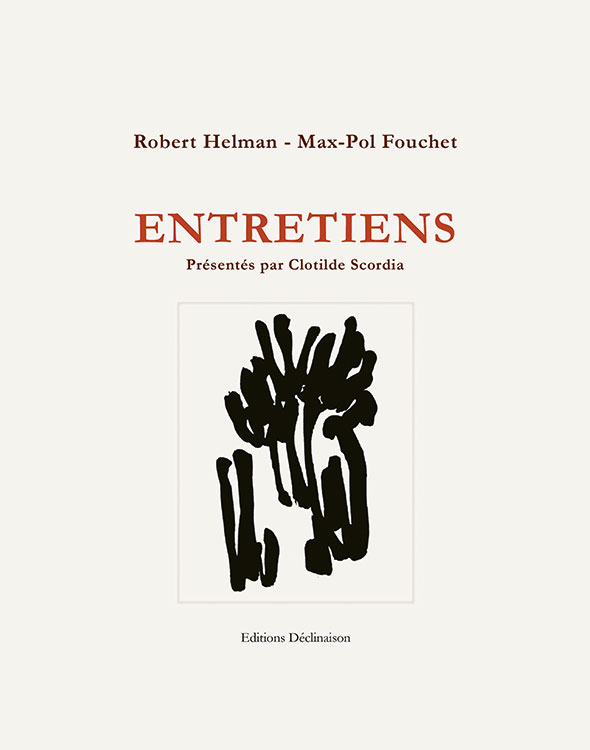

ENTRETIENS

Robert Helman & Max-Pol Fouchet

Entretiens présentés par Clotilde Scordia

Format : 19 x 23,5 cm, 112 pages,

Illustrations : 7 encres N&B

Planche couleurs en hors texte

Parution le 5 mai 2023

Diff. & dist. Les Belles Lettres

ISBN 978-2-9553310-8-8

This exhibition accompanies the publication of Clotilde Scordia’s ENTRETIENS: Robert Helman & Max-Pol Fouchet by Déclinaison.

In June 1975, the poet and art critic Max-Pol Fouchet asked his friend, the painter Robert Helman, to interview him about his creative process. The two men met twice in the painter’s studio in Paris’ Montparnasse district and their discussions were recorded and transcribed in this book.

Prompted by Max-Pol Fouchet in these conversations, the artist Robert Helman reveals the origins of his pictorial intentions and his understanding of the role of painting. In doing so, Helman sets out – with rare clarity – the difficult issues that artists must address in order to achieve the profound harmony that unites personal and artistic truth.

ENTRETIENS : ROBERT HELMAN ET MAX-POL FOUCHET (extracts)

Max-Pol Fouchet: What was the theme of this very first exhibition?

Robert Helman: It was the imaginary landscapes of Genesis, a very free style of painting. I didn’t call it abstract yet because in my mind it wasn’t abstract; it was about the landscapes of the creation of the world.

M-P F: Why this subject? Did you choose it or did it present itself to you?

R H: It presented itself to me. You know, I’m very wary of the titles that are given to paintings. They are very often invented after the fact. In fact, I created these landscapes in connection to Spain. The impact that the country had on me was very strong, and probably, the pictorial repercussion was just that.

M-P F: An impact provoked by the landscapes in Spain?

R H: By the Spanish landscapes and the light, yes, the sierra de Gredos. But I wasn’t working in the spirit of the silver tones of Velázquez, the silvery greys – because he put the landscape in the background and there was always a scene in the foreground. It has a very rhythmic, very constructed quality to it. For me, it was the landscape that came to the foreground, where it would inscribe things that were quite free with an inner rhythm.

––––––––––

M-P F: But your imaginary landscapes of Genesis were not only artistic in form; they were also intellectual, isn’t that right?

R H: It was about consciousness, the intellectual, but in the execution, it came out in an artistic form. I put this exhibition on again in 1947, immediately after the Liberation, at the Galerie Berri-Raspail, then in the Galerie Kaganovitch, on Boulevard Raspail. It was perceived as a major exhibition with a strangely prefaced catalogue by my friend Maurice Nadeau who detected in my paintings “the trace of our wounds inflicted by the horrors of war”.

Genèse – 1969 – Huile sur toile – 130 x 162 cm

Musée d’Art moderne, Troyes

Genèse – 1972 – Huile sur toile – 100 x 81 cm

Musée des Beaux-Arts, Sens

M-P F: Nadeau was the historian of the Surrealist movement, wasn’t he?

R H: Exactly, and Nadeau never wrote another preface because his friends resented him for writing about a non-Surrealist painter. But we remained great friends. So that was my first Parisian event. My imaginary landscapes of Genesis were painted with a rather elaborate temperament, with a sensuality, perhaps even a certain eroticism. It was the era of Surrealism and at the time, our idol was Prévert, who had brought about a poetry revival.

M-P F: And André Breton?

R H: Breton too and the whole Surrealist school. As you said, Maurice Nadeau was writing his “History of Surrealism”, and it was all about the ideas that were being stirred up, and I was steeped in that milieu. As I come from Romania, I was a friend of Victor Brauner, who lived the Surrealist adventure authentically. He had to be crazy – according to Surrealism – and well, he really was! And the same Surrealists who had told him that he had to be crazy, well, when they encountered him they switched to the other pavement and said: “Oh la la, he’s going to jinx us, here comes the madman!”

M-P F: His famous missing eye!

R H: That’s it! Which he painted just before he lost it! I was also a friend of Oscar Dominguez. I spent time with all of them, the Surrealists, but to save myself, somewhat intuitively, I only took from Surrealism the eroticism, the freedom to dig deep into sensuality. And so, I created this series, the Imaginary Landscapes of Genesis, which had a kind of erotic and sensory temperament.

––––––––––

M-P F: When you talk about your Genesis Landscapes, am I right that you are talking about the creation of the world?

R H: Yes, and it also relates to parturition.

M-P F: What does that mean?

R H: It means to give birth. The creation of the world.

M-P F: According to the literal meaning of the word parturition. Robert Helman: Yes, exactly, in the literal sense. A certain vibration of matter in relation to the centralisation of the organism, if you like.

M-P F: You had a very decisive palette, with a strong sense of chromatics.

R H: That came from the Spanish influence. I worked, and I still work, with the palette of Velázquez, i.e. the seven colours, and very rarely with metallic colours, very rarely with chromes, very rarely with metallic pigments. In general, I used earth tones, red earth tones, ochre tones and broken earth tones, so as not to use hard, metallic colours.

M-P F: With your Genesis works, am I right that you were never interested in illustrating the biblical words “In the beginning…”?

R H: No, there was no symbolism at all.

M-P F: So, was it a very personal Genesis?

R H: I believe I can assure you that from an ideological point of view, my great struggle was to break away from Surrealism. Although, I was fascinated by the great trends in Surrealist thinking, the exploration of the subconscious, both in the psychological field and in the field of literature, because good literature is life.

––––––––––

M-P F: (…) The essence of many of your paintings is expressed in the very word “Genesis”. Why did you choose to call these paintings “Genesis”, and why are you interested in this? Is it because it relates to something in the making, something that changes, something that expresses a force of action, a force of transformation? At its essence, it is not eternity. It is the process of life.

R H: I would agree with that. When I say “eternity”, the word “becoming” is implicit.

M-P F: For you, eternity is becoming?

R H: Yes, it is.

M-P F: It is not an abstract eternity, it is not a fixed or idealised form of eternity, it is an eternity in motion.

R H: It is in the process of becoming. And this becoming is the path to the future, it’s always the same thing that I come back to. Every time I make a painting, I try to give it an energy, a vitality that carries this possibility of becoming. It is more than an evolution, it is an intuition, a feeling of becoming.

M-P F: Yes, a friend of mine who is now deceased told me that you combine the reveries of the earth with the reveries of fire. I am, of course, talking about Gaston Bachelard.

R H: I liked reading Bachelard very much.

Genèse – 1973 – Huile sur toile – 97 x 130 cm

Musée des Beaux-Arts, Sens

Genèse – 1978 – Huile sur toile – 100 x 73 cm

Musée des Beaux-Arts, Dijon

M-P F: What also strikes me in your “Genesis” works is a very strong, very powerful cosmic feeling, which you express through forms in the process of being created. I see things rising up, as if the molten clay was trying to find a human form, while elsewhere there are monsters, birds… and the coils of an original, early Baroque style. Is that the case? I think it all started with the Baroque style.

R H: I don’t object to the Baroque style at all. I consider Baroque to be a very superior form of art. I have always felt more moved by the cathedral in Santiago de Compostela than by some monuments, even the most prestigious Gothic ones. I consider the Baroque style to be a very important form of art, in which the line breaks, starts out and returns, and it is an eternal form of beginning again. I do not, therefore, contest the Baroque element. I would, however, like to highlight a notion – not deliberate, not philosophical – but rather a profound feeling that makes me think that the world is in a spiral. And that in reality, it is the spiral that closes the circuit of our thinking, and therefore of our existence. I have a sense of this spiral. And this spiral is the sign of infinity; it gives us a feeling, even if we have to die, that life is bearable for us because there is a beginning, and therefore a feeling of eternity. Eternity may not exist, but the feeling of eternity can exist. So it is this spiral that I come back to, more than the Baroque.

––––––––––

M-P F: So you started with this sort of grand geological vision of the world, the creation of the earth, the sky, the stars, without it being very precise, at the same time. In essence, it is a kind of genesis – not abstract, of course – but it is the very substance of the world, it’s not the world you created, it’s something else.

R H: Which is to say that it is never truly geological in nature. In itself, geology, the love of rocks, is not interesting. It is only interesting to the extent that the rock is part of me.

M-P F: The raw material is you.

R H: It is man, yes. When I make simple strokes, simple gestures, it is my presence that I am asserting. I consider gesture not in an abstract way in and of itself, but as a vital extension of my hand. I consider gesture as part of me. As writing can only be a prolongation of the inner self, it must obey all the eurhythmics of my organism. And that was, even for me, the fundamental approach to my whole understanding of creation. I’ve thought a lot about the question of creation. It is naturally possible to create by conceiving intellectually, and by thinking of the world, but this was not within my intellectual means. I had to restrict myself to my organism, to the perception I had taken from my physical existence and as such, and from there, I resonated with nature and I thought that if I could register a small truth from my organism, from my consciousness, from the perception of

my own existence, then I would have a very good chance of being in truth. And I must say that after 35 years of working in this direction, I am still discovering things, still marvelling at the resonance that I can still find. I believe that I will grow old and die without telling myself that I have lost my way. Because I have made a physical work, a work of the flesh.

––––––––––

M-P F: (…) Something that strikes me in your painting, is its simplicity, well its artistic simplicity if you like. And indeed, simplicity is not the word I should use, but rather a kind of austerity. There is an almost monastic approach. You want to make contact with certain natural forces, with telluric forces, such as forests or perhaps the landscapes of Genesis, and this could result in an over-abundance. But in your work, on the contrary, there is always a kind of reduction to the essentials.

R H: Many critics have written about what I do, but I must say that one day, I had the great satisfaction of having Jean Cocteau visit one of my exhibitions in St Paul de Vence. He came in, took a look around, and then turned to me like a man who didn’t have much to say, and then, suddenly, he said: “One can sense that you are looking for the essential rhythms of life.” I was left confused, struck by his insight.

Genèse – 1980 – Huile sur toile – 100 x 73 cm

Musée Unterlinden, Colmar

Genèse – 1982 – Huile sur toile – 162 x 130 cm

Fonds municipal d’art contemporain, Paris

Biography

Robert Helman (1910-1990)

ROBERT HELMAN: FROM CHILDHOOD IN ROMANIA TO STUDIES IN PARIS

Robert Helman was born on 9 February 1910 in Galati, Romania, where the Danube joins the Black Sea. Helman’s grandfather was the chief rabbi of the Kaiser in Vienna, while his father was a merchant and the owner of an alcohol distillery. His mother, meanwhile, was the president of an orphanage. She played a key role in his education, first hiring a violin teacher for her son – who showed no interest in music – and then an art teacher to give instruction in drawing and painting, lessons that would spark a real passion in the child.

Helman, who had been immersed in French culture through childhood, obtained his baccalaureate at the age of 17, at which point he expressed a desire to go to France for a university education. Quotas had been introduced in Romania at that time limiting the number of Jews that could be admitted to universities in the country. Helman’s parents accepted his decision on the condition that he studied law or medicine, which he did, enrolling at the Faculty of Law on his arrival in Paris in July 1927. The young student quickly became an activist, developing close connections with Trotskyist students such as the future writer and editor Maurice Nadeau, whose portrait Helman would later paint.

Robert Helman graduated with a law degree in 1931. During a trip back to his hometown, the young graduate met Zéna Jolles, who was also a student in Paris. Back in the French capital, they campaigned for political causes together, engaging in lengthy discussions about the Spanish war and the rise of Nazism in Germany. Zéna and Robert married in Romania in 1936, after which they returned to Paris where the latter worked for some time as a lawyer.

ROBERT HELMAN’S EXILE IN BARCELONA

In September 1939, Robert Helman volunteered for the French Army but was not enlisted because he was a Romanian citizen. Thanks to their connections with Trotskyist circles, Zéna and Robert were warned in advance of Hitler’s offensive in France and decided to leave Paris immediately to take refuge in Barcelona. The couple were able to cross the border with the help of false baptismal certificates obtained from the parish priest of the Saint-Germain-des-Prés church in Paris.

The couple found themselves destitute and had to sell their personal possessions and wedding rings. It was particularly difficult for them to find work because neither Zéna nor Robert could speak Spanish. Zéna found a job as an assistant in a hospital nonetheless, while Robert had to take on casual work waiting tables and delivering goods, among other odd jobs, despite his law degree. The couple met many refugees in Barcelona who were settling in Spain or travelling to Portugal or South America.

Just as it had during the First World War, Barcelona welcomed many European artists during this period. It was in this climate that Robert Helman began experimenting with painting. Looking for work, he entered a cobbler’s shop to make inquiries. The cobbler asked him what he liked to do, and Helman replied that he liked to paint but had no money for materials. The cobbler gave him some money and commissioned him to create a work of art. Helman painted a still life of flowers, which the cobbler immediately sold for twice the amount given to the artist. As the artist recalled, “That was the beginning of my career as a painter.”

Nature morte – 1944 – Huile sur toile – 27 x 35 cm

Collection particulière

Autoportrait – 1944 – Huile sur toile – 45 x 34 cm

Collection particulière

An excellent portrait painter, Robert Helman thus began to earn a living in Barcelona through his painting. He met the painter Jaime A. Colson, a professor at the Barcelona School of Fine Arts, who taught him fresco techniques and invited him to join the artists’ collective “Los artistas de la Campana de San Gervasio”. The group, which took its name from the café where its members met, included the artists Joan Vilató and Josep Vilató (nephews of Pablo Picasso), Joan Ponç, Antoni Tápies, Modest Cuixart, José María de Sucre and the poet Joan Brossa, as well as the art critic Arnau Puig. In 1945, Helman’s work was shown for the first time in Barcelona in several galleries. The artist had his first solo exhibition in the city at the Galerias Pictoria in November.

THE PAINTER’S RETURN TO PARIS

After the Liberation of France, Zéna and Robert Helman returned to Paris, where the latter devoted himself entirely to painting. Robert moved into the former studio of a friend – the painter Emmanuel Mané-Katz, whom he had met in Barcelona –, taking up residence at 255 Boulevard Raspail in Paris’ Montparnasse district. Zéna Helman, meanwhile, joined Professor Henri Wallon’s child psychobiology team. The couple had lost many friends during the war but were reunited with the publisher Maurice Nadeau, who wrote texts for Robert’s exhibitions. The couple’s son Henri was born in 1947. That year, Robert Helman had solo exhibitions in Paris at the Galerie Berri-Raspail and in Algeria at the Galerie Alsace-Lorraine in Oran and the Galerie Le Nombre d’Or in Algiers.

The year 1948 was marked by a number of important encounters for Robert Helman, who met the Spanish painters Óscar Domínguez and Antoni Clavé as well as the Romanian painter Victor Brauner and the French-Algerian painter Jean-Michel Atlan. This community of artists met at Le Dôme, La Coupole, Le Select, and other cafés in the French capital, which was playing host to numerous foreign artists at the time. That year, Robert Helman exhibited several times at the Galerie Breteau, notably alongside Jean-Michel Atlan, Pierre Soulages, Hans Hartung, Óscar Domínguez and Henri Goetz, among others.

In 1949, Robert Helman and Emmanuel Mané-Katz created a mural – The Tree, 1.30 x 2.10 m – for the Botanical Library in Netanya, Israel. Robert Helman then moved to Saint-Paul-de-Vence in the south of France, where he became friends with the poet André Verdet. The painter only stayed there for eight months, prevented from painting, he said, by the light of the south.

Zéna and Robert Helman became naturalised French citizens on 15 July 1950. Zéna joined the French National Centre for Scientific Research as a research associate at the Hôpital Sainte-Anne in the electroencephalography department.

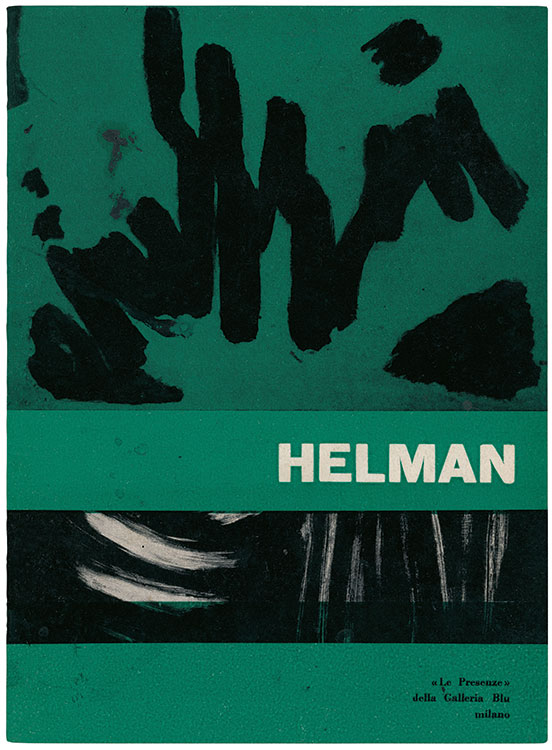

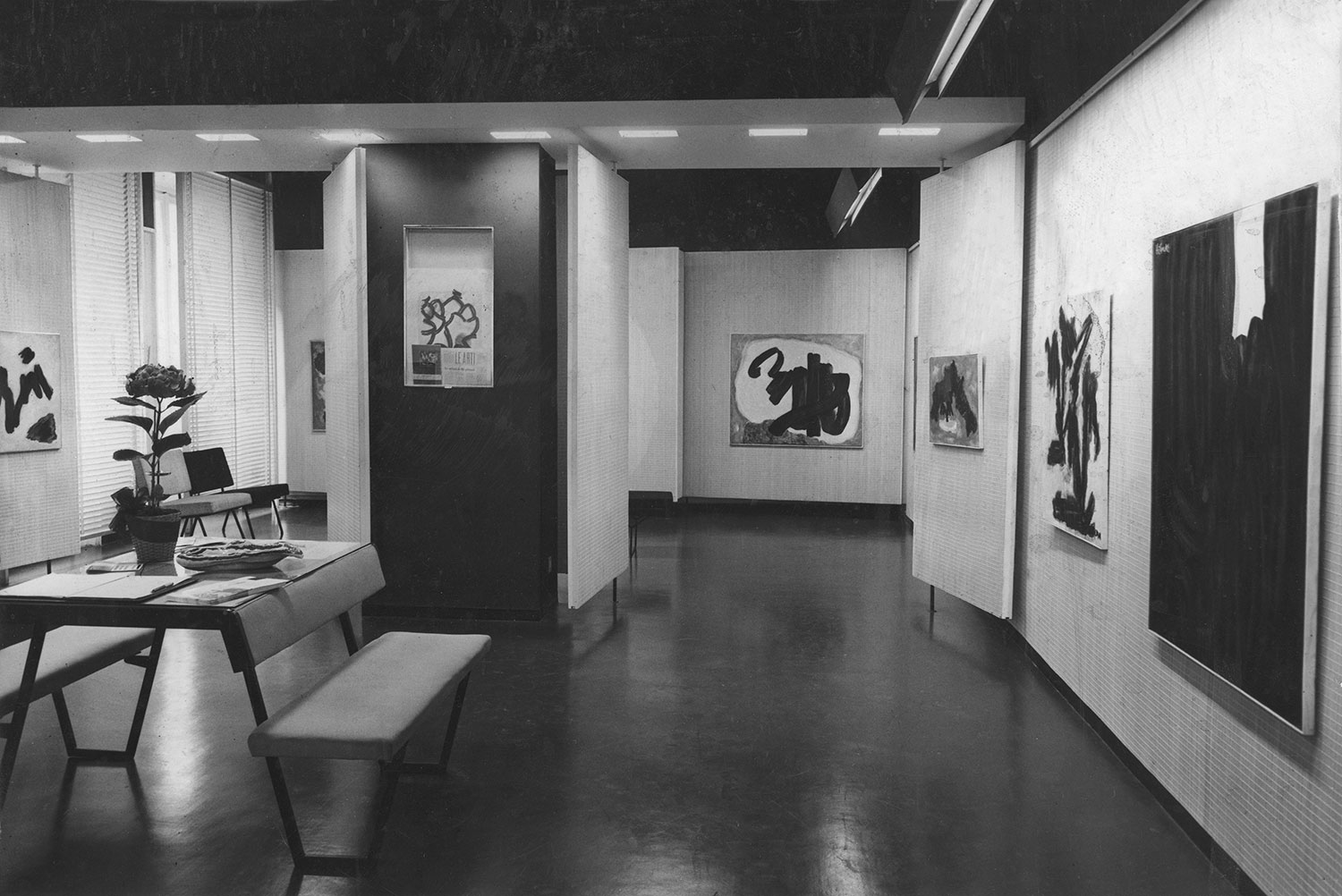

Catalogue de l’exposition Robert Helman, Galleria Blu, Milan, 1958

Vue de l’exposition Robert Helman, Galleria Blu, Milan, 1958

ROBERT HELMAN’S PIVOT AL ENCOUNTERS AS AN ARTIST

Robert Helman’s first monograph was published in 1951 by Les Gémeaux as part of a collection entitled “Les Artistes du temps présent” written by Jean Bouret. In 1952, the painter met the Italian art critic Giuseppe Marchiori who organised a solo exhibition for him at the Galleria Sandri in Venice.

Robert Helman and his son Henri travelled to Canada in 1953. Robert’s parents had moved there after the war and the artist wanted to be with his father, who was undergoing an operation at the time. In Montreal, Robert met the collectors Romeck and Lorette Shefner, who would acquire many of Robert Helman’s works over the next thirty years, creating the largest body of his work in Canada. The painter also had numerous solo exhibitions in Canada.

Robert Helman met Alexander and Stella Margulies in 1955 through his friend Emmanuel Mané-Katz. The prominent London collectors would make annual acquisitions of Robert’s work for more than fifteen years. In the same year, Robert Helman participated in the Salon de Mai and took part in group exhibitions at the Galerie Charpentier and Galerie 73 in Paris. Jean Cocteau – a friend of the artist – bought one of his works, saying: “Your canvas is a landscape where nature and the mind have intimately entwined their essential rhythms.” Robert Helman also met the gallery owner Henri Bénézit, who showed his work on many occasions. In 1958, Robert Helman moved into the former studio of his friend, the painter Óscar Domínguez, at 83 Boulevard du Montparnasse. During the same period, he became friends with the art critic Pierre Restany, who helped to promote his work in France and Italy. In October 1959, Robert Helman’s second monograph was published by

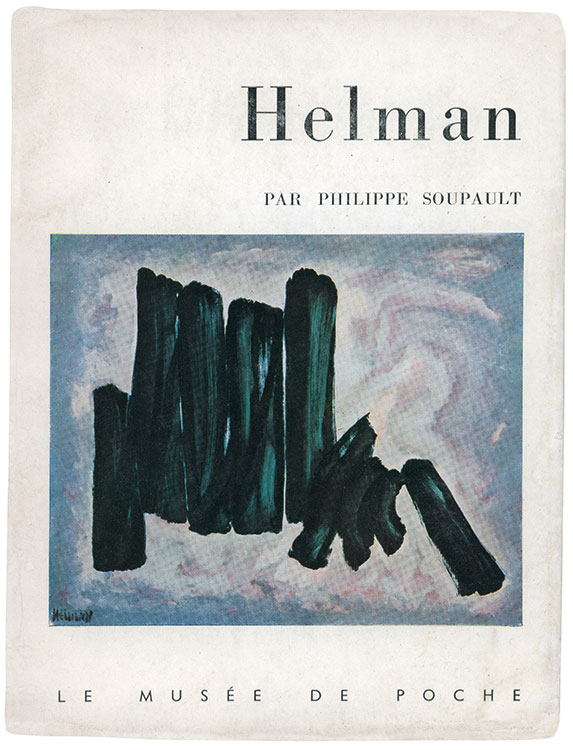

Georges Fall as part of a collection entitled “Le musée de poche” written by Philippe Soupault. The Tate Gallery in London acquired a work by Robert Helman in that same year.

In 1961, Robert Helman met the dealer Gualtieri di San Lazzaro, who would become a friend and show his work at the Galerie du XXème Siècle. The dealer Beno d’Incelli showed Helman’s artwork many times at his Paris gallery

from 1962 onwards, alongside works by Jean Dubuffet, Jean Fautrier, André Lanskoy and Serge Poliakoff. In 1963, the artist developed a relationship with Jean Bauchet, the owner of the Moulin-Rouge and several casinos. An art connoisseur, Bauchet built up the largest collection of Robert Helman’s work in France. Helman also met Harrison and Sonia Eiteljorg – American patrons of the arts whose collection would form the Indianapolis Museum of Art – who acquired many of the painter’s works. From 1964 onwards, the painter’s artworks were regularly exhibited at the Galerie Renée Laporte alongside works by artists such as Olivier Debré, Ladislas Kijno, André Marfaing and Joseph Sima.

THE ARTIST’S STUDIO IN CHAMPAGNE

In 1962, Robert Helman visited the Champagne region of France with his friend, the painter Albert Bitran, who wanted to buy a house there. Helman fell in love with the forest of Othe, which reminded him of landscapes from his childhood on the banks of the Danube. He bought a property in the region, which became his summer studio and then his main residence towards the end of his life.

In 1966, Helman met the art dealer Allan Rich who invited him to participate in the opening of his new gallery – the Stewart-Verde Gallery – in San Francisco. Robert Helman then travelled to Mexico where he discovered wood bark paper, the ideal material for an artist inspired by nature and the forest in particular. He brought a hundred leaves of bark paper back to France and used them for a series of works on trees.

Robert Helman then moved into the former studio of the painter Antoni Clavé at 45 Rue Boissonade – in the 14th arrondissement of the French capital – which he occupied until the end of his life. He left his former Paris studio at 83 Boulevard du Montparnasse to his son Henri, who was then a film student at the Louis-Lumière film school.

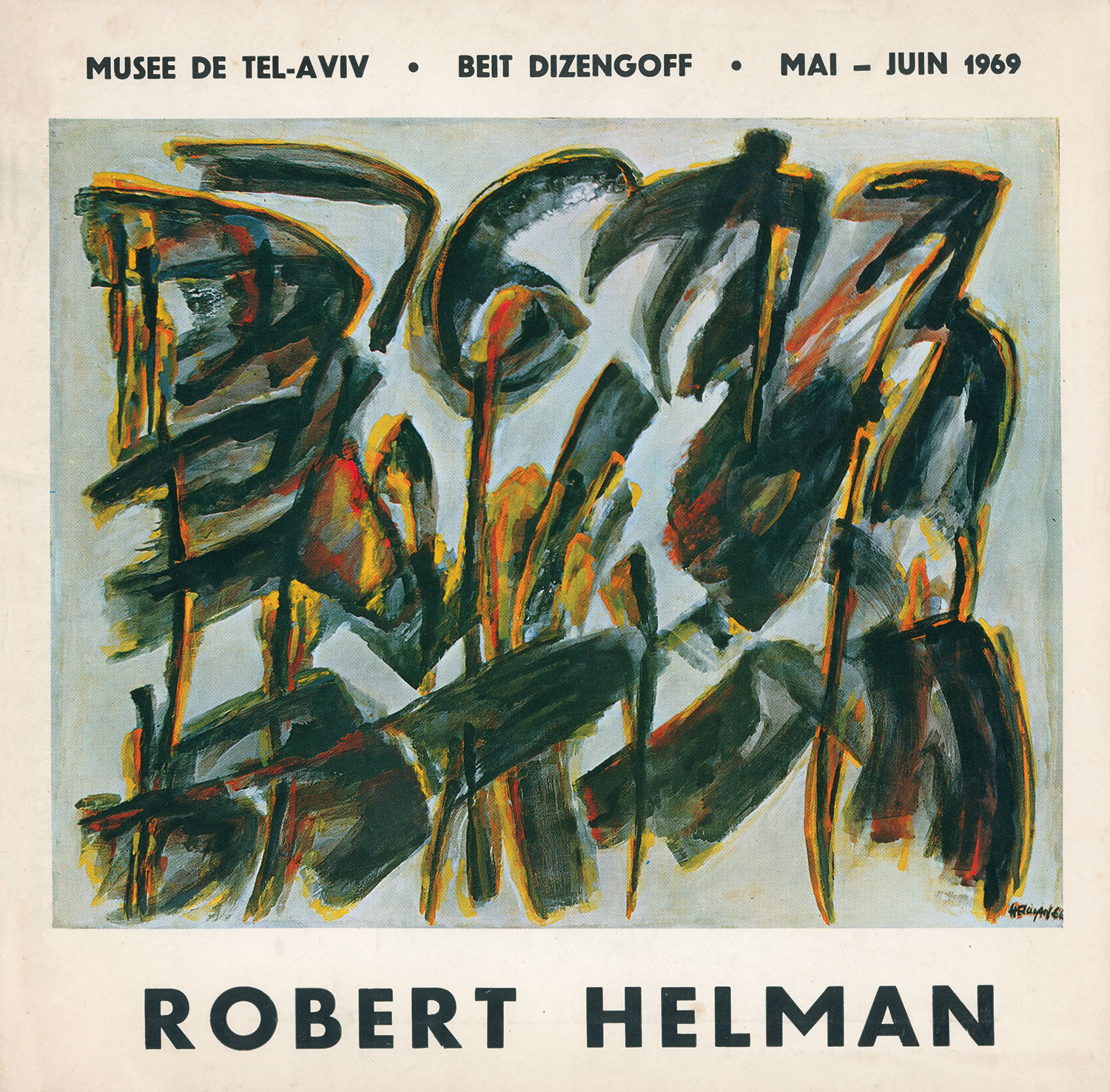

In 1969, the Museum of Modern Art in Tel Aviv dedicated a retrospective exhibition to Helman’s work with a catalogue containing texts by Philippe Soupault, Jacques Lassaigne, Giuseppe Marchiori, Georges Boudaille and Pierre Restany. During this stay in Israel, the artist created a series of tapestries which he exhibited in New York at the Greer Gallery in 1972. Helman created a second series of tapestries in 1973 at the Aubusson tapestry workshop.

In 1975, a third monograph devoted to Helman and written by Max-Pol Fouchet was published by Cercle d’Art. In 1981, the artist met the German gallery owner Wolfgang Gunther who gave him the opportunity to exhibit his work regularly in Germany for many years. In 1983, Robert Helman had his first major retrospective exhibition at the Orangerie de Bagatelle in Paris, organised by Françoise Marquet, curator at the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris.

Robert Helman lost his left eye while opening a bottle of champagne at the age of 73 in 1983. Greatly impaired by the surgical procedures that followed, the artist resumed painting a few months later – once again depicting suns, a theme of hisearly works. In 1987, the painter received the art historian Lydia Harambourg at his studio as she was preparing her Dictionnaire des peintres de l’École de Paris, which was published in 1993.

Photomontage de Jean Louvel, 1982

In 1988, Robert Helman took up permanent residence in his house in Champagne, where he created metal sculptures that were then exhibited at the Galerie Michèle Heyraud and the Galerie La Pochade in Paris. The following year, Helman signed a contract with the Galerie Eterso in Cannes, which bought some of his artworks and showed them alongside works by Olivier Debré, Hans Hartung and Gérard Schneider.

On 9 February 1990, the artist Robert Helman celebrated his 80th birthday at the Fondation Cartier pour l’Art Contemporain at the invitation of the foundation’s director Marie-Claude Beaud. Robert Helman died on 7 November 1990 at his home in Champagne, France.

Jean Delahaye, Dino Abidine, Jean Cocteau, Robert Helman & André Verdet

Galerie Octobon, Saint-Paul-de-Vence, août 1955, Photographe : Jacques Gomot

Jean Cocteau devant une toile de Robert Helman Galerie Octobon, Saint-Paul-de-Vence, août 1955

Photographe : Jacques Gomot

Robert Helman dans son atelier 83 bd du Montparnasse, Paris, 1962

SELECTED COLLECTIONS

Cagnes-sur-Mer (France), Castle Museum

Colmar (France), Unterlinden Museum

Dijon (France), Musée des Beaux-Arts – Granville Donation

Indianapolis (IN), Indianapolis Museum of Art

Jerusalem (Israel), Israel Museum

London (United Kingdom), Tate Modern Gallery

Paris (France), Fonds National d’Art Contemporain

Paris (France), Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris

Paris (France), Musée National d’Art Moderne – Centre Pompidou

Saint-Paul-de-Vence (France), Municipal Museum

Sens (France), Sens Museums

Stuttgart (Germany), Stadtmuseum

Tel Aviv (Israel), Tel Aviv Museum of Art

Troyes (France), Musée d’Art Moderne

Turin (Italy), Galleria Civica d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea

SELECTED EXHIBITIONS

Group exhibition: Bayon, Rutta Block de Rosenstingl, Calderon, E. Castells, J. Colson, M. Fargas, Fret, Gabino, Grandara, Helman, Hubert Vallmitjana, J.O. Jansana, T. Kurimoto, Olive Busquets, Sanjuan, José M. de Sucre, Galerias Reig, Barcelona, 1945

Solo exhibition, Galerias Pictoria, Barcelona, 1945

Solo exhibition, Galerie Berri-Raspail, Paris, 1947

Solo exhibition, Galerie Alsace-Lorraine, Oran (Algeria), 1947

Solo exhibition, Galerie Le Nombre d’Or, Alger (Algeria), 1947

Solo exhibition, Galerie Breteau, Paris, 1948

Group exhibition: Les Six Jours (The Six Days), Atlan, Booumeester, Smadja, Soulages, Bertholle, Beyer, Le Moal, Manessier, Bott, Domínguez, Hartung, Picasso, Guita, Goetz, Loubchansky, Shoffer, Helman, Moisset, Parra, Vanier, Jacobsen, Gilioli, Leleu, Étienne-Martin, Galerie Breteau, Paris, 1948

Solo exhibition, Galerie Colline, Oran (Algeria), 1948

Solo exhibition, Galerie Louis Manteau, Brussels, 1949

Solo exhibition of watercolours, Galerie Mouradian-Valloton, Paris, 1952

Solo exhibition, Incontro con Robert Helman, Galleria Sandri, Venice, 1952

Solo exhibition, Agnès Lefort Gallery, Montreal, 1954

Solo exhibition, Elisabeth Nelson Gallery, Chicago, 1954

11th Salon de Mai, Paris, 1955

Group exhibition, L’École de Paris (The Paris School), Galerie Charpentier, Paris, 1955

Group exhibition: Aïzpiri, Beaulieu, Calmettes, Clavé, Condoy, Cortot, Domínguez Nita Flores, Helman, Galerie 73, Paris, 1955

Solo exhibition, Galerie Octobon, Saint-Paul-de-Vence, 1955

Solo exhibition, Galerie Henri Bénézit, Paris, 1955, 1957

Group exhibition: Atlan, Chapoval, Garbell, Janson, Helman, Lanskoy, Pichette, Tal Coat,

Galerie Henri Bénézit, Paris, 1956-1957

Group exhibition: Henri Bénézit et Éraste Touraou présentent : (Henri Bénézit and Éraste Touraou present:) Atlan, Chapoval, Helman, Lanskoy, Pichette, Tal Coat, Galerie Ex-Libris, Brussels, 1957

Group exhibition: Anthoons, Chapoval, Chavignier, Corneille, Doucet, Garbell, Guitet, Helman, Pichette, Sugaï, Galerie Muratore, Nice, 1957

Group exhibition: Atlan, Chapoval, Garbell, Janson, Pichette, Caillaud, Duault, Helman, Lanskoy, Tal Coat, André Verdet, Galerie Sous-Barri, Saint-Paul-de-Vence, 1957

Group exhibition, Contemporary Jewish Artists of France, Atlan, Chagall, Mané-Katz, Michonze, Zack, Helman, Ben Uri Art Gallery, London, 1957

Solo exhibition, Galleria Apollinaire, Milan, 1958

Solo exhibition, Galleria Blu, Milan, 1958

14th Salon de Mai, Paris, 1958

Solo exhibition, Nicole Gallery, New York, 1958

Solo exhibition of ink works, gouaches and drawings, La Hune, bookshop-gallery, Paris, 1959

Group exhibition, L’École de Paris : cinq critiques désignent sept artistes (The School of Paris: five critics nominate seven artists), Buffet, Pignon, Masson, Istrati, Helman, Galerie Charpentier, Paris, 1959

Group exhibition, French Painting Today, Hartung, Helman, Vieira da Silva, and others, Association of Israel Museums, Bezalel National Museum, Jerusalem, 1960

Group exhibition, Sept peintres de l’École de Paris (Seven painters of the School of Paris) (Adamoff, Helman, Abidine, Arbas, Lan-Bar, Orazi, Klieman), Galerie Pego’s, Montreal, 1960

Solo exhibition, Nicole Gallery, New York, 1960

Touring exhibition across the United Kingdom (the Towner Art Gallery, Eastbourne; the Art Gallery, Southampton; the National Museum of Wales, Cardiff; the Art Gallery, Aberdeen; the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, Glasgow; the Ferens Art Gallery, Kingston-upon-Hull; the City Museum & Art Gallery, Birmingham; the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool) organised by the Arts Council, The Margulies Collection: New Paintings From Paris, 1960-1961

Group exhibition: Bellegarde, Halpern, Helman, Krajcberg, Orazi, Cave-Galerie Jeanne Fillon, Paris, 1961

Solo exhibition, Galerie du XXe siècle, Paris, 1961

Solo exhibition, La Forêt (The Forest), Galleria Blu, Milan, 1961

Solo exhibition, Galerie Jacques Martin, Saint-Paul-de-Vence, 1961

Solo exhibition, Galerie Parti-Pris, Grenoble, 1961

Group exhibition, Exposition des artistes de la galerie (Exhibition of the gallery’s artists): Atlan, Dubuffet, Fautrier, Helman, Lanskoy, Maryan, Messagier, Poliakoff, Rebeyrolle, Riopelle, Tal Coat, Wols, Galerie Beno d’Incelli, Paris, 1962

Group exhibition, La Collezione di un Bambino, Galleria Il Traghetto, Venice, 1962

18th Salon de Mai, Paris, 1962

Solo exhibition, La Forêt (The Forest), Galleria il Canale, Venice, 1962

Solo exhibition, Galleria Il Centro, Naples, 1963

19th Salon de Mai, Paris, 1963

Solo exhibition, Robert Helman, Jardins et Forets (Robert Helman, Gardens and Forests), Casino Du Liban, Beirut, 1963

Solo exhibition, La Forêt (The Forest), Galerie Cavalero, Cannes, 1963

Solo exhibition, Hilt Gallery, Basel, 1963

Group exhibition, Painting and Sculpture Today, Indianapolis Museum of Art, Indianapolis, 1964

Solo exhibition, Galerie Lutz & Meyer, Stuttgart, 1964

Group exhibition, Caillaud, Chavignier, Clavé, Dumitresco, Helman, Istrati, Galerie Beno d’Incelli, Paris, 1964

Solo exhibition, La Sala Gaspar, Barcelona, 1964

Solo exhibitions, Galerie Beno d’Incelli, Paris, 1965, 1968, 1972

Solo exhibition, Stewart-Verde Gallery, San Francisco, 1966

Solo exhibition, Municipal Museum, Saint-Paul-de-Vence, 1967

Group exhibition, Robert Helman and Marcello Avenalli, Galleria Santa Maria, Rome, 1967

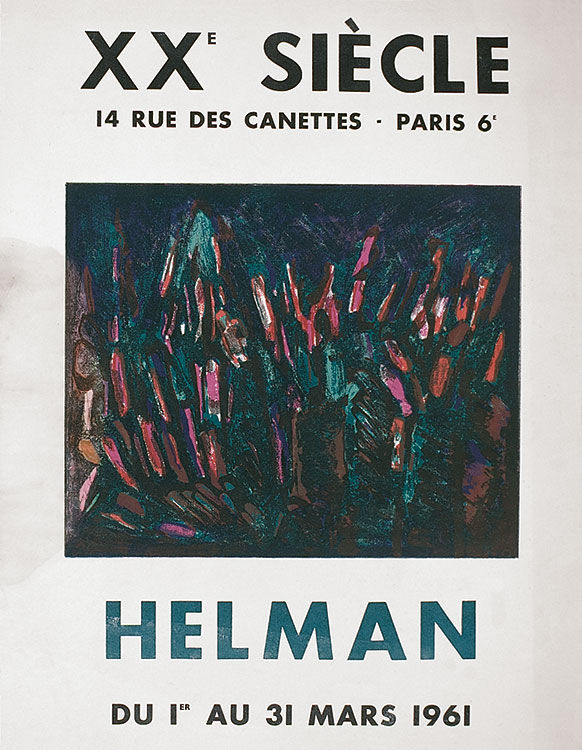

Affiche de l’exposition Helman

Galerie XXe siècle, Paris, 1961

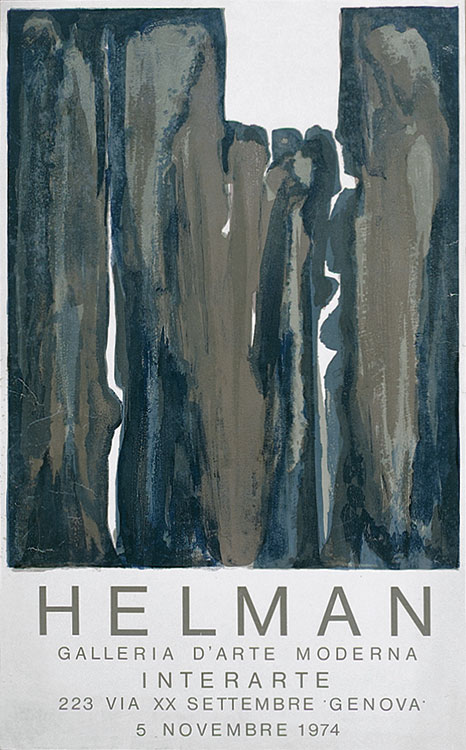

Affiche de l’exposition Helman

Galleria d’arte moderna, Gênes, 1974

Solo exhibition, L’Entracte, Lausanne (Switzerland), 1969

Solo exhibition, Tel Aviv Museum of Art, Tel Aviv, 1969

Group Exhibition, Présence européenne, Galleria La Bussola, Turin, 1971

Group exhibition, Paintings and tapestries by Robert Helman; sculpture in marble by Nardo Dunchi, Allan Rich Gallery, New York et Greer Gallery, New York, 1972

Solo exhibition, Galleria Procolo, Castellana Grotte (Italy), 1972

Solo exhibition, Peintures et tapisseries sur le thème de la forêt : 1957-1972 (Paintings and tapestries on the theme of the forest: 1957-1972), Castle Museum, Cagnes-sur-Mer, 1973

Solo exhibition, Galleria La Seggiola, Salerno (Italy), 1973

Solo exhibition, Robert Helman : Peintures et Gouaches (Robert Helman: Paintings and Gouaches), Galerie Albert Verbeke, Paris, 1974

Solo exhibition, Robert Helman : Tapisseries et Écorces (Robert Helman: Tapestries and Bark Paper Works), Galerie Jacques Verrière, Paris, 1974

Solo exhibition, Kar Gallery, Toronto, 1974

Solo exhibition, Galleria Interarte, Genoa, 1974

Solo exhibition, Musée de l’Outil, Troyes, 1975

Solo exhibition, Galerie Albert Verbeke, Paris, 1975

Solo exhibition, Galerie Frédéric Gollong, Saint-Paul-de-Vence, 1975

Solo exhibition of engravings and gouaches, Artcurial, Paris, 1977

Group exhibition, Meubles Tableaux, Centre National d’Art Contemporain, Centre Pompidou, Paris, 1977

Solo exhibition, Gordon Gallery, Tel Aviv, 1977

Solo exhibition, Galleria Guglielmo Tell, Chiasso (Switzerland), 1977

Group exhibition, Le paysage intérieur, aujourd’hui, Château de Vesvres, 1978

Group exhibition, Jewish Art: paintings and sculptures by 20th-century Jewish artists from the French and British schools (Atlan, Zadkine, Soutine, Modigliani, Chagall, Helman), Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, Glasgow, 1979

Solo exhibition, Figure humaine – peintures et écorces (Human Figure – paintings and bark paper works), Galerie Bellint, Paris, 1979

Solo exhibition, Château de Mont-Saint-Jean, 1980

Solo exhibition, Genèses, Galerias Rayuela, Madrid, 1981

Solo exhibition, Limmer Gallery, Freiburg (Germany), 1981, 1984, 1985, 1987, 1989

Solo exhibition, Quatre Éléments, Siete Siete Gallery, Caracas, 1981

Solo exhibition, Greer Gallery, New York, 1981

Solo exhibition, Becher Gallery, Wuppertal (Germany), 1982, 1985

Retrospective solo exhibition, Helman – Peintures 1943-1983, Orangerie de Bagatelle, Paris, 1983

Solo exhibition, Galerie Michèle Heyraud – Nadine Bresson, Paris, 1983, 1988

Group exhibition, Matisse, Picasso, Chagall, Fautrier, Bellmer, Dali, Karskaya, Fini, Helman,

Scherer Gallery, Freiburg (Germany), 1983

Group exhibition, Charles Estienne & l’Art à Paris 1945-1966, Centre National des Arts Plastiques, Paris, 1984

Group exhibition, Aspect de l’art en France de 1950 à 1980, collection of Christie and Lionel

Cavalero, Musée Ingres, Montauban, 1985

Solo exhibition, Robert Helman, Landscapes of Genesis, Mayanot Gallery, Jerusalem, 1986

Solo exhibition, Galerie La Pochade, Paris, 1986, 1987, 1988

Group exhibition, Accrochage 50, Galerie Nickel-Odéon, Paris, 1986

Solo exhibition, La Genèse de la Lumière (The Genesis of Light), Palais des Congrès, Megève, 1988

Group exhibition, D’hier à aujourd’hui : Arnal, Doucet, Debré, Hartung, Helman, Schneider, Galerie Eterso, Cannes, 1989

Solo exhibition, Helman – 50 ans de peinture, Galerie Eterso, Cannes, 1990

Solo exhibition, Hommage à Robert Helman, Galerie Duras-Martine Queval, Paris; Galerie Valsyra, Lausanne, Montreux; Galerie Eterso, Cannes, 1991

Retrospective solo exhibition, Helman 1910-1990, peintures et sculptures, Musée d’Art Moderne, Troyes, 1994

Solo exhibition, Galerie Nicolas Deman, Paris, 2000

Solo exhibition, Robert Helman – Paysages imaginaires de la Genèse (Robert Helman – Imaginary Landscapes of Genesis), Musée d’Unterlinden, Colmar (France), 2007

Solo exhibition, Galerie 53, Paris, 2007

Solo exhibition, Robert Helman, Orangerie, Sens Museums, Sens, 2010

Solo exhibition, Galerie 53, Paris, 2010

Group exhibition, Dmitrienko, Helman, Lindström, Maria Manton, Vieira da Silva and others, Art Elysées, Paris, 2010

Group exhibition, Gris … Ouverture sur la couleur, Asse, Bitran, Helman, Lindström, Arpad Szenes, Vieira da Silva, and others, Galerie 53, Paris, 2010

Group exhibition, La lettre secrète, Helman, Karskaya, Vieira da Silva, Jan Voss, and others, Galerie de Beaune, Paris, 2015

Group exhibition, Orient Express…de Paris à Istanbul, Abidine, Dumitresco, Hantai, Helman, Herold, Vasarely, Galerie Courtaigne, Paris 2018

Group exhibition, Le Paysage imaginaire, Huguette Arthur Bertrand – Robert Helman, Galerie Diane de Polignac, Paris, December 6, 2022-January 8, 2023

Solo exhibition, Robert Helman, La Genèse – Éternité en devenir, Galerie Diane de Polignac, Paris, May 11-June 10, 2023

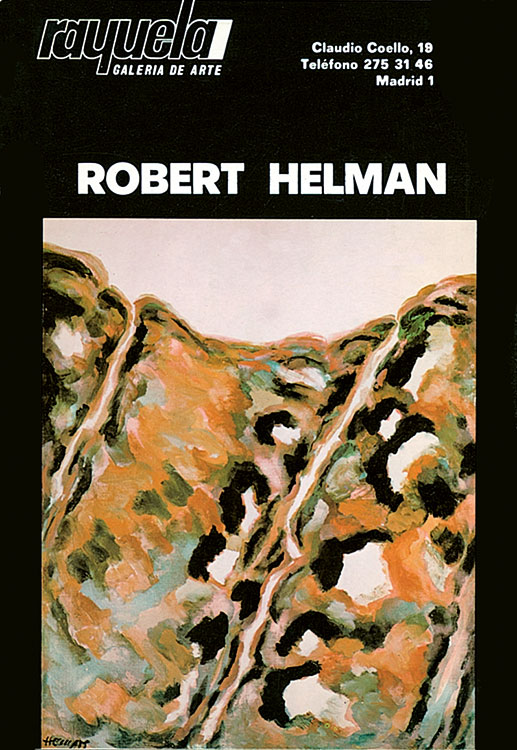

Affiche de l’exposition Robert Helman

Galerias Rayuela, Madrid, 1981

Affiche de l’exposition Robert Helman Paysages imaginaires de la Genèse

Musée Unterlinden, Colmar, 2007

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

Jean Bouret, Helman, Paris, Les Gémeaux, “Les artistes du temps présent” coll., 1951

Jean Cassou, Les Peintres témoins de leur temps (Painters as Witnesses of their Time), Paris, Musée d’Art Moderne, 1953

Raymond Cogniat, L’Histoire de la peinture (The History of Painting), Paris, Fernand Nathan, 1955

Raymond Nacenta, École de Paris, son histoire, son époque (The School of Paris, its history, its era), Neuchâtel, Ides et Calendes, 1958

Pierre Restany, Lyrisme et Abstraction (Lyricism and Abstraction), Milan, Apollinaire, 1958

Philippe Soupault, Helman, Paris, Georges Fall, “Le Musée de Poche” coll., 1959

André Verdet, Forêts de Helman (Helman’s Forests), Saint-Paul-de-Vence, Parler, 1961

Georges Boudaille, Denys Chevalier, Marie-Henriette Foix, Alain Gheerbrant, Giuseppe Marchiori, “Helman”, Parler journal, Paris, no. 15, spring 1963

Giuseppe Marchiori, Helman, Paris, Impriludes-Bernard Lucas, Paris, 1965

André Verdet, Vers une République du Soleil (Towards a Republic of the Sun), Paris, Jean Oswald, 1968

Max-Pol Fouchet, Helman, Paris, Cercle d’Art, 1975

Ronald Alley, Catalogue of the Tate Gallery’s Collection of Modern Art Other Than Works by British Artists, London, Tate Gallery and Sotheby Parke-Bernet, 1981

Françoise Armengaud, Titres, interview with Robert Helman, 24 March 1986, Paris, Méridiens Klincksieck, 1988

Lydia Harambourg, L’École de Paris, 1945-1965, Dictionnaire des peintres (The School of Paris, 1945-1965, Dictionary of painters), Neuchâtel, Ides et Calendes, 1993

Emmanuel Bénézit, Dictionnaire des peintres, sculpteurs, dessinateurs et graveurs (Dictionary of Painters, Sculptors, Drawers and Engravers), Paris, Gründ, 2006

Lydia Harambourg, Robert Helman, Musée Unterlinden, Paris, Somogy, 2007

Lydia Harambourg, Helman, Paris, Cercle d’Art, “Découvrons l’art du XXème siècle” coll., 2010

Clotilde Scordia, Robert Helman, La Genèse, Éternité en devenir, exhibition catalogue, Paris, Galerie Diane de Polignac, 2023

Couverture de la monographie Robert Helman par Philippe Soupault, Paris, Georges Fall, coll. « Le musée de poche », 1959

Couverture du catalogue de la rétrospective Robert Helman, Musée d’Art moderne de Tel-Aviv, mai-juin 1969

Robert Helman dans son atelier, 45 rue Boissonnade, Paris, 1981

The Diane de Polignac Gallery thanks Henri and Isabelle Helman for making this beautiful project of exhibition and

publication possible. The Diane de Polignac Gallery would also like to thank Clotilde Scordia for her collaboration and invaluable assistance.

Robert Helman

Genesis

Eternity on the move

Exhibition from May 11 to June 10, 2023

Diane de Polignac Gallery

2 bis, rue de Gribeauval, Paris

www.dianedepolignac.com

Translation: Lucy Johnston

Graphic design: Diane de Polignac Gallery

ISBN: 978-2-9584349-3-9

© Diane de Polignac Gallery, Paris, May 2023

Texts are author’s property

© ADAGP, Paris 2023 for the works of Robert Helman

Reserved rights