Five women – Five artistic visions

MARCH 8 – APRIL 16. 2021

Women in Abstract Art: Five Women – Five Artistic Visions

This exhibition intends to show women’s contributions to abstract painting by presenting a selection of five artists: Marie Raymond (1908– 1989), Huguette Arthur Bertrand (1920–2005), Pierrette Bloch (1928–2017), Roswitha Doerig (1929–2017) and Loïs Frederick (1930–2013). These five artists constitute neither a school nor a movement, representing instead five different forms of abstraction, five hard-won freedoms.

Huguette Arthur Bertrand created a body of work characterised by a gestural, exalted form of abstraction. Pierrette Bloch is known for an abstract style defined by repetition and her economic use of materials. Roswitha Doerig, on the other hand, wanted to “step outside the box”, expressing herself through the monumental. Loïs Frederick was a virtuoso colourist painter; colour was both her subject and her medium. Marie Raymond, who Pierre Restany called an “organist of light”, offered us a radiant, sun-drenched vision of painting.

Despite their differences, these five women artists all share a common sense of the sacrifice and struggle necessary to succeed in a man’s world. Huguette Arthur Bertrand was the only woman artist to become part of the group of friends close to the art critic Michel Ragon. Huguette Arthur Bertrand never married or had children, choosing instead to “live like a man” and to devote herself solely to her art. Pierrette Bloch regularly visited the studio of Henri Goetz, who introduced her to Pierre Soulages. Throughout her career, Pierrette Bloch struggled to come out of the shadows of this master of black. Roswitha Doerig came from a Swiss canton where women get the right to vote in 1990: she would defend this cause with passion as she fought to establish herself as a woman artist. Loïs Frederick married the great pioneer of the Lyrical Abstraction movement, Gérard Schneider. Choosing to devote herself to the promotion of her husband’s work, she sacrificed the representation of her own work as a result. Marie Raymond sensed early on that her son would have an exceptional career. A mother above all else, she decided to support her son Yves Klein and to use her resources and contacts in the art world to promote works of art created by members of the Nouveau Réalisme movement. As such, the five women artists we have chosen to exhibit are connected by a sense of self-sacrifice.

Our commitment to presenting these five artists stems from a desire to highlight the work of women unjustly obscured from the history of abstraction. Women artists were not unusual in the second half of the 20th century—they are just less represented. This is due not to a lack of production but a lack of promotion. Christine Macel, chief curator at the Centre Pompidou, confirms: “It must be acknowledged that the majority of exhibitions devoted to the history of abstract art have minimised the fundamental role played by women in the development of its various forms and expressions”.

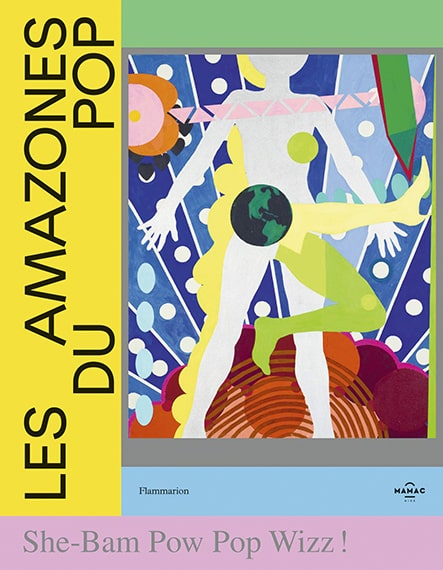

This issue is not unique to a specific time or place and continues to permeate society and the creative realm today. It is not, therefore, out of step with the times to present an exhibition dedicated to women artists. Other notable examples include the exhibition Femmes années 50. Au fil de l’abstraction, peinture et sculpture at the Musée Soulages in Rodez, France, in 2020, She- Bam Pow Pop Wizz ! Les Amazones du Pop at MAMAC in Nice, France (October 2020 – March 2021), and the exhibition Elles font l’abstraction at the Centre Pompidou in Paris in the spring of 2021.

In keeping with the spirit of these events, our exhibition presents five women artists’ different forms of pictorial expression and the contributions they have made to abstraction.

Mathilde Gubanski

February 2021

WOMEN IN ART

From 1945 to today

In this exhibition, we have chosen to present five women artists: Marie Raymond (1908–1989), Huguette Arthur Bertrand (1920–2005), Pierrette Bloch (1928- 2017), Roswitha Doerig (1929–2017) and Loïs Frederick (1930–2013). All five artists primarily lived and worked in Paris. The works of art presented at the gallery span a period ranging from 1944 to the 2000s.

To better understand the works in question, it is essential to explore the wider social and artistic context in which they were produced. As such, we have focused our analysis on France and the second half of the 20th century, with the aim of examining the evolving position of women in the art world within this context. We will look at what was happening in institutions and galleries, as well as the practices of the artists we have selected and how their chosen media constituted conscious choices that have earned them a place in the history of art.

PARIS & THE POST- WAR PERIOD

The post-war period in France began with a major breakthrough: the right to vote, which was granted to women in 1944. Two years later, in 1946, the United Nations created the Commission on the Status of Women. Looking at this period, we cannot neglect to mention the existentialist and feminist essay The Second Sex written by Simone de Beauvoir. Published in 1949, the work caused a major stir as soon as it was released. Another essential element of the post-war landscape was the 1965 French law giving women the right to open a bank account in their own name and to work without their husband’s consent. These advances in women’s rights paved the way for a debate about the representation of women in the art world.

GALLERY OWNERS

In such a climate, post-war Paris was home to numerous galleries that were opened by women. Notable examples included galleries opened by Denise René in 1944, Nina Dausset in 1945, Colette Allendy in 1946, Lydia Conti and Dina Vierny in 1947, Florence Bank (the Galerie des Deux-Iles) in 1948, Suzanne de Coninck (the Galerie de Beaune) in 1949, as well as those opened by Henriette Niepce and Myriam Prévot in 1951, Iris Clert in 1956 and Ileana Sonnabend in 1963, among others.

In 1951, Paris was home to 168 modern and contemporary art galleries, one out of three of which were run by women. The French press noticed the phenomenon and sarcastically dubbed this new wave of gallery owners “the female popes of abstract art” or “the cartel of abstract art”. These gallery owners (the term “galeriste” was coined in France in the 1960s) came from a variety of backgrounds—some coming from the families of dealers or artists, while others were outsiders, encouraged in this new direction by the social and cultural upheavals of the times. With daring programming, they became essential players in the post-war art market. Promoting artists in France and abroad by circulating works and exhibitions, and liaising with art critics and museum curators, the female intermediaries were pioneers in their field.

ORGANISATION FOR THE PROMOTION OF WOMEN ARTISTS

Changes in both the status of women and the art market provoked debate around the promotion of women artists. In 1971, the art historian Linda Nochlin asked the question: “Why have there been no great women artists?” The art world began to organise itself to address the issue and groups and organisations were established, such as the International Union of Women Architects, which was founded in 1963. In 1972, the painter Charlotte Calmis founded the group La Spirale (1972–1982) in Paris, which brought together women artists. The painter Christiane de Casteras, president of the Union of Women Painters and Sculptors1, created the Dialogue organisation in 1975, which established an annual exhibition of works of art by women artists.

Created in 1976 by the psychoanalyst and painter Françoise Eliet, the Femmes/Art collective brought together about thirty women artists in order to challenge the under-representation of women in Parisian galleries and museums. Aline Dallier- Popper, an art critic specialising in Lyrical Abstraction and contemporary textile art, would also participate in this collective.

In 1985, the essayist Michelle Coquillat founded the Camille organisation to fight for the recognition of women’s art. Also operating as a purchasing fund financed by public aid and private donations, the foundation acquired works created by women artists, which it then exhibited in museums.

Finally, we cannot neglect to mention AWARE (Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions)—a non-profit organisation created in 2014 by Camille Morineau, a heritage curator and art historian specialising in women artists. On the subject of the organisation, Morineau stated: “The primary ambition of AWARE is to rewrite the history of art on an equal footing. Placing women on the same level as their male counterparts and making their works known is long overdue.2”

EXHIBITION OF WOMEN ARTISTS

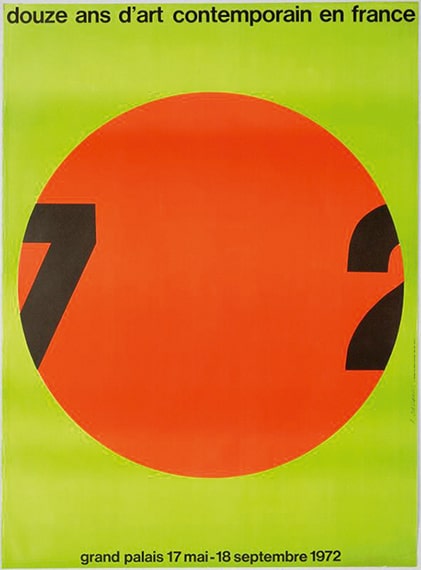

In 1972, the exhibition Douze ans d’art contemporain en France – 1972 was presented at the Grand Palais at the request of Georges Pompidou. This official exhibition attempted to summarise the different artistic trends in France by presenting a selection of works by 72 artists. In the wake of the events of May 1968, the event was highly criticised. Moreover, the exhibition only presented two female artists: Sheila Hicks and Niki de Saint Phalle. The artists Tania Mouraud and Gina Pane had had their works removed from the show in protest. The controversial event provoked an eagerness to present monographic exhibitions of women artists in Paris, as well as group exhibitions of women-only works. One notable example was the retrospective of the artist Hannah Höch at the Musée d’Art moderne in Paris in 1976.

In 1984, Marie Raymond, Huguette Arthur Bertrand and Loïs Frederick took part in the exhibition La part des femmes dans l’art contemporain at the municipal gallery in Vitry-sur-Seine, in the Parisian suburbs. Indeed, the first group exhibitions devoted to women tended to be organised on the outskirts of Paris, the theme reaching the French capital at a later stage.

The question of gender was also addressed in the exhibition Fémininmasculin. Le sexe de l’art at the Centre Georges Pompidou in 1994. As noted in the exhibition catalogue: “The ambition of this exhibition is to show, leaving aside any chronological approach, how the art produced in the 20th century has constantly blurred the biological, anatomical and cultural fates traditionally linked to sex. Approaching art from the perspective of sexual difference does not mean mechanically contrasting ‘masculine’ art with ‘feminine’ art, but rather attempting to show how the works find themselves traversed by this question, beyond the sex—the gender—of the artists who have produced them.3”

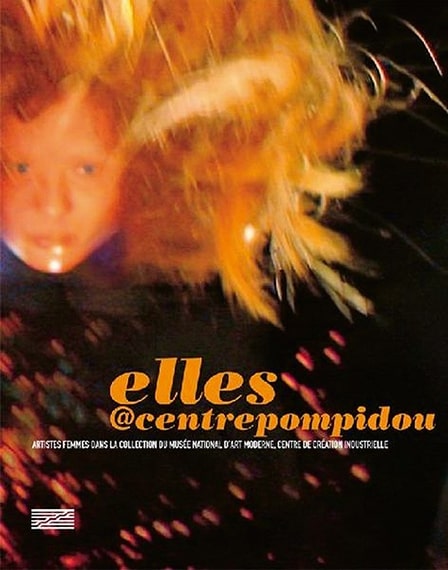

In 1997, the art critic Laura Cottingham organised the exhibition Vraiment : Féminisme et Art, which was presented at Le Magasin – Centre National d’Art Contemporain in Grenoble, France. La Criée centre for contemporary art in Rennes presented the exhibition Revolt, she said! in 2006 with the aim of making contemporary artistic practices visible and questioning the place of women in art history. In the same year, the exhibition What’s new Pussycat? Art et féminisme was presented by the organisation En Plastik at the Ecole Normale Supérieure in Lyon. In 2008, the exhibition 2 ou 3 choses que j’ignore d’elles. Pour un manifeste post (?)-féministe was presented at the Fonds Régional d’Art Contemporain (FRAC) for the Lorraine region in Metz, France. The following year, elles@centrepompidou—a thematic exhibition of the museum’s collections from a female point of view—was inaugurated at the initiative of Camille Morineau, curator at the Musée National d’Art moderne. Lasting two years, the exhibition presenting some 900 works by women artists. Morineau subsequently organised a series of other exhibitions dedicated to women artists, such as L’autre continent at the Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle in Le Havre in 2016 and Women House at the Monnaie de Paris in 2017.

Similar initiatives have since sprung up in increasing numbers. In 2020, the Musée Soulages in Rodez presented Femmes années 50. Au fil de l’abstraction, peinture et sculpture. Notable exhibitions in 2021 include Elles font l’abstraction at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, She-Bam Pow Pop Wizz! Les Amazones du Pop at the Musée d’Art Moderne et d’Art Contemporain (MAMAC) in Nice, and Peintres Femmes, 1780 – 1830 Naissance d’un combat at the Musée du Luxembourg in Paris.

CHOOSING ABSTRACTION

It was amid this climate of growing awareness that our five artists worked. Describing the art scene at the time, the art critic Aline Dallier-Popper wrote: “In the circle of artists that Pierre Restany knew, almost all of whom were abstract artists (the Nouveaux Réalisme movement came later on), there were fewer women than men, and the women who were there, such as Ania Staritsky, Hella Guth, Lutka Pink, Huguette Arthur Bertrand and Marie Raymond (Yves Klein’s mother), were not well known, with the exception of Sonia Delaunay and Vieira da Silva. To my knowledge, none of these artists positioned themselves as women and I did not hear any feminine or feminist demands from them.4”

Indeed, although the artists Marie Raymond, Huguette Arthur Bertrand, Pierrette Bloch, Roswitha Doerig and Loïs Frederick all found it difficult to establish themselves in this male-dominated world, they chose not to express the issue in their works. Looking at their works, it is not possible to guess the gender of the artist that created them. These creations thus demonstrate that women’s experiences can provide insight into the universal human experience, just as well as the experiences of men can.

ABSTRACT ART MEDIA

Each choosing a different abstract style, the five artists expressed themselves primarily through the following three media: painting on canvas, works on paper and textile arts. Far from insignificant, their choice of medium instantly earned them a place at the heart of the history of art.

In the post-war climate, women artists who expressed themselves through painting, particularly those that chose to explore Lyrical abstraction, pursued a path in a particularly male-dominated field. They often had very personal careers, or blended into the predominantly male environment—like Huguette Arthur Bertrand, who chose to “live like a man”. Americans such as Joan Mitchell and Loïs Frederick created additional difficulties for themselves by basing themselves in Paris rather than New York, which was ahead of the game in terms of women’s art, as shown by Helen Frankenthaler’s relatively early recognition there. While they refused to be officially associated with a particular movement or style, these women’s works can be likened to those by Abstract Expressionists or Color Field painters. Joan Mitchell explained: “Abstract is not a style. I just want to make a surface work. This is just a use of space and form; it’s an ambivalence of forms and space. Style in painting has to do with labels. Lots of painters are obsessed with inventing something. When I was young, it never occurred to me to invent. All I wanted to do was paint.5” These female abstract artists worked on canvas with liberated gestures set free by Surrealism, like their male contemporaries, and made their works into visual and individual experiences. Choosing to express their personal forms of abstract art using oil or acrylic on canvas, they established their place in the long tradition of easel painting. They reappropriated the medium—long dominated by men—through their personal use of gesture, form, light and colour.

As a medium, paper was probably available to women artists earlier on because of its low cost and the limited space it required. Without the need for a workshop, drawing on paper could become a secret, intimate form of art. With fast— even non-existent—drying times, techniques on paper were also conducive to experimentation, allowing for great spontaneity. Our five artists used many techniques on paper: watercolour, chalk, ink, gouache, charcoal and pastel, among others. Preventing the artist from backtracking in their work, these spontaneous techniques formed a witness to genius in its most immediate state. Pierrette Bloch wrote: “I like all tools that make lines. I know lines, I frequent them, lines with no conclusion, with no end, their turnings back, their accidents, their apparent speed, their tenacious duration, their persistence, their urgency.” Many women artists have decided to devote themselves to the medium of paper alone for a given period, or for their entire career. This has been the case for Sophie Taeuber- rp, Nancy Spero, Louise Bourgeois and Kiki Smith, among others. A radical choice of medium can express an artist’s protest or an obsession with a theme.

Women artists have been traditionally associated with textile arts. With an almost contemporary approach, Huguette Arthur Bertrand and Pierrette Bloch turned to textiles in the 1970s. Sheila Hicks and Annette Messager also made important contributions to the field. This contributed to a climate of renewal in the art of tapestry, which was accompanied by the reclamation of fields viewed as “women’s culture”. Aline Dallier-Popper thus coined the term “Nouvelles Pénélopes” in 1976, writing: “It is possible to weave and embroider in a different way, which could, all things considered, help to unravel the established order.” The climate in which women artists were showcased encouraged them to re-evaluate an underestimated medium. They made use of a medium traditionally associated with the domestic domain to nurture their artistic investigations. The sewn object became an art object. The historian Rozsika Parker published The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine in 1984, in which she explained how this traditional medium had become a platform for expression and revolt. These women artists became part of Sonia Delaunay’s lineage, as active in the field of textile design as abstract painting. The versatile nature of the textile medium encouraged notions of art and craftsmanship to match it in terms of versatility.

Marie Raymond, Huguette Arthur Bertrand, Pierrette Bloch, Roswitha Doerig and Loïs Frederick formed part of a climate of empowerment and renewal for female artists. Born out of feminist struggles, the movement gradually spread throughout the art world, reaching schools, galleries and institutions. Initiatives for the promotion of female visual artists have multiplied exponentially since the 1970s. The artists themselves have chosen whether or not to reflect this issue in their works.

Each of the five painters presented here has developed a very personal approach to abstract art. Brought together here, the different journeys and forms of artistic expression of this group of women can help us understand the plurality of female artistic creation in Paris in the second half of the 20th century.

Mathilde Gubanski

February 2021

1 – The Union of Women Painters and Sculptors (the Union des femmes peintres et sculpteurs or UFPS in French) was the first society for the promotion of women artists in France. Founded by the sculptor Hélène Bertaux (1825–1909) in Paris in 1881, the Union was one of the longest running artistic organisations, operating until 1994

2 – https://awarewomenartists.com/

3 – Fémininmasculin. Le sexe de l’art, exhibition catalogue, Centre Pompidou, Paris, 1994

4 – Aline Dallier-Popper, Art, féminisme, post-féminisme, Un parcours de critique d’art, L’Harmattan, Paris, 2009

Douze ans d’art contemporain en

France, Grand Palais, Paris, 1972

La part des femmes dans l’art contemporain,

Galerie municipale de Vitry-sur-Seine, 1984

elles@centrepompidou

Centre Pompidou, Paris, 2009 Untitled, 2006

Women House

La Monnaie de Paris, 2017

Femmes années 50. Au fil de l’abstraction, peinture et sculpture

Musée Soulages, Rodez, 2019

She-Bam Pow POP Wizz ! Les Amazones du Pop

MAMAC, Nice, 2020

MARIE RAYMOND

(1908-1989)

EXHIBITED ARTWORKS

Marie Raymond in her studio, Paris, c. 1948

Photo : J. Bokma – E. De Vrie

SANS TITRE - UNTITLED, 1963

Oil on canvas

96 x 130 cm – 37 13/16 x 51 3/16 in.

Signed “M.Raymond” lower right

Galerie Diane de Polignac, Paris

ENFERMÉS DANS LES FORMES, 1976

Acrylic on canvas

92 x 73 cm – 36 1/4 x 28 3/4 in.

Signed, dated and titled “M. Raymond 1976 Enfermés dans les formes” on reverse

Galerie Diane de Polignac, Paris

SANS TITRE - UNTITLED, C.1975

Gouache, ink and charcoal on paper laid down on canvas

50 x 65 cm – 19 11/16 x 25 9/16 in.

Signed “M.Raymond” lower right

Signed “M.Raymond” on reverse

Galerie Diane de Polignac, Paris

BODY FOR WORK ANALYSIS

Marie Raymond

Organist of light1

1 Pierre Restany, Marie Raymond, Organiste de la lumière, May 1957

THE FORMATIVE YEARS

Marie Raymond was born in the South of France in 1908, in La Colle-sur- loup. As a teenager, Marie Raymond began practising yoga, which was still uncommon in Europe at the time. The artist also developed an interest in esotericism and the cosmos at a young age. Marie Raymond trained as an artist by painting the subject of landscapes in the South of France. “Then the war set in with all of its anguish, restrictions and tragedies, which we went through under the indifferent sun”1. During this period, Marie Raymond created her Paysages imaginaires [Imaginary Landscapes] (1941–1944) inspired by her walks in the hinterland. These surrealistinspired landscapes featured sombre palettes, sinuous lines and mysterious titles. It was then that Marie Raymond asked the question: “Doesn’t painting tell the stories of our lost dreams, or those to come?”2

THE POST-WAR PERIOD IN PARIS

At the end of the war, Marie Raymond chose abstraction. She wrote: “I once again feel the need to express something, but what? The sun is still shining! But there is nothing tangible. How do you piece life back together? This is how the first step towards abstract painting is made. (…) I was trying to construct a world, with the elements of colour and lines: to compose an elsewhere, with what I could feel of the exhilarating light of Space, of the need to live.”3 This abstraction was nourished by memories of the colours and light in the South of France. The paintings of Marie Raymond would be truly radiant. Based in Montparnasse, Marie Raymond formed friendships with the artists Jacques Villon, Frantisek Kupka, and most importantly Piet Mondrian – with whom she shared her studio. It was probably these artists who encouraged Marie Raymond to explore a more constructed style of abstraction.

Marie Raymond’s palette was composed of warm and luminous colours. She described what lay behind this very personal decision: “I could feel this scattered life, which had to be pieced together as a whole, to express the inner states which, for me, contained the gifts of the Impressionists: the light of the south – Hope. For me, it was that, and an impulse that pushed me to express it. All these scattered harmonies, I had to bring them into the light.”4 In the post-war climate, Marie Raymond turned to the sun’s rays to guide her artistic practice. In addition to being a painter, Marie Raymond was an art critic, publishing numerous articles. She also wrote poems, which form true counterparts to her luminous paintings.

MARIE RAYMOND & IMPRESSIONISM

Marie Raymond particularly appreciated the Impressionists, calling the artists “les maîtres de la lumière” [“the masters of light”]. Marie Raymond was struck by their observations of nature and the effects of light: “All of our Impressionists sought out ever closer proximity to nature, to distil the truth around them. Space and light were always drifting between their gaze and the forms they observed, preventing them from fully grasping them. The dissociations of light around things separated them from those things, taking them beyond.”5 Marie Raymond was also attentive to the teachings of Matisse on colour – she was a great admirer of the artist, who she interviewed in 1953 for the Japanese magazine Mizue. Her work evolved during the 1950s, as she adopted a more “naturalist” style.

MARIE RAYMOND: THE COSMOS & ESOTERICISM

In 1957, Pierre Restany wrote about Marie Raymond: “The universe of Marie Raymond retraces the beautiful story of light and its myriad of games through a diffuse space, a sacred place of this complete saturation. Here, the trajectories of the sun’s rays—sometimes direct, sometimes grouped in contradictory nebulae—create the dynamic elements of a subtle meridian atmosphere where the scattered memories of ancient natural structures come together and merge. (…) The journey on which Marie Raymond invites us—in an elevated atmosphere, in the full warmth of her light hues—is steeped with an infinite number of sparkling encounters, where the Berthe Morisot of abstract painting succeeds in bestowing chromatic bursts with that delicate, full touch, that distinctive accent. Her work, imbued with the serene joy of spring mornings, has managed to capture the flavour of a melodious secret (…) ”6

Marie Raymond continued her exploration of light through a theme that had fascinated her since her teenage years: the cosmos. Going beyond representations of the effects of light, Marie Raymond wanted to reach the stars: “To bring a world into being, is it not true that stars must be born?” She explained: “I have always remembered a line from an opera, which I heard in Nice. It was Antar, I think. The line, which has stayed lodged in my memory, resonated very strongly with me: ‘And one can, with the beat of a wing, fly away to the Sun’”7. This line, which profoundly affected Marie Raymond, is evocative of both her fascination with the stars and the dazzling career of her son, Yves Klein.

Indeed, the premature loss of her son in 1962 plunged the luminous Marie Raymond under a blue shadow for quite some time. The artist returned to painting and created a more “psychedelic” style of art that was oriented definitively towards esotericism and the cosmos.

ABSTRACTION-FIGURES-ASTRES

In 1964, Marie Raymond began painting a series of works that she called Abstraction- Figures-Astres [Abstraction-Figures-Stars]. The works in the series were characterised by a restless touch that whirled over the surface of the canvas. In 1966, Georges Boudaille and Jean Cassou wrote about Marie Raymond: “It was a delicate yet powerful melody that was born from the rhythms of colour. What a colourist! So full of vivacity with her reds, pinks and mauves, which developed in harmonious contrast with acid, brutal and luminous greens. From this explosion of violence, subtle poetry was born, full of nuances, which did not fade away when we moved away from the work, and has not faded from our memories ever since.”8

Marie Raymond’s works once again possessed that mysterious aspect reminiscent of her “surrealist” works from the early 1940s. Playing on the boundaries between abstraction and figuration, the artist populated this imaginary cosmos with anthropomorphic forms. She wrote: “I remember learning that the Persians had practised the cult of Mithra, goddess of light. This cult from antiquity was said to have spread to the ancient city of Lutetia, which is, as everyone knows, our city of Paris today.”9 Even in her darkest moments, Marie Raymond was searching for clarity: “‘The night is not the night’, because there will be dawn, hope”10.

1 Marie Raymond, Notre vie

2 ibid

3 ibid

4 ibid

5 Marie Raymond, Les maîtres de la lumière, published in “Des meesters van het licht”, Kroniek van Kunst en Kultuur (Amsterdam), No. 1, January 1948, p. 27–28

6 Pierre Restany, Marie Raymond, Organiste de la lumière, May 1957

7 Marie Raymond, Notre vie

8 Georges Boudaille and Jean Cassou, invitation card for the exhibition Peintures de 1960 à 1966 de Marie Raymond, 1966

9 Marie Raymond, Les maîtres de la lumière, published in “Des meesters van het licht”, Kroniek van Kunst en Kultuur (Amsterdam), No. 1, January 1948, pp. 27–28

10 Marie Raymond, La nuit de l’été 76, published in + – 0 (Brussels), No. 15, December 1976, p. 21

RYTHMES, 1946

Oil on canvas

82 x 142 cm.

Fondation Gandur pour l’art, Genève

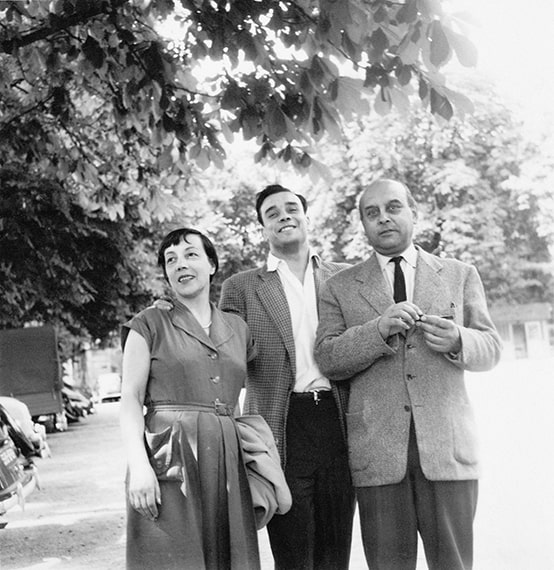

Marie Raymond

Galerie Cavalero, Cannes, 1963

Marie Raymond

Biography

THE FEMALE PAINTER MARIE RAYMOND’S YEARS OF STUDIES

Marie Raymond was born on May 4th, 1908 at La Colle-sur-Loup in the south of France, into a Provencal bourgeois family. Her father was a pharmacist and her grandfather was a flower and perfume merchant. Marie Raymond studied in the Blanche de Castille boarding school in Nice. From her adolescence, she practiced yoga, which was still rare in Europe at the time. This unusual interest in yoga and occultism came from her older sister Rose and her husband, a doctor.

Marie Raymond discovered her vocation for painting on visiting the studio of Alexandre Stoppler, a painter based in Cagnes-sur-Mer. He trained the young artist by getting her to paint directly from life. Her memories of the scents, colours and light of the south of France determined the future development of Marie Raymond’s painting. She wrote: “From my early childhood, the memory of playing among mountains of cut roses that my grandfather bought all over the countryside has remained strong.” The south of France attracted a lot of artists, many whom visited Cagnes-sur-Mer to paint. This is how Marie Raymond met the painter Fred Klein whom she married in 1926. She was just eighteen years old.

Two years later, Fred and Marie had a son: Yves Klein. Marie Raymond had the intuition very quickly that her son would be famous: “I was already aware and desired one day to have a son who would be famous. I have always very clearly remembered a phrase from an Opera I heard in Nice. It was Antar, I think, a phrase stayed in my memory that echoed very strongly in me: ‘and one can, with the beat of a wing, fly away to the Sun’, sung of course. And when I consider life, Yves’s momentum, I can’t help finding in it something like the prescience of destiny which was realized, achieved by Yves Klein’s life in its meteoric evolution.”

MARIE RAYMOND’S LIFE BETWEEN PARIS AND THE SOUTH OF FRANCE

The Klein family regularly moved back and forth between Paris and the South, between the desire to live in the art world and economic reality. In Montparnasse, they lived a bohemian life among their friends the artists Jacques Villon, Frantisek Kupka, and especially Piet Mondrian with whom Marie Raymond shared her studio. As she described: “It was like a family, many brothers who found each other and had fun in endless conversations. I still remember chatting to Mondrian, at the Dancing de la Coupole. I wasn’t yet twenty, he was sixty, but he was so happy to be dancing.” Between the south of France and the Netherlands, another painter influenced Marie Raymond: Van Gogh, whose Gardener she first saw, in the form of a coloured print, at Jacques Villon’s home.

Back in Nice in 1932, Marie and Fred became close to Nicolas de Staël and his first wife, Janine Teslar. The painter Marie Raymond attended classes at the Nice school of decorative arts where she met the sculptor Émile Gilioli. She was awarded the commission for a fresco for the pavilion of the Alpes-Maritimes at the International Exposition of 1937. In 1938, Fred Klein exhibited in Amsterdam and the family took advantage of this to visit the Netherlands. At the start of the war, the family settled in Cagnes-sur-Mer where Marie Raymond started to paint Imaginary Landscapes (1941-1944), inspired by her wanderings in the hinterland; this is when she met Hans Arp and Alberto Magnelli.

At the end of the war, the woman artist Marie Raymond left her post-Surrealist period and chose abstraction definitively: “gradually, you become internalized, you work. I again sensed the need to express something, but what? The sun still shines! But nothing tangible. How do you recompose life? This is how the first step towards abstract painting is taken.” She made herself a place in the Parisian art scene, which was essentially masculine at the time. Until 1954, Marie Raymond opened her apartment- studio every Monday, creating the “Mondays of Marie Raymond” where the gallerists Colette Allendy, Iris Clert, artists Pierre Soulages, Raymond Hains, François Dufrêne, Jacques de la Villeglé, César, Eugène Ionesco, Jean Tinguely, Hans Hartung, and Nina Kandinsky, as well as the critics Charles Estienne, Pierre Restany, and Georges Boudaille would gather. Pierre Soulages said: “We would go, especially in the evening, for a coffee. We were close, Colette and I, and also our friend Hartung who liked Marie’s painting a lot.”

Marie Raymond was also an art critic. She published many articles, especially in the Dutch magazine Kunst en Kultuur for which she was the Paris correspondent from 1939 to 1958.

RECOGNITION FOR THE PAINTER MARIE RAYMOND

In 1945, Marie Raymond participated in her first major exposition at the Salon des Surindépendants. Her work was hung alongside pieces by Hans Hartung, Jean Dewasne, Jean Deyrolle and Gérard Schneider. The following year, Marie Raymond participated in the exhibition La Jeune Peinture Abstraite at the Galerie Denise René.

The same year, she exhibited with Serge Poliakoff and Engel Pak at the Centre de Recherches d’Art Abstrait in Paris and then at the first Salon des Réalités Nouvelles. In 1949, she was awarded the Kandinsky Prize with Youla Chapoval and at the Galerie de Beaune an exhibition was held entitled Les gouaches de Marie Raymond. This woman artist also participated in the first São Paolo Biennale in Brazil.

In 1951, Marie Raymond presented her work with Arp, Doméla, Magnelli, Poliakoff, amongst others at the travelling exhibition Klar Form – 20 Artistes de l’École de Paris organized by Denise René. This exhibition travelled to Copenhagen, Helsinki, Stockholm, Oslo and Liège. In 1952, Marie Raymond exhibited at the Salon de Mai. She interviewed Matisse for the Japanese magazine Mizue.

In 1953, the Klein couple exhibited for three days at the Franco-Japanese Institute of Tokyo and at the Bridgestone Museum of Art in Tokyo. Marie was given a solo show at the Museum of Modern Art of Kamakura.

Fred and Marie participated in 1955 in a travelling exhibition of the Der Kreis (The Circle) Group in Austria and Germany. Marie Raymond then exhibited at the Rio de Janeiro Museum of modern art and at the Lausanne Musée Cantonal. In 1957, an important retrospective called Marie Raymond was held at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. In 1960, she entered the Marzotto Prize and won a prize for France with the painter Dimitrienko.

At that time, the painter Marie Raymond’s form of abstraction was luminous and lyrical. “For those who haven’t understood the Abstract process, I will try to give a few indications of my working method. After preparing canvases and colours, I would go outside to penetrate myself with the day’s light, walk, even run a little in the Luxembourg gardens near my home, so as to distance myself from the material gesture. For many years, on coming back home, I would focus by reading a few pages from Bergson’s Creative Evolution, which is so full of images, so poetic. With this backbone: having reached a certain internal rhythm, I approached the canvas. A harmony having been revealed, the next stage was tuning and the rhythm of this internal state reached beyond reality and was experienced internally, something beyond the tangible, a chord with ‘the immaterial’ in summary that Yves made light, later on.”

Then came the difficult years for the artist Marie Raymond. The Kleins separated in 1958 and divorced in 1961. The following year, Yves Klein married Rotraut Uecker and died that year of a heart attack at the age of only thirty- our. Marie Raymond said: “Yves had prepared a painting of gold and still had a bouquet of artificial roses separately, taking the bouquet in his hands, he placed it on the painting and asked me the question: “What does this make you think of?” (…) These paintings, he called them “tombs”. Was it a premonition? Because he was in perfect health and very active: This was in the spring, his wife was expecting their child. Who could have foretold that a few months later, he would be carried off so suddenly, in the prime of life, while accomplishing his work.” Marie Raymond’s father also died of a heart attack in 1963.

The artist Marie Raymond’s painting was changed forever by these experiences. The painter found inspiration again in her passion for esotericism and the Cosmos. From 1964, she painted a series of works that she called Abstraction-Figures-Astres. Marie Raymond exhibited at the Galerie Cavalero in Cannes at the Fondation Maeght at Saint Paul-de-Vence and at the Galerie aux Bateliers in Brussels. In 1966, Daniel Templon opened his first gallery, the Galerie Cimaise Bonaparte, with an exhibition of Marie Raymond. In 1972 a major show of her work and of her son, Yves Klein, was organized at the Château-Musée of Cagnes-sur-Mer. In 1988, the Pascal de Sarthe Gallery in San Francisco dedicated a solo exhibition to Marie Raymond. Three times, works by her were shown at the Centre Pompidou in Paris: in 1977, in the exhibition Paris – New York, in 1981, in the exhibition Paris – Paris, Créations en France 1937 – 1957, and finally in 1988 during the exhibition Les années 50. Marie Raymond died the following year in 1989.

HUGUETTE ARTHUR BERTRAN

(1920-2005)

EXHIBITED ARTWORKS

Huguette Arthur Bertrand in her studio, Paris, c. 1954

Photo : Droits réservés – Reserved rights

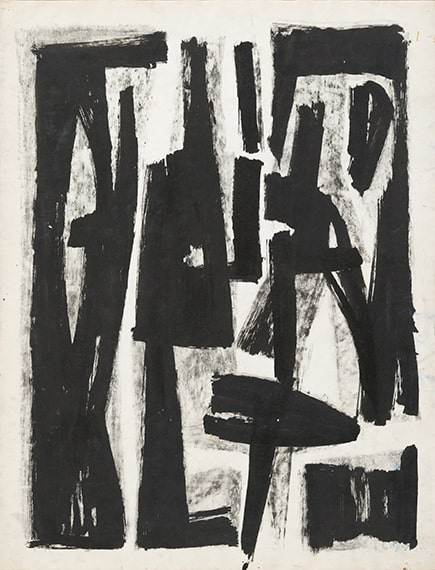

SANS TITRE – UNTITLED, C.1959

Ink on paper

105 x 76 cm – 41 5/16 x 29 15/16 in.

Signed “Hug Arthur Bertrand” on reverse

Galerie Diane de Polignac, Paris

RAZ DE MARÉE, C.1960

Oil on canvas

162 x 130 cm – 63 3/4 x 51 3/16 in.

Signed “Hug Arthur Bertrand” lower right

Titled “Raz de Marée” on reverse

Galerie Diane de Polignac, Paris

TORRENT, C.1980

Oil on canvas

195 x 130 cm – 76 3/4 x 51 3/16 in.

Signed “Hug Arthur Bertrand” lower right

Titled and signed on reverse

Galerie Diane de Polignac, Paris

BODY FOR WORK ANALYSIS

Huguette Arthur Bertrand

Elated painting

GEOMETRIC ABSTRACTION

In the immediate post-war period, Huguette Arthur Bertrand attended the Académie de la Grande Chaumière. Immersing herself fully in the effervescence of the Saint-Germain-des-Prés art world, she became friendly with Serge Poliakoff, Pierre Dmitrienko, Jean-Michel Atlan and many others. Huguette Arthur Bertrand participated in the vitality of artistic liberation that coincided with the end of a global conflict. The Paris art scene was animated by debates between figuration and abstraction, but also between geometric abstraction and gestural abstraction.

After working for a short time with figurative painting, Huguette Arthur Bertrand began to experiment with making forms geometric, following on from Cubism. Her compositions were split and given rhythm by lines, she wanted to “tear up the shape without denying it”. In 1951, Huguette Arthur Bertrand exhibited at the Galerie Niepce in Paris, and in 1949 and 1950, at the key exhibition at the Galerie Maeght, Mains Éblouies (Dazzled Hands). She won the famous Prix Fénéon in 1955. Huguette Arthur Bertrand regularly participated in the main salons of abstract art in Paris: at the Salon de Mai from 1959 until the late 1980s, at the Salon des Réalités Nouvelles from 1950 until the 1990s and at the Salon d’Automne. Around 1950, Huguette Arthur Bertrand’s abstraction was restrained. Her works were built up with juxtapositions of areas of cold colours.

GRAPHIC ABSTRACTION

During the 1950s Huguette Arthur Bertrand’s work evolved. The geometric shapes, which by then were definitively abstract, spread over the surface of the canvas, and the whole composition was highlighted with strong hatching. Huguette Arthur Bertrand developed this split graphic style on both canvas and paper. Her work with ink shows her confidence and great mastery of gesture. Huguette Arthur Bertrand’s work was shown abroad. A solo exhibition was held at the Meltzer Gallery in New York in 1956 and then in Brussels at the Palais des Beaux-Arts in 1957. The same year, the painter Huguette Arthur Bertrand was also included in the exhibition New Talents in Europe at the University of Alabama. In 1958 and again in 1960-1961, she exhibited at the Howard Wise Gallery in Cleveland.

GESTURAL ABSTRACTION

Huguette Arthur Bertrand used hatching and highlights to create her compositions, dividing the canvas surface. Her process is decisive: the form in space counts most of all. Colour comes in second place and is a support for her artistic experiments. The artist’s palette evolved towards warm colours: red, ochre, brown. This limited range accompanied the elated lyricism of the 1960s. Huguette Arthur Bertrand’s painting became more and more gestural, free, and versatile. “They are things that fly, abstract objects that make faces, movements that cut through space” wrote Michel Ragon.

The artist’s volcanic character is found in the warm palette and the confident gesture of her works, also emphasized by her intense titles: Raz de marée (Tidal wave), Cela qui gronde (What rumbles), Torrent (Stream), Foudre (Lightning), Écume noire (Black spume)…Huguette Arthur Bertrand explained “I wanted to invent spaces, as if they were moving, using the resources of painting.”

TEXTILE ABSTRACTION

From 1971, Huguette Arthur Bertrand turned towards tapestry and was given commissions by the Mobilier National. This was an opportunity for her to develop her art. Huguette Arthur Bertrand continued the renewal of tapestry that Jean Lurçat had started. She combined painting and fabric equally in collages where rags used to wipe paint brushes contribute forms and colours to the composition. These courageous works show a desire to fit into a contemporary vision of textile art, between painting and object and between art and craft.

In 1976, the art critic Aline Dallier-Popper wrote about the relationship between women and textile creation and invented the term of “New Penelope” that applies perfectly to Huguette Arthur Bertrand.

AERIAL ABSTRACTION

At the turn of the 1980s, Huguette Arthur Bertrand’s monochromatic painting became more fluid and invaded the entire surface of the canvas. The compositions became aerial, pacified and poetic. A few waves are placed gently on the canvas. These works recall Joseph Sima’s art, whom she had met in Prague in 1946. The diluted colours allow subtle transparent and light effects to appear.

The paintings of the 1990s are silent and delicate, the artist shows us her great sensitivity.

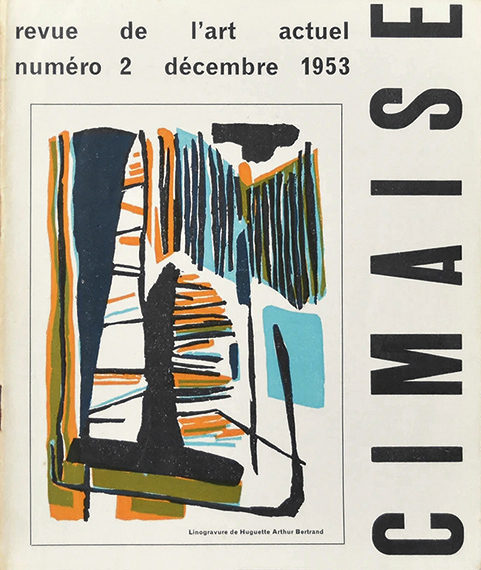

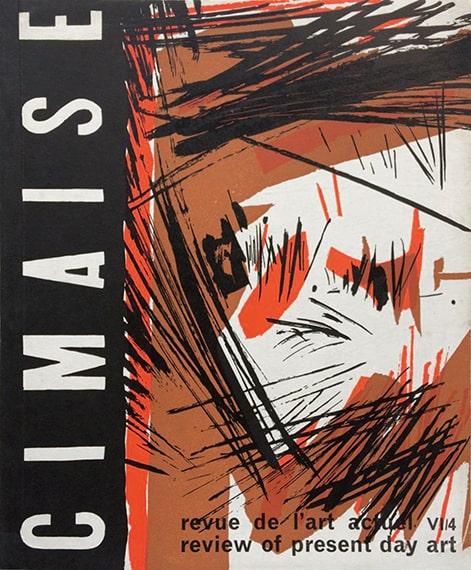

Arthur Bertrand en 1ère de couverture Cimaise Magazine, n°2, 1953, with a Huguette Arthur Bertrand’ work on the front cover

Revue Cimaise, n°4, 1959, avec une oeuvre d’Huguette Arthur Bertrand en 1ère de couverture Cimaise Magazine, n°4, 1959, with a Huguette Arthur Bertrand’ work on the front cover

Huguette Arthur Bertrand

Biography

A YOUNG WOMAN PAINTER IN POST-WAR PARIS

Born in 1920 in Écouen, Huguette Arthur Bertrand spent her childhood in Roanne (center south of France) and settled in Paris shortly after the war. She attended the Académie libre de la Grande Chaumière. A fellowship allowed her to spend a year in Prague between 1946 and 1947 where she had her first solo exhibition. She met the painter Joseph Sima there.

A rare painter woman in the essentially masculine artistic landscape of Postwar Paris, she immersed herself fully in the buzzing art world of Montparnasse and Saint-Germain-des-Prés. Huguette Arthur Bertrand became friendly with publishers, critics (Michel Ragon) and abstract artists, those of the Galerie Denise René: Jean Dewasne, Jean Deyrolle, Serge Poliakoff; and with Martin Barré, Pierre Dmitrienko, James Guitet, Kumi Sugaï and John F. Koenig. On Saturdays she would visit Jean-Michel Atlan’s studio with Marcelle Loubchansky. She participated with passion in this artistic effervescence, marked by lively debate between figurative and abstract art, but also between supporters of “cold” abstraction and those of “warm” abstraction: one geometric, the other gestural, lyrical, guided by a free and spontaneous gesture.

IN THE 1950’S, HUGUETTE ARTHUR BERTRAND’S SUCCESS IN PARIS

During the 1950s, Huguette Arthur Bertrand applied the full force of her art and the confidence of her artistic vocabulary made from stripes that hatch, streak, give rhythm to compositions. A powerful way of painting that confuses. A solid form of painting that marks a determined, independent character, “a type of painting that does not appear feminine at all; even muscular painting, strong, dynamic in a way that would appear masculine […]” as Michel Ragon wrote.

The woman artist Huguette Arthur Bertrand’s explosive work, which was definitively abstract from 1950, presents an audacious palette, full of colour that gradually evolved towards more dramatic shades, concentrated in a range of ochre, brown, orange-red.

In 1949 and 1950, Huguette Arthur Bertrand participated in the key exhibition Les Mains Éblouies (The Dazzled Hands) at the Galerie Maeght alongside Pierre Dmitrienko, and with Cobra artists in 1950 (Pierre Alechinsky, Corneille, Jacques Doucet). In Paris, from the start of the 1950s, several galleries exhibited the painter woman’s work: Galerie Niepce, Galerie La Roue, Galerie Arnaud above all…

Huguette Arthur Bertrand regularly participated in the main salons of abstract art in Paris, at the Salon de Mai from 1949 until the late 1980s, at the Salon des Réalités Nouvelles until the 1990s, and at the Salon d’Automne. The year 1955 was decisive for her: she won the famous Prix Fénéon (Fénéon award). In 1956, Huguette Arthur Bertrand participated in the Festival de l’Art d’Avant-Garde, a major event held at Le Corbusier’s Cité Radieuse in Marseille.

HUGUETTE ARTHUR BERTRAND’S INTERNATIONAL RECOGNITION

Her works began to travel abroad: a solo exhibition was held at the Brussels Palais des Beaux-Arts in 1956, and crossed the Atlantic: in 1956, the Meltzer Gallery in New York organized for the woman artist a solo exhibition in 1956, praised by critics, then a group show the year after: North and South Americans and Europeans. Also in 1957, the painter Huguette Arthur Bertrand participated in the exhibition New Talents in Europe at the University of Alabama. In 1958 and in 1960-61, she exhibited at the Howard Wise Gallery in Cleveland.

The works of the painter woman Huguette Arthur Bertrand continued to be exhibited in many different galleries and art events all over the world: in Germany, Austria, Belgium, the Netherlands, Denmark, England, Italy… as far as Japan, Venezuela, Mexico and Cuba. In 1962, Jean-Marie Drot interviewed Huguette Arthur Bertrand in her studio as part of L’oeil d’un critique program, directed for French television (ORTF).

THE WOMAN ARTIST HUGUETTE ARTHUR BERTRAND IN MICHEL RAGON’S CIRCLE OF FRIENDS

Close to the art critic, Michel Ragon, Huguette Arthur Bertrand met his circle of friends: Pierre Soulages, Hans Hartung, Gérard Schneider, Zao Wou-Ki, Victor Vasarely, among others. Together they worked on a collection La Peau des Choses (the skin of things), a portfolio of prints published in a limited edition by Jean-Robert Arnaud in 1968 in honour of their friend Michel Ragon.

HUGUETTE ARTHUR BERTRAND’S MATURITY WORK

Starting in 1971, Huguette Arthur Bertrand worked with tapestry for over a decade (she received commissions from the Mobilier national) and became interested in monumental mural painting. At the turn of the 1980s, her gestures became more and more liberated, and calmer, summarized in subtle white traces, airy like a breath on the canvas. The woman artist Huguette Arthur Bertrand died in 2005.

PIERRETTE BLOCH

(1928-2017)

EXHIBITED ARTWORKS

Pierrette Bloch, Bages, 2006

Photo : James Caritey

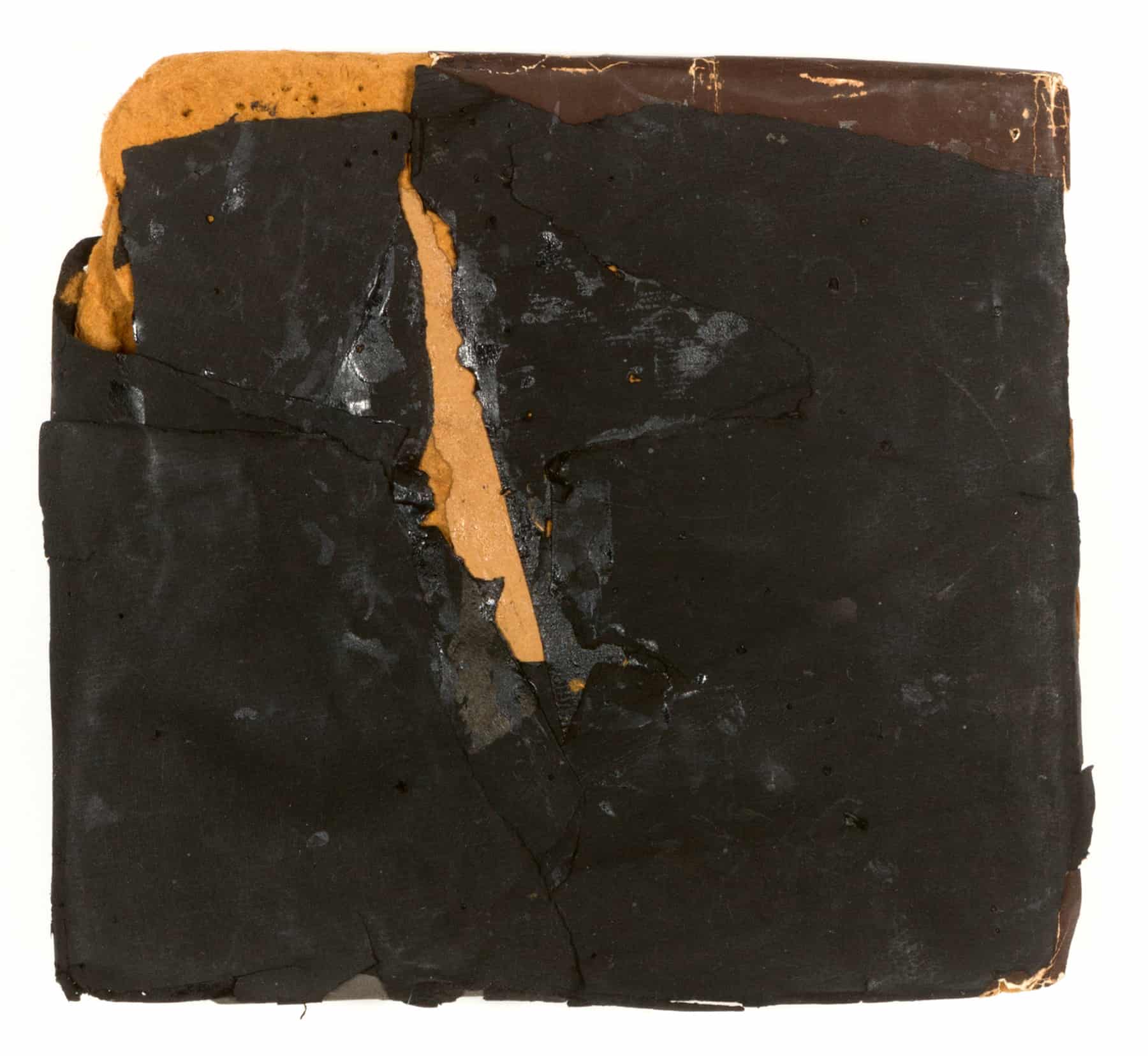

COMPOSITION 1968, 1968

Collage on masonite

20 x 22 cm – 7 3/4 x 8 5/8 in.

Numbered C 24 on reverse

Galerie Diane de Polignac, Paris

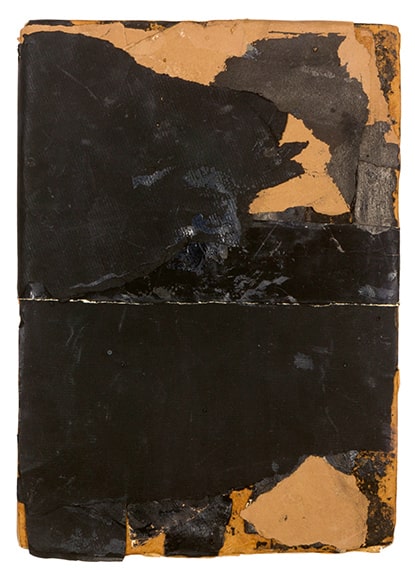

COMPOSITION 1969, 1969

Collage on masonite

28 x 20 cm – 11 x 7 3/4 in.

Numbered C 01B on reverse

Galerie Diane de Polignac, Paris

UNTITLED, 2000

Indian ink on paper

105 x 75 cm

Centre Pompidou, Paris

MAILLE N°8, 1974

Fabric, nylon and ribbon

218 x 334 cm

Musée d’Art moderne de Paris

BODY FOR WORK ANALYSIS

Pierrette Bloch

The “Silent, discreet work1”

1 – Michel Parmentier, “Sans doute”, 15 June 1992, text published on the invitation card of the exhibition Pierrette Bloch, dessins de crin, Galerie de France, Paris, 1992

TIME

The origins of Pierrette Bloch’s work can be traced back to her childhood. Coming from a family of Swiss watchmakers, Bloch developed her work around the passing of time. Stretching out her lines of ink and fibre lengthwise, she created compositions reaching up to 10 metres across. These far-reaching works extend so far that they cannot be appreciated at a glance. Viewers must move along their compositions to be able to discover them as a whole: “The longer the thread, the more unforeseeable things it offers.” The artist’s work can be gradually appreciated piece by piece like an East Asian painting on a scroll that is unrolled little by little to be read progressively. These stretching lines become timelines in themselves. Bloch’s works are like pieces of music: they are appreciated over time.

MUSIC

Pierrette Bloch’s repetitive compositions of similar and irregular dots, arranged in lines on sheets of paper, are reminiscent of musical scores. The countless circles in ink or loops of threads give rhythm to the composition—there are keys, punctuation marks, moments of silence, breaths. The viewer looks at the work as if following a rhythm, appreciating a silent form of music that is experienced on an individual level. Like most abstract artists, Bloch was a music lover. She particularly appreciated the minimalist music that she discovered in the 1970s—an art form perfectly suited to Bloch’s creations, as it was composed by the repetition of short patterns.

MATERIALS

Pierrette Bloch’s mother grew up in Japan: the land of ink and paper. One can imagine that these memories influenced Bloch in her choice of materials. The artist was guided by the materials themselves in the execution of her works, much like the artists of the Japanese Gutai group: “Gutai art does not change the material: it brings it to life. Gutai art does not falsify the material. In Gutai art the human spirit and the material reach out their hands to each other, even though they are otherwise opposed to each other. The material is not absorbed by the spirit. The spirit does not force the material into submission. If one leaves the material as it is, presenting it just as material, then it starts to tell us something and speaks with a mighty voice.1” For Pierrette Bloch, her choice of tools and materials was a response to her choice of paper or Masonite panels. The importance given to materials in the artist’s work can also be likened to the Supports/Surfaces movement that developed in France at the end of the 1960s.

WRITING

Abstraction was an obvious choice for Pierrette Bloch, who rejected a narrative approach and thus developed a very personal form of writing made up of a multitude of signs. Containing no specific meaning, Bloch’s writing is closer to a form of inscription, demonstrating an instinctive, primary quality. The black loops on the paper are reminiscent of how children approach writing, or the “doodles” we make to occupy or distract ourselves because they help to pass the time or concentrate. Bloch said that she grew up surrounded by adults, “And while they were talking together, I made little drawings.” The lack of message in the artist’s writing, which existed for itself, can be likened to the work of the BMPT art group (Daniel Buren, Olivier Mosset, Michel Parmentier and Niele Toroni) created in 1966. The group’s works are indeed characterised by the repetition of a chosen motif.

There is an almost tribal element in Bloch’s relentless scripts that evokes the first lines drawn by man on the walls of caves. The multitude of signs she inscribed gave rise to an individual, illegible and fundamentally abstract form of writing that invaded the surface of her works, recalling the all-over painting style developed by the American artist Mark Tobey. Bloch’s writing was not intended to seek perfection. Immediate and without repentance, each mark and dot appears different because of its accidental, random and organic nature.

SPACE

Pierrette Bloch invaded the surface of her works with a multitude of signs. She particularly liked horizontal spaces, exploring long compositions with lines that she stretched out to the extreme. The artist’s distinct appropriation of space was very rare in Western art. Bloch succeeded in invading space while eschewing the monumental, representing a restrained, minimalist exploration combining time and space. The artist also invaded space with her fibre sculptures, composed using a flexible and fine type of material that assumed its full scope through extension and a myriad of knots. The artist’s long constructions cast a shadow on the wall, allowing the composition to take up even more space. Invading the third dimension, the artist’s work is perpetually transformed by the slightest draught or change in light.

BLACK

Pierrette Bloch’s body of work is characterized by an extremely limited palette. The colour of the background ranges from the different whites of paper to the browns of Masonite panels. While a few touches of blue appear from time to time, black was the artist’s colour of choice. In the artists own words: “For me, black was sometimes a coat, sometimes a trace, sometimes a line. The states of black: sensuality, Jansenism, restraint, opacity, radiance – whoever encounters them has not chosen them but rather experienced them with surprise. They find in them the place, the circumstances where something could happen.” Bloch explored all the possibilities of contrast between black and white, and also between two whites and between two blacks, by highlighting their contrasting textures and glosses.

MINIMALISM

Pierrette Bloch spent some time in the United States in the 1960s, where she discovered the minimalist trend that set itself in opposition to the lyricism of Abstract Expressionism and the figurative approach of Pop Art. The heir to the Bauhaus movement and its motto, “Less is more”, minimalism represented an art of subtraction, of stripping back. The trend developed throughout the world in the 1960s and Bloch fitted perfectly into the new climate. Rejecting the dramatic, along with illusionism and virtuosity, the artist’s work was a practice of restraint. In the 1960s, Bloch abandoned the “noble” medium of oil painting on canvas to work on paper and Masonite. She developed a restricted pictorial language of dots and lines repeated ad infinitum, her palette reduced to the extreme. The repetition and arrangement of Bloch’s strokes on the background were a response to the artist’s inner rhythms. Pierrette Bloch thus created a truly intimate form of abstract art, as she said in her own words: “I want to be rather than to grasp.”

1 – The Gutai Manifesto, the movement’s founding text written by Jirō Yoshihara, originally published in the Geijutsu shincho [New Artistic Trends] art journal, Tokyo, December 1956

Pierrette Bloch

Biography

PIERRE BLOCH’S EARLY LIFE AND ARTISTIC TRAINING

Pierrette Bloch was born in Paris on 16 June 1928. The Bloch family fled to Switzerland to escape occupied France when war broke out. In 1939, Pierrette Bloch was struck by her first aesthetic revelation when she encountered the masterpieces of the Museo del Prado, which were on show in Geneva at the time. Pierrette Bloch immersed herself in literature, which became an important source of inspiration for the young artist. She also attended conferences on art history, including a lecture by the curator and historian René Huyghe on the theme of linearity, which led her to establish an artistic practice based on the relationship between drawing, time and writing.

MEETING PIERRE SOULAGES

After the end of the Second World War, Pierrette Bloch returned to Paris where she studied law and literature. Turning her attention to drawing and painting, she joined the studio of Jean Souverbie in 1947. The following year, Pierrette Bloch studied with André Lhote and then Henri Goetz in their studios. The latter introduced Bloch to the painter Pierre Soulages, with whom she developed a close friendship. Influenced by Pierre Soulages and also Nicolas de Staël, Pierrette Bloch created her first abstract paintings, which were heavily textured and structured using grid compositions.

THE ARTIST PIERRETTE BLOCH’S “YEARS OF WANDERING”

Pierrette Bloch’s work was exhibited for the first time at the Salon des Surindépendants in Paris in 1949. The artist’s first solo exhibition was presented in 1951 at the Galerie Mai in the French capital. Pierrette Bloch’s first solo exhibition in the United States took place in the same year, presented at the Hacker Gallery in New York. The following year, the artist’s work was shown at the French Art of the XXth Century exhibition at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. In 1953, Pierrette Bloch created her first collages and moved into a studio on Rue Antoine- Chantin in the 14th arrondissement of Paris.

In the 1950s, Pierrette Bloch’s work was defined by the importance of rhythm, the balance between fullness and emptiness, and the contrast between black and white. Entering a period that she called her “years of wandering”, the artist withdrew from the art world to her studio.

THE ARTIST PIERRETTE BLOCH’S WORK ON PAPER

The 1960s were a period of investigation and experimentation for Pierrette Bloch, who abandoned painting in 1965 to devote herself to collage. In 1968, the artist spent some time in New York where she created her first collages on paper—Canson, kraft or Bristol—which she mounted on Masonite panels.

In the early 1970s, Pierrette Bloch began working with ink on paper, creating networks of spots and dots on white backgrounds that would become emblematic of her work. At the same time, she experimented with other techniques—using chalk, charcoal, graphite, oil pastels and dry pastels.

THE ARTIST PIERRETTE BLOCH’S WORK IN TEXTILES

The year 1973 marked an important juncture in Pierrette Bloch’s work, as the artist began integrating cords and threads into her work. Pierrette Bloch began creating meshes using hemp in 1978 and adopted horsehair as a material in 1984. These materials would become essential to her work. A textile artist, Pierrette Bloch used weaving, braiding, knitting and embroidery techniques to create paths and lines sometimes reaching up to several metres in length. These minimal sculptural forms were made up of loops running over a taut nylon thread. These works were influenced by the minimalist music that the artist discovered in 1976.

THE ARTIST’S “LINES OF PAPER” AND “PLACES OF UNCERTAINTY’

Pierrette Bloch’s work in relief found its counterpart in the artist’s pictorial work when she created her first “lines of paper” in 1994. In a form of abstract writing, the artist produced loops of ink imitating loops of fibre. Pierrette Bloch’s own writing was also reflected throughout her work, the artist’s poetic texts regularly accompanying her pictorial works.

Bloch also created what she called her “places of uncertainty”, producing boundless arrays of dots in Indian ink on white paper in long-format pieces that could stretch to more than ten metres in length. The theme of repetition played an essential role in Pierrette Bloch’s work, which was characterised by her large formats and economical use of resources.

In 1999, Pierrette Bloch’s work was presented in a retrospective exhibition at the Musée de Grenoble in Grenoble, France, and then at the Musée des Beaux-Arts in La-Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland. In 2002, the Cabinet d’Art Graphique at the Centre Pompidou exhibited the artist’s works, and the following year, a solo exhibition entitled Lignes et crins was presented at the Musée Picasso in Antibes. In 2005, the Fondation Pro-Mahj at the Musée d’Art et d’Histoire du Judaïsme in Paris awarded the Maratier Prize to Pierrette Bloch for her life’s work. In 2009, the Musée Fabre in Montpellier presented a solo exhibition of Pierrette Bloch’s work. The following year, the artist participated in the exhibition On Line at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Pierrette Bloch died on 7 July 2017 in Paris, France.

ROSWITHA DOERIG

(1929-2017)

EXHIBITED ARTWORKS

Roswitha Doerig in her studio, Appenzell, Switzerland

Reserved rights

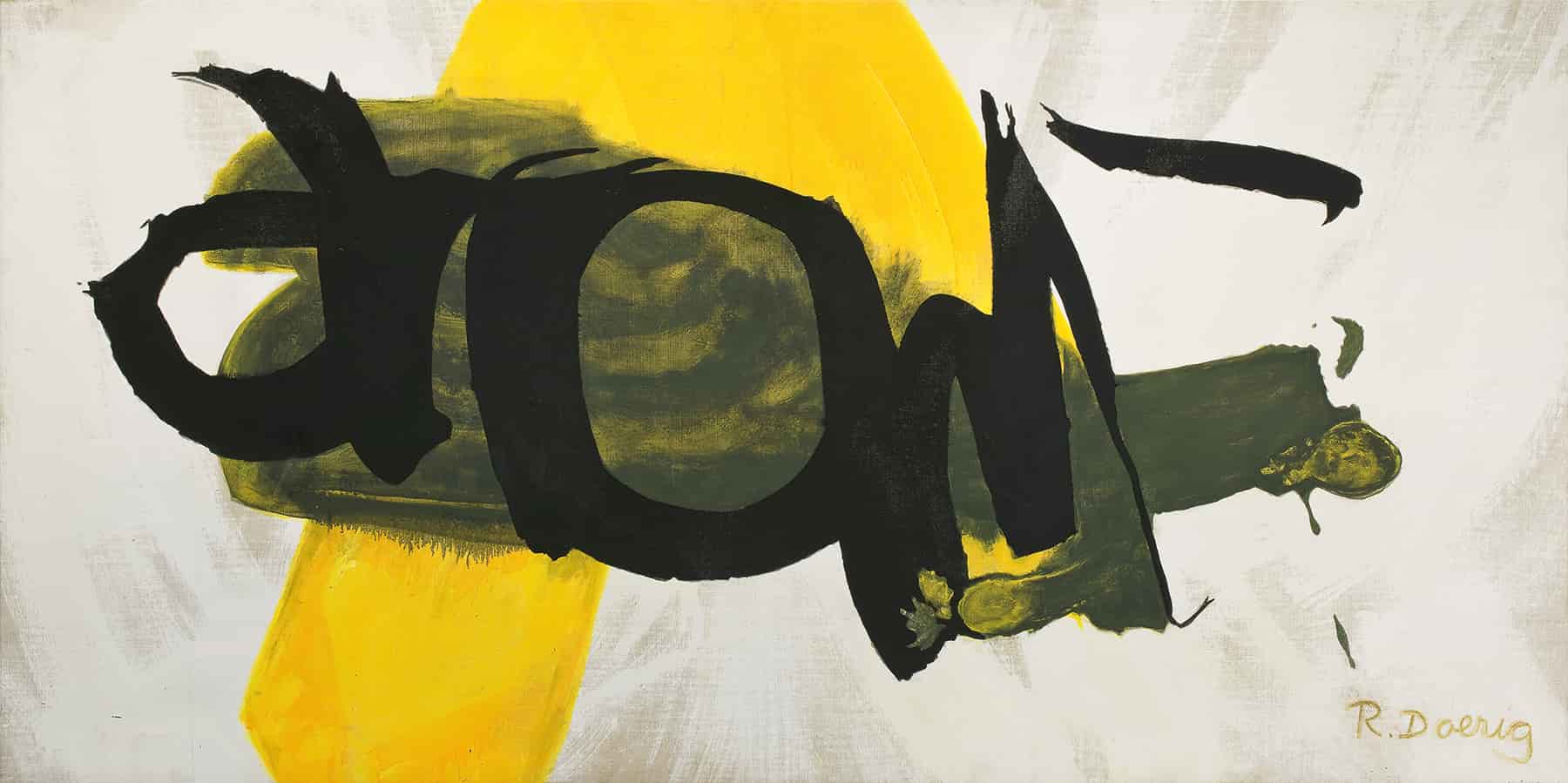

ÉCRITURE JAUNE, 1992

Acrylic on canvas

110 x 220 cm – 43 5/16 x 86 5/8 in.

Signed “R.Doerig” lower right

Galerie Diane de Polignac, Paris

GESTES BLANCS-NOIRS, 2008

Acrylic on canvas

81 x 130 cm – 31 7/8 x 51 3/16 in.

Galerie Diane de Polignac, Paris

UNTITLED, 2012

Acrylic on canvas

54 x 64,5 cm – 21 1/4 x 25 3/8 in.

Galerie Diane de Polignac, Paris

UNTITLED, 2015

Acrylic on canvas

100 x 81 cm – 39 3/8 x 31 7/8 in.

Galerie Diane de Polignac, Paris

BODY FOR WORK ANALYSIS

Roswitha Doerig

“Stepping outside the box”

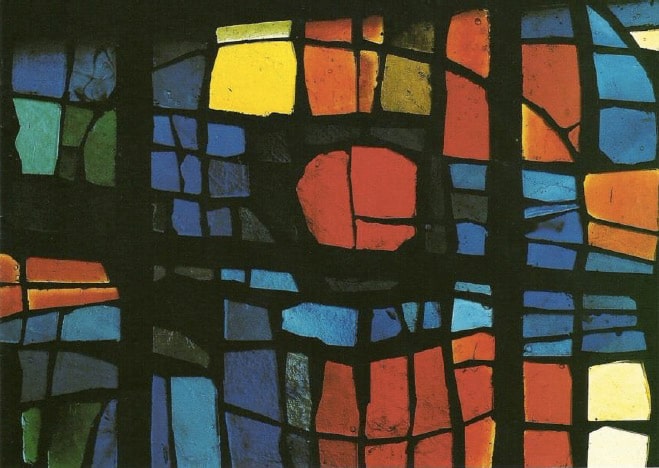

Stained-glass window for the Church of Saint-Paul, Nanterre

(France), 1968 (details)

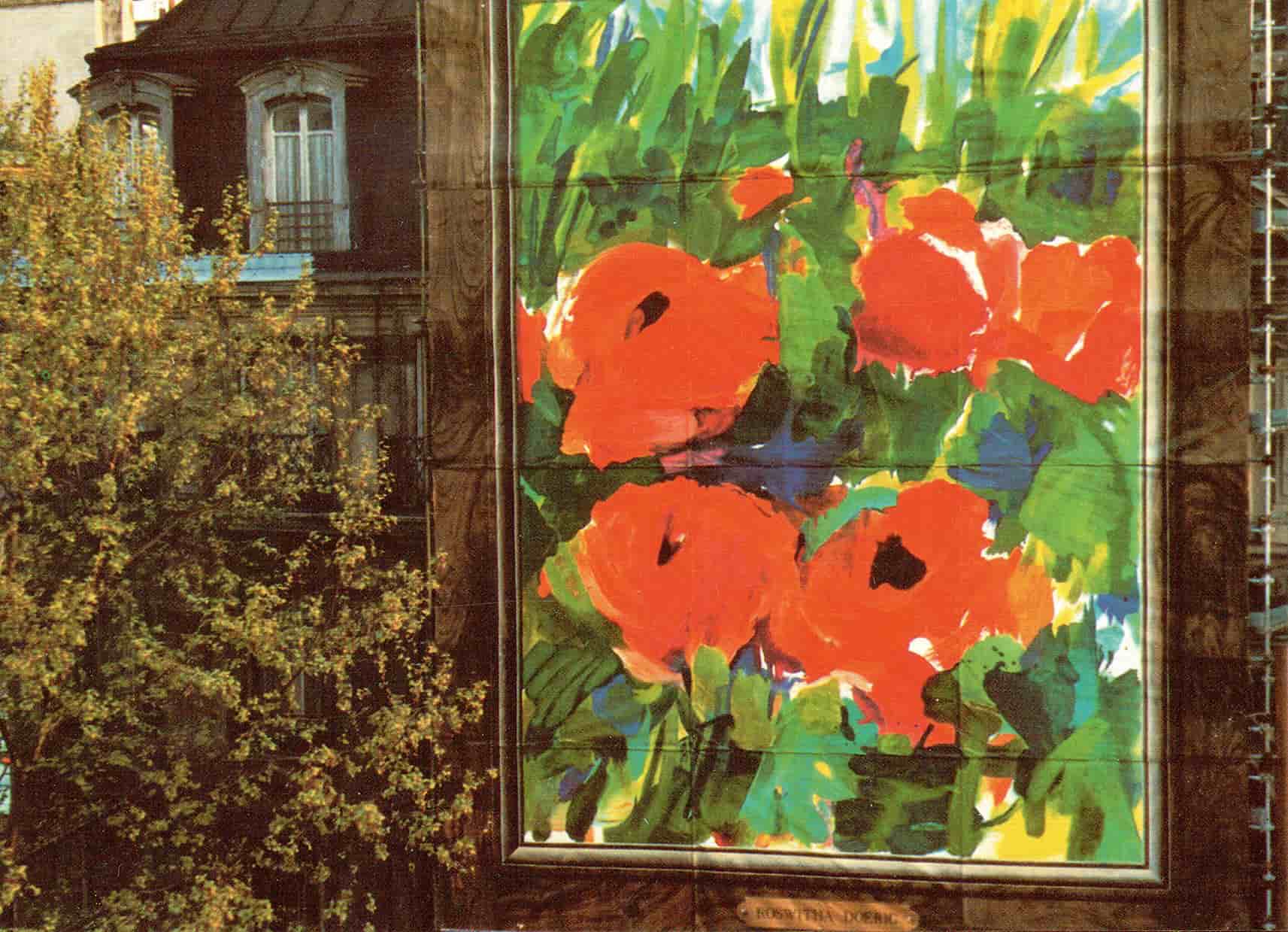

LES COQUELICOTS, 1987,

Painted tarpaulin sheet, 120 m2, Paris

THE ARTIST ROSWITHA DOERIG’S FORMATIVES YEARS

Roswitha Doerig’s art education stands out for two reasons: because of its longevity and its international nature. During the 17-year period from 1947 to 1964, Doerig studied in four different countries, attending the Heatherley Art School in London, the School of Fine Arts in Geneva, Columbia University in New York and the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris.

Three notable figures played particularly important roles in the artist’s formative journey: Ferdinand Gehr (1896–1996), Doerig’s uncle and the painter of religious art whose studio the artist attended for a time in Switzerland; the painter Franz Kline (1910–1962) who was Doerig’s teacher at Columbia University in New York; and Raymond Legueult (1898–1971), her painting teacher at the Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris. These three masters provide an outline of the three central axes of Doerig’s body of work: religious art, gestural expressionism and colour.

The final theme that is characteristic of Doerig’s work is monumental art, which she developed a passion for through her personal journey as an artist. Roswitha Doerig was born in 1929 in the canton of Appenzell Innerrhoden in Switzerland, where women’s suffrage was only granted in 1990. Doerig had to work extra hard to establish herself as a woman artist—she wanted to “step outside the box” from an early age, also a reason why she chose to take on such ambitious monumental projects.

ROSWITHA DOEGIG & CONTEMPORARY STAINED-GLASS WINDOWS

Roswitha Doerig made a name for herself as early as 1968 when she won a competition to create the stained-glass windows of the Church of Saint-Paul in Nanterre, just outside of Paris. Doerig chose abstraction to represent the divine in the project, which was conceived in the context of the events of May 1968 in France. With traditional values being challenged all around her, the artist was encouraged to embrace abstraction, which gave audiences much greater freedom of interpretation. Doerig created her work “as a composition with the other”. The stained-glass window in the chapel was entitled Dieu [God]. Composed with a red circle at its centre, this highly modern representation was inspired by the artist’s uncle, the religious painter Ferdinand Gehr. Like Gehr, Doerig used the symbolism of shapes and colours in her work. A perfect geometric form, without beginning or end, the circle was the ideal shape to evoke the concept of God. Evocative of life-giving blood, the colour red also reminds the viewer of the blood that was shed on the cross, and fire—a traditional metaphor for the divine.

Roswitha Doerig was thus perfectly suited to take her place in a new wave of stainedglass creations that began in the 1960s. With a need to replace works destroyed during the two World Wars, it was not uncommon for contemporary artists to be approached to work on such projects, such as: Marc Chagall, Jacques Villon, Pierre Soulages, Martial Raysse, Alfred Manessier, Joseph Sima, Vieira da Silva and Claude Viallat. It was the golden era of the dalle de verre technique, which became the medium of choice for contemporary art to enter holy places—both ancient and modern.

ROSWITHA DOERIG & ACCESSIBLE ART

In the context of the events of May 1968 in France, many artists felt a desire to create art that was accessible to all, outside of the networks that art was traditionally disseminated through. As art invaded the streets, gargantuan works—the scale of which Roswitha Doerig very much appreciated—were the perfect communication tools. Doerig became very close to the artist couple known as Christo—whom she had met in 1962—and thus took part in the wrapping of the Pont Neuf bridge in Paris in 1985. These experience

This resulted in the creation of two monumental works on tarpaulin sheets: Le Printemps [The Spring] (180 m2) and Les Coquelicots [The Poppies] (120 m2). Installed in 1986 and 1987 respectively in the streets of Paris, the two works were in full view of passers-by. This medium was highly appreciated by artists at the time. These works by Doerig can be likened to the tarpaulin works created in 1968 by the artist Simon Hantaï (1922–2008), who summed up the artistic issue of the time as follows: “The problem was: how to beat the aesthetic privilege of talent, of art, etc.? How to make the exceptional banal? How to become exceptionally banal?” s only strengthened her desire to “step outside the box”.

Not only was the exhibition space brought into question, but also the creative space. Artists had been creating works in public as early as the 1950s—Georges Mathieu (1921–2012), for example, made the very creation of his paintings a real happening. Doerig was part of this movement and enjoyed painting outside of the studio environment in full view of the public. The artist said: “Art is about people, it is a matter of communication”.

The act of painting became a kind of social connection with the audience and the creative process was unveiled and demystified. “We are all called to be creators, this is not only for a few privileged people…” Doerig reflected. Doerig wanted to make the general public less intimidated by art, making the practice of painting accessible to everyone outside of an academic context.

ROSWITHA DOERIG & URBAN ART

The socio-cultural and economic context of the 1960s, as well as the development of new types of paint (acrylic, enamel, aerosol, etc.) led to the birth of urban art. This new form of art broke away from traditional dogma, invading the public space. Monumental frescoes appeared on walls, sometimes the result of personal and illegal initiatives, sometimes commissioned by institutions. The author Daniel Boulogne published Le Livre du mur peint – Art et Techniques on the subject in 1984.

Roswitha Doerig was perfectly suited to find her place in this new era. In 1970, the artist created a mosaic for a residence for young workers in Laval, France. In 1989, Doerig was commissioned to paint a 25 m2 mural for the façade of a factory in Eure-et-Loir, France. Very much at ease with the monumental format, the artist was nonetheless confronted with a new series of technical characteristics and issues. She had to adapt to the material of the wall itself—its accessibility, surface and exposure to light. Specific technical measures had to be put in place, such as scaffolding, wall preparations and the choice of the paintings themselves. This required the artist to conceive her work directly outdoors, in a vertical position and on its final surface. The wall became the work, the space for creative exploration and the exhibition space all at once.

ROSWITHA DOERIG & PAINTING AS THE ULITMATE MEDIUM

The second half of the twentieth century was the age of artistic action, or performance art. Realised outside of traditional dissemination channels, the new movement was defined by the movement of the artist’s body, the importance of the material and the participation of spectators. One of the founding movements of performance art was Gutai—a Japanese art movement that established itself in the world through its performative nature and the importance it gave to the medium.

Concerned with the significance of the medium itself, Doerig also used the medium of painting for herself. Discussing the issue, the artist explained: “I am, of course, delighted when my work provokes an emotional response, but I don’t paint for that purpose. I paint for the sake of painting, just as I don’t want to convey any political or moral ideas. Spiritual quests are also exempt, although my artistic approach to perfection may unconsciously tend towards them. My painting therefore has no goal as such. All that matters to me is to create a beautiful painting. Painting today is conceptual, carrying a message intended to shock or awaken the world, and the art market encourages this conceptual nature. It is not the case for me. I have too much respect for painting to use it in this way.”

ROSWITHA DOERIG & GESTURAL PAINTING

From the 1990s onwards, Roswitha Doerig focused her attention on gestural expressionism and discovered the teachings of the American painter Franz Kline. At the same time, Doerig’s palette gradually became more restricted. The artist used black in contrast with the canvas background, which was painted in white or left unpainted. Adopting the motto “less is more”, Doerig created works during this period somewhat reminiscent of the large black and white canvases of her former teacher Franz Kline, who, on projecting one of his sketches to enlarge it, is said to have been convinced of the autonomous nature of each towering line. It was then that he is said to have moved on to create the large-format canvases and monumental black “scaffolding-style” paintings that are so emblematic of his work. Like the abstract expressionists, Doerig laid her canvas on the ground to paint— no longer standing in front of the painting, the artist was now in the painting. Throughout the artist’s creative process, the work had no preconceived direction. Her gestures were applied in all directions, creating a sense of disorientation and imbalance. The large format that Doerig was so fond of allowed her great physical expressiveness. The creation of the painting became a dance between spontaneity and control. On the subject of her gestural painting, Doerig used to say: “What appears to have been painted with ease is in fact the result of a lot of work.”

Roswitha Doerig

Biography

THE ARTIST ROSWITHA DOERIG’S FORMATIVE

Roswitha Doerig was born into a family of eight children on 25 August 1929 in Appenzell, Switzerland. In 1947, at the age of 18, she went abroad for the first time, enrolling at a boarding school in the Midlands region of England to learn English. Doerig then became a student at the Heatherley School of Fine Art in London, where the American painter Franz Kline had studied ten years earlier—between 1937 and 1938. Franz Kline and Roswitha Doerig will have the same painting teacher: Iain Macnab. Founded in 1845, the Heatherley School of Fine Art became the first English art school to admit women in 1848. After her stay in London, Doerig then returned to Switzerland, where she took classes at the art school in St. Gallen. She also had the benefit of several painting lessons provided by her uncle Ferdinand Gehr (1896–1996)—who is regarded as the most important Swiss painter of religious art in the 20th century. Gehr’s lessons would have a decisive impact on Doerig’s work. The training the artist received from her uncle can explain the presence of certain recurring sacred motifs in her figurative work—the angel motif was of particular

importance to Doerig. Ferdinand Gehr also encouraged Doerig to experiment with the use of colour and explore a modern approach to religious pictorial themes— particularly by mixing elements from sacred iconography with abstract art.

In order to secure an income, Doerig trained as a nurse at the School of Sainte- Agnès in Fribourg, after which she found work at a nursery in Geneva. In Geneva, she grasped the opportunity to attend the city’s School of Fine Arts, where she took evening classes in 1953. In 1954, Roswitha Doerig began working as an au pair for the Busch family, owners of the Budweiser beer company in St. Louis (MO) in the United States. While on the other side of the Atlantic, Doerig seized the chance to enter Columbia University in New York, where she became a student of Franz Kline and discovered the American Abstract Expressionist movement. Kline’s fondness for broad black strokes would have a profound influence on Doerig’s own style of abstract painting. She was also introduced to theatre design, her uncle Ferdinand Gehr having already given her a taste for monumental painting.

ROSWITHA DOERIG’S MOVE TO PARIS

In 1957, Roswitha returned to Europe and settled permanently in Paris. She studied at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in the French capital from 1957 to 1964, taking painting classes taught by Professor Legeult and fresco classes taught by Professor Aujame. She also studied lithography under Professor Jaudon and stained-glass painting under Professor Chevallier. Doerig found it difficult to integrate at the institution, as the artist herself explained: “The students, and even the candidates for the Grand Prix de Rome, had not yet heard of Paul Klee. When I arrived at the studio in the morning, I would find my paintings repainted with notes left next to them, saying: ‘We don’t paint with wild colours here’.” A strict style of formal academicism was still in force at the school, where drawing still prevailed over colour. Doerig complied with the school’s approach to teaching and incorporated the classical canons into her practice. She was, nonetheless, encouraged to pursue her interest in colour by one of her teachers, Raymond Legueult—one of the most important members of the group known as the “Painters of the Poetic Reality”. Legueult awarded Doerig the First Prize for Fine Arts for her “Vacation Works”.

In 1959, Roswitha Doerig was awarded the First Prize for Religious Art by the Galerie Saint-Séverin in Paris. Her work was shown to the American public in the same year as part of a CBS (Columbia Broadcasting System) television programme. Working in a colourful figurative painting style, the artist’s work at the time was focused on the themes of portraiture, still life and landscapes. In December 1962, Doerig had her first solo exhibition at the Hotel Hecht in Appenzell. All the works on show were sold, which enabled the artist to continue her studies.

ROSWITHA DOERIG AND MONUMENTAL ART

In 1964, Doerig created her first monumental work: a fresco entitled Entre Ciel et Terre for the house of Dr Kellerberger in Appenzell. Measuring nearly 9 m high and composed of five panels, the fresco represented a landscape. The composition of the piece was characterised by simple forms and a bright, almost monochrome palette. It showed no desire for imitation—only a desire for expression. The work was hung on the wall of a staircase, where it was gradually revealed to the viewer as they made their ascent. Inspired by her uncle’s paintings, Doerig also found inspiration in the landscapes of Appenzell, saying: “Everything is colourful, starting with the walls of the farmhouses…”. In 1965, Doerig married the architect Serge Lemeslif. The couple had a daughter—Maidönneli.

In 1968, Roswitha Doerig won a competition to design the stained- lass windows of the Church of Saint-Paul in Nanterre, which was designed by the architect Auzenat. Doerig’s first abstract work, the windows brought together the major themes of her creative work: religious art, colour and monumental art. The main stained-glass window of the Church of Saint-Paul was 14 m high and a second, smaller stainedglass window was located in the annexed chapel. These stained-glass windows were made using glass slabs in a modern technique known as dalle de verre developed in 1927. The trend for religious architecture built using reinforced concrete in the 1950s and 1960s popularised the technique, through which glass slabs coloured with metal oxides were shaped with a hammer to create different levels of thickness and thus different light effects. Concrete was used instead of lead to form the supporting framework. Doerig designed these stained-glass windows in France in the very particular context of the events of May 1968. With traditional values being challenged all around her, the artist was encouraged to embrace abstraction, which gave audiences much greater freedom of interpretation. Doerig created her work “as a composition with the other”.

The stained-glass window in the chapel was entitled Dieu [God]. Composing the work with a red circle at its centre, Doerig used abstraction to depict the divine. The creative process was inspired by her uncle, the religious painter Ferdinand Gehr. Like Gehr, Doerig used the symbolism of shapes and colours in her work. A perfect geometric form, without beginning or end, the circle was the ideal shape to evoke the concept of God. Evocative of life-giving blood, the colour red also reminds the viewer of the blood that was shed on the cross, and fire—a traditional metaphor for the divine.

Following on from her experiments with colour and monumental works, Doerig created a mosaic for a residence for young workers in 1970 in Laval, France. Doerig’s work was presented in a string of exhibitions throughout the 1970s, starting with the group exhibition Les 100 de l’école Alsacienne at the Galerie Katia Granoff in Paris in 1974. This was followed by four solo exhibitions: at Appenzell Castle in 1975, at the Bleiche Gallery in Appenzell in 1976, in Batschuns (Austria) in 1978, and at the Fassler Blauhaus Gallery in Appenzell in the same year. The artist also created numerous tapestries during this period.