THE 1940s

Exhibition March – April 2022

THE 1940s

When surrealist practices enabled abstract art to flourish

The artists Serge Charchoune (1888-1975), Henri Goetz (1909-1989), Marie Raymond (1908-1989) and Gérard Schneider (1896-1986) were closely associated with each other from the end of the 1930s to the 1940s and their works were exhibited together on the Parisian art scene. All four painters were influenced by Surrealism and retained formalistic traces of the movement in their work. This transition from the influence of a fundamentally figurative movement to the revival of abstract art in the 1940s represents a major turning point—a period which we have chosen to highlight in this exhibition.

THE SURREALIST ROOTS OF ABSTRACT ART

Surrealism is considered to have emerged in 1924 when André Breton published the first Surrealist Manifesto. In the manifesto, Breton defined the movement as “Pure psychic automatism, by which one proposes to express, either verbally, in writing, or by any other manner, the real functioning of thought.” Surrealism encouraged artists and poets to free their unconscious and to create as spontaneously as possible. Automatism would be applied to the creation of visual and literary works through exquisite corpses, group collages and the creation of tarot cards, for example. These surrealist strategies would enable some artists to take steps towards abstraction in their work.

It is important to note, however, that none of the great surrealist artists ‘knighted’ by André Breton were abstract painters. In the works of Victor Brauner, Salvador Dali, Giorgio de Chirico, Óscar Domínguez, Max Ernst, Wifredo Lam, René Magritte, André Masson, Roberto Matta and Yves Tanguy, surrealism took the form of a fundamentally figurative movement. These painters represented reality: a reality of the mind, an inner universe. Any move to abstraction was a break with surrealism.

Oscar DOMINGUEZ

Lion-bicyclette – 1937 – Décalcomanie, gouache au pochoir sur papier – 15,8 x 22,3 cm.

Centre Pompidou, Paris

En haut : Paul Chardourne, Tristan Tzara, Philippe Soupalt, Serge Charchoune

En bas : Man Ray, Paul luard, Jacques Rigaut, Mme Soupault, Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes

Collage de Man Ray, 1922 – Centre Pompidou, Paris

The novelist Raymond Queneau described the movement as a “means of total liberation of the mind. It is a cry of the mind turning back on itself. Every true follower of the surrealist revolution is bound to think that the surrealist movement is not a movement in the abstract, and especially a certain poetic kind of abstract, which is hateful in the highest degree, but is really capable of changing something in the minds.” [1]

Some painters who were close to the movement would come to understand the artistic liberation that it allowed and, as a result, become full-fledged abstract painters. Such artists included not only Serge Charchoune, Henri Goetz, Marie Raymond and Gérard Schneider, but also Joseph Sima, Christine Boumeester and Marcelle Loubchansky, among others. The art critic Éric de Chassey wrote: “Artists used surrealism by reactivating its creative and destabilising potential without worrying about whether they were conforming to the principles defined by André Breton from 1924 onwards.” [2] As such, surrealism came to exist in a different way. A way of thinking, living and expressing oneself above all, and not just an organised movement, it would influence a large number of artists who painted, sculpted, wrote, and more. André Breton himself stated that “Surrealism survived ‘diffused’ in such or such a person.” He recognised that some artists “sailed alone” like Jacques Prévert and Joan Miró. On the subject, the artist Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes wrote: “What remains is the rage to create. The last resource of the inner world. A very beautiful passion there too. To create from scratch a new world of forms, colours and sounds. The main thrust of today’s artistic sensibility is abstraction, or at least the abstract exercise of forms, colours and sounds, stripped of all ties to nature and existing in themselves.” [3] Automatism was thus absorbed and assimilated, without contradicting abstract tendencies.

Over the course of the 19th and 20th centuries, artists gradually freed themselves from the need to resemble reality. Photography in particular allowed this new autonomy to develop, and then impressionism moved away from the subject itself to focus on the effects of light.

1 – Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes, Déjà jadis ou du mouvement Dada à l’espace abstrait, Paris, Les belles lettres, 2016

2 -Éric de Chassey, “Le surréalisme dans l’art états-uniens, de l’entre-deux-guerres à l’abstraction excentrique (1930-1970)”, exhibition catalogue for Le Surréalisme dans l’art américain [“Surrealism in American art”], the City of Marseille, 2021

3 – Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes, Déjà jadis ou du mouvement Dada à l’espace abstrait, Paris, Les Belles Lettres, 2016

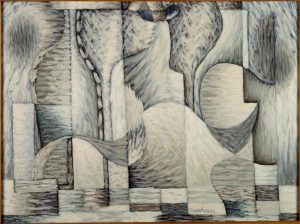

Christine BOUMEESTER

Sans titre – 1938/1939 – Pastel sur papier – 26 x 37 cm.

Musée Goetz-Boumeester, Villefranche-sur-Mer

Henri Goetz et Christine Boumeester

Photo: Hans Hartung

The fauvists then devoted themselves to colour, the subject only existing as a base. Then cubism deconstructed the subject through form, before the dada and surrealist movements liberated the unconscious, the subjective and the spontaneous, ushering in the transition to pure abstraction.

Some major artists had been pioneers of the abstract movement at the beginning of the 20th century: Hilma af Klint, Vassily Kandinsky, Kasimir Malevich, Piet Mondrian and František Kupka, among others. How did surrealism bring about a renaissance of abstract art in the 1930s? In Paris, the 1930s represented the apotheosis of the glory of Picasso, Matisse and Bonnard. The pioneers of abstraction had almost been forgotten. Paul Klee died in Locarno in 1940, followed by Robert Delaunay in Montpellier in 1941. Piet Mondrian left Paris in 1938 and died in New York in 1944. Vassily Kandinsky died in the same year in Neuilly-sur-Seine, just west of Paris. The first generation of abstract artists was therefore lost during the war. It is interesting to note what Mondrian once claimed to Peggy Guggenheim: “I feel closer to the surrealists, in spirit and except for the literary side, than to any other kind of painting.”

FROM FIGURATIVE TO ABSTRACT

The Russian painter Serge Charchoune, the doyen of our exhibition, discovered the dada movement in Barcelona, where he took refuge in 1914. It was in the Spanish city that Charchoune met Francis Picabia, who introduced him to Tristan Tzara on his return to Paris in 1920. Charchoune thus joined the dada movement and was invited to participate in the group’s meetings and events. From the 1920s onwards, Serge Charchoune was thus very close to the artists and writers that made up the dada movement—figures who would become leading proponents of surrealism. Influenced by cubism and the dada movement, Charchoune presented his first abstract paintings—which he described as “ornamental”—in 1916 at the Josef Dalmau Gallery in Barcelona. Throughout his life, Charchoune would move back and forth between periods of pure abstraction and more figurative periods. It was in 1954 that Serge Charchoune met the painter Nicolas de Staël. The latter, who admired the artist and owned one of his paintings, described Charchoune as “the greatest among us”.

As for Henri Goetz, it was in 1930 that the American arrived in Paris, where he would discover surrealist painting. The following year, he married the painter Christine Boumeester, whom he had met at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière. From 1935, the couple became closely involved with Hans Hartung and Gérard Schneider.

Vassily KANDINSKY

Sans titre – vers 1930 – Encre de Chine et aquarelle sur papier – 36,5 x 37,5 cm.

Centre Pompidou, Paris

Gérard SCHNEIDER

Paysage imaginiare – 1937/39 – Huile sur toile – 54 x 65 cm.

Collection privée, France

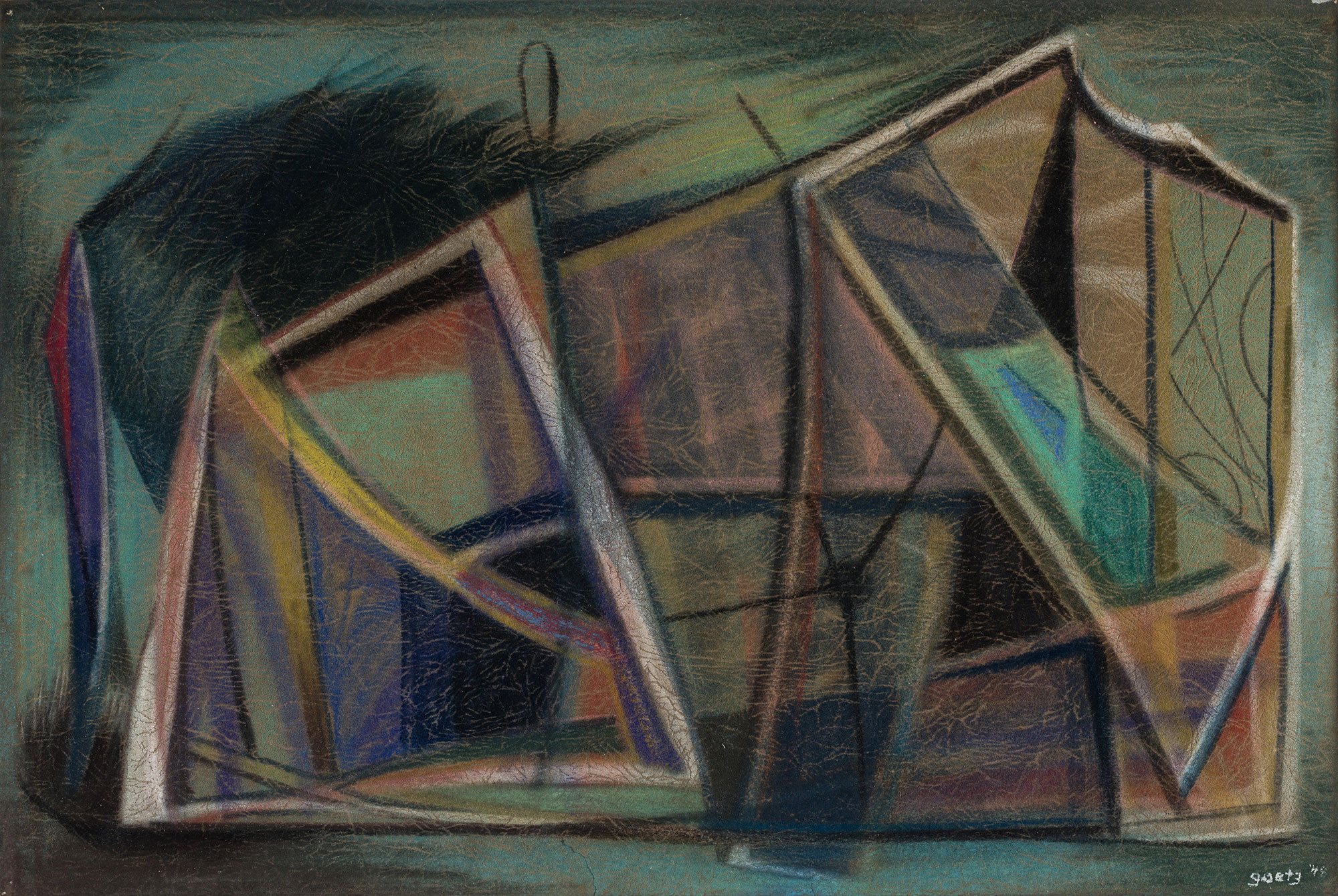

It was at this time that Goetz’s work shifted to a non-figurative style of painting with a surrealist slant. In the artist’s own words: “I believed I could create forms wherein my unconscious would join those of others. This approach was not unrelated to that of the surrealists but it was carried out in a universe of forms that were abstract for me, and yet evocative of known objects, sometimes organic. This resemblance hardly interested me, which distanced me from the surrealists. The space of my paintings resembled that of classical works. I was not considered an abstract artist and yet I felt closer to them.” [4] In 1942, the Goetz-Boumeester couple took refuge in the South of France, where they spent time with Jean Arp, Nicolas de Staël, Marie Raymond and the Picabias.

In Nice in 1932, Marie Raymond became close to Nicolas de Staël. At the beginning of the war, she began to paint Paysages imaginaires (1941-1944) inspired by her walks in the hinterland of Nice, landscapes that had “the spontaneous forms of surrealist painting”. It was at this time that she met the painter Jean Arp, whose biomorphic forms can be found reflected in her Paysages imaginaires. She was also greatly influenced by the works of André Masson. At the end of the war, Raymond emerged from her post-surrealist period and chose to pursue the abstract once and for all. The wife of the Dutch painter Fred Klein, Raymond naturally befriended Henri Goetz, who was married to the Dutch painter Christine Boumeester. The Raymond-Kleins were also close to another Dutch painter—Piet Mondrian—with whom they shared a studio. Marie Raymond recalled: “It was like a family with many brothers on the same side who met up and enjoyed themselves in endless conversations.”

From the 1920s to the mid-1930s, Gérard Schneider painted figurative works—“imaginary landscapes” inspired by surrealism. Writing about Schneider, the art critic Michel Ragon noted: “the role that surrealism gives to the unconscious, to dreams, to automatic writing, interests him. While he did not join the surrealist group, it was still the only brotherhood to which he was close in 1937.” [5]

4 – Mes démarches, a handwritten letter by Goetz dated 10 June 1975, reproduced in a brochure published by the Galerie La Pochade for a touring exhibition that travelled around cultural centres.

5 – Michel Ragon, Schneider, Angers, Expressions contemporaines, 1998

Hans HARTUNG

Sans titre – 1935 – Crayon gras, aquarelle et encre de Chine sur papier – 62,7 x 44,3 cm.

Centre Pompidou, Paris

Marie-Thérèse Gonzalez, Fred Klein, Roberta Gonzalez, Gérard Schneider, Marie Raymond, Colette et Pierre Soulages, Yves Klein et Pilar Gonzalez.Repas de Noël, 1948 – Christmas dinner, 1948

Photo: Hans Hartung – Fondation Hans Hartung

Gérard Schneider was close to the Surrealist painter Óscar Domínguez and the poets Paul Éluard and Georges Hugnet. Schneider produced paintings inspired by surrealism and also wrote poems, some of which were published in the journal La Main à la plume (1941-1944), a collective surrealist publication founded by Christine Boumeester and Henri Goetz, among others. In 1942, Gérard Schneider exhibited his abstract works with the “Allianz” group, centred around the artist Jean Arp, at the Kunsthalle in Bern.

EXHIBITIONS, ENCOUNTERS & FRIENDSHIP

Our four artists were close to dadaist and surrealist authors and artists and used the strategies of the unconscious, automatism and spontaneity to enable their transitions to abstraction. Furthermore, we have chosen to show these four artists in particular because they knew each other and their works were exhibited together during their lifetimes.

The Galerie Jeanne Bucher, for example, showed the works of Marie Raymond, Henri Goetz and Serge Charchoune. From 1946, the Galerie Colette Allendy represented Marie Raymond, Gérard Schneider and Henri Goetz at the same time. The exhibition Peinture Abstraite: Dewasne Deyrolle Marie Raymond Hartung Schneider, which took place the same year at the Galerie Denise René, is also worth noting. The same gallery also presented works by Serge Charchoune in 1963. The four artists also had friends in common, such as Nicolas de Staël, Jean Arp and Francis Picabia.

Marie Raymond, who was also an art critic, published numerous articles, including for the Dutch journal Kunst en Kultuur, for which she worked as the Paris correspondent from 1939 to 1958. She wrote, for example, an article on an exhibition of Gérard Schneider’s work at the Galerie Lydia Conti and an article on Henri Goetz at the Galerie des Deux-îles in 1949.

One of the most important events that cemented the bond between these four artists was the 12th Salon des Surindépendants in 1945 (20 Oct-13 Nov 1945, Parc des Expositions – Porte de Versailles, Paris).

Jean ARP

Papier déchiré – 1932 – Papiers déchirés et collés sur papier – 14 x 14 cm.

Centre Pompidou, Paris

Invitation pour l’exposition Peintures abstraites : Dewasne, Deyrolle, Marie Raymond, Hartung, Schneider, Galerie Denise René, Paris, France, 26 février–20 mars 1946.

© Archives Marie Raymond, Paris.

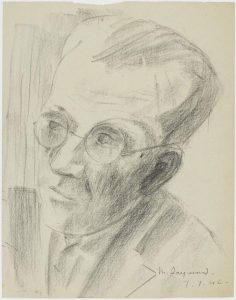

). It was the first major post-war exhibition of abstract art, bringing together not only abstract works but also artists that had until then been scattered by the world conflict. Such painters were able to meet in person and discuss their work. French nationals and foreigners in Paris exchanged ideas and forged friendships. It was the first time that the works of Serge Charchoune, Marie Raymond and Gérard Schneider were exhibited together. When Marie Raymond wrote about the Salon in the Dutch journal Kunst en Kultuur, she chose to illustrate her article with a work by Serge Charchoune. In addition, she drew his portrait the following year (the portrait is now housed at the Centre Pompidou, Paris). Henri Goetz, who met Marie Raymond at the exhibition, also made a portrait of Charchoune.

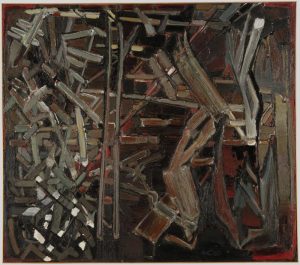

At this edition of the Salon des Surindépendants, Gérard Schneider exhibited a painting entitled Les Pendus—a figurative title meaning “the hanged”, which provides a key to reading the abstract composition. On the subject, the artist wrote: “The new possibilities of abstract painting are oriented towards an expressive and dramatic content of the creation of forms. In abstraction, painting finds what is essential for its technical and explosive purpose by excluding unnecessary external elements.”[6]

With the 100th anniversary of Surrealism approaching, we realise how profoundly its methods have affected 20th-century art. Some figurative artists who came close to the movement without actually joining it are also worth mentioning, such as Louise Bourgeois, Alberto Giacometti, Dora Maar and Jacques Prévert. Surrealism also crossed the Atlantic during the Second World War and contributed to the emergence of abstract expressionism. The influence that André Masson had on Jackson Pollock is just one of many examples. René Magritte’s work with imagery can be found reflected in pop art by Andy Warhol, while Jasper Johns was inspired by Marcel Duchamp’s misappropriation of objects. Surrealism, a fundamentally figurative movement, thus opened the door to abstract art because its automatic approach served a form of painting that was “devoid of representation” but “as rich as nature”. [7]

6 – ibid

7 – Robert Motherwell in Max Kozloff’s “An Interview with Robert Motherwell”, Artforum, vol. IV, no. 1, September 1965, p. 34

André MASSON

Dessin automatique – 1925 – 1926 – Encre de Chine sur papier – 31,5 x 24,5 cm.

Centre Pompidou, Paris

Marie RAYMOND

Portrait de Serge Charchoune, 1946

Fusain sur papier

30,5 x 24 cm.

Centre Pompidou, Paris

Henri GOETZ

Portrait de Serge Charchoune, 1945

Encre brune sur traits à la mine graphite sur papier

28 x 18,7 cm.

Centre Pompidou, Paris

ŒUVRES EXPOSÉES

SERGE CHARCHOUNE (1888-1975)

Nature-morte aux olives – 1942

Oil on cardboard

27 x 35 cm / 10.6 x 13.7 in.

Signed and dated “Charchoune 42” lower right

Serge CHARCHOUNE

Nature-morte au verre – 1941

Oil on cardboard laid down on canvas – 19,6 x 14,2 cm

Centre Pompidou – Paris

Composition à la fourchette – 1942

Oil on cardboard

27 x 35 cm. – 10.6 x 13.7 in.

Signed and dated Charchoune “VI 42” lower right

Amédée OZENFANT

Nature-morte puriste – 1921

Huile sur toile – Oil on canvas – 60 x 73 cm.

Musée d’art moderne et contemporain de Saint-Étienne Métropole

Composition géométrique – 1943

Oil on pannel

50 x 73 cm. – 19.6 x 28.7 in.

Signed and dated “Charchoune 43” lower right

Les chemins de l’invisible – 1947

Oil on canvas

38 x 55 cm. – 14.9 x 21.6 in.

Signed “Charchoune” lower right

Serge CHARCHOUNE

Nature-morte à la cruche – 1941

Huile sur toile – Oil on canvas – 60,4 x 81 cm.

Centre Pompidou – Paris

HENRI GOETZ (1909-1989)

Untitled – 1945

Oil on pannel

37,5 x 46 cm – 14.7 x 18.1 in.

Signed “goetz ” lower right

Salvador DALI

Dormeuse, cheval, lion invisibles – 1930

Huile sur toile – Oil on canvas – 50,2 x 65,2 cm.

Centre Pompidou – Paris

Untitled – 1946

Oil on pannel

44,5 x 53,5 cm. – 17.5 x 21.1 in.

Signed and dated “goetz 46 ” lower right

Alberto MAGNELLI

Chemin coloré – 1947

Huile sur toile – Oil on canvas – 81 x 100 cm.

Musée d’art moderne et contemporain de Saint-Étienne Métropole

Unstitled – 1948

Pastel on paper

33 x 50 cm. – 13 x 19.7 in.

Signed and dated “goetz 48” lower right

Untitled – 1949

Oil on pannel

81 x 65 cm. – 31.9 x 25.6 in.

Signed and dated “goetz 49 ” lower right

Nicolas DE STAËL

La Vie dure – 1946

Huile sur toile – Oil on canvas – 142 x 161 cm.

Centre Pompidou – Paris

MARIE RAYMOND (1908-1989)

Ou prise de conscience des choses elles-mêmes – 1944

Oil on canvas

32,5 x 41 cm. – 12.8 x 16.1 in.

Titled and signed “ou prise de conscience des choses elles-mêmes M.Raymond” lower right

Signed “M. Raymond” on the reverse

Jean ARP

Groupe méditerranéen – 1941-1965

Plâtre – plaster – 78 x 92 x 50 cm

Centre Pompidou – Paris

GÉRARD SCHNEIDER (1896-1986)

Untitled – c. 1942

Oil on canvas

60 x 73 cm. – 23,6 x 28,7 in.

Signed “Schneider” lower right and upper left

Oscar DOMÍNGUEZ

La Couturiére – 1943

Huile sur toile – Oil on canvas – 72 x 49 cm.

National Gallery of Victoria – Melbourne

Opus 266 – 1944

Oil on wood panel

97 x 130 cm. – 38,1 x 51,1 in.

Signed “Schneider” lower right. Titled “Opus 266” on reverse

LES ANNÉES 1940

EXPOSITION: mars – avril 2022

EXHIBITION: March – April 2022

Galerie Diane de Polignac

2 bis, rue de Gribeauval – 75007 Paris

www.dianedepolignac.com

Textes – texts: Mathilde Gubanski

Traduction – translation: Lucy Johnston

© Œuvres : ADAGP, Paris, 2022

Photographies des oeuvres : Droits réservés

© Artworks: ADAGP, Paris, 2022

Photographs of the works: Reserved rights

© Galerie Diane de Polignac, 2022