BERNARD BUFFET

& The bestiary

BERNARD BUFFET

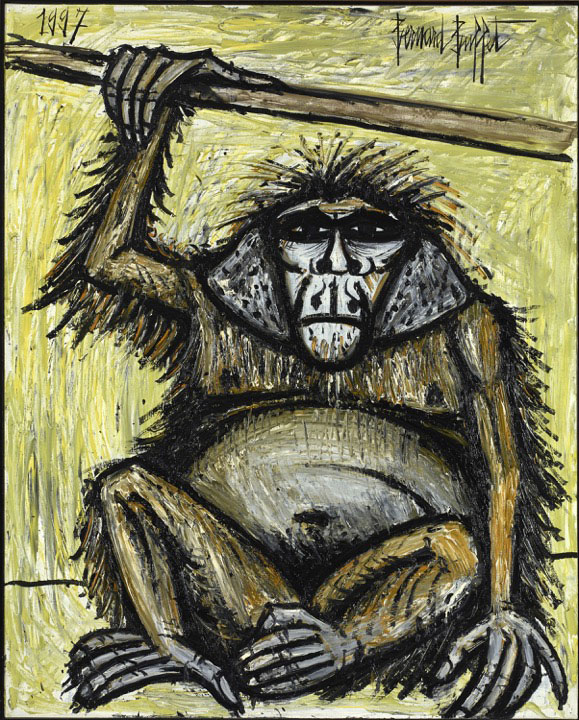

Orang-outan – 1997

Oil on canvas, 162 x 130 cm / 63.8 x 51.2 in.

Diane de Polignac Gallery, Paris

The animal figure runs through Bernard Buffet’s colossal body of work. The artist, who excelled in natural sciences from an early age, brought together the technical prowess of drawing with his angular style to depict the human soul, its feelings and its vicissitudes, through the medium of animals.

BEYOND STILL LIFE

From his earliest works and in the miserabilist style of the 1940s, the animal figure occupied the pictorial realm of Bernard Buffet, marked by a restricted palette with muted tones and an economy of means. As the main characters in his early still lifes, the animals he portrayed, such as Le coq mort and Le Lapin écorché, depict poverty and destitution in a crude fashion. Reduced to carcasses, these gaunt animals reinforce the state of despair that emerges from the still lifes, revealing a cruel form of loneliness and poverty, and provoking a sense of unease and pity in the viewer. By painting the butchered animal, the artist was probing the turpitudes of the soul.

BERNARD BUFFET

Le coq mort, 1947

Oil on canvas, 97 x 114 cm / 38.2 x 44.9 in.

Centre national des arts plastiques, on loan to the Musée Cantini in Marseille

BERNARD BUFFET

Nature morte au lapin écorché, 1949

Oil on canvas, 96 x 94 cm / 37.8 x 37 in.

Stiftung Im Obersteg, on loan to the Kunstmuseum Basel

Following in the footsteps of Jean-Baptiste Siméon Chardin, Bernard Buffet was able to stage the animal kingdom with great majesty. Particularly interested in the aquatic world, Buffet dedicated an entire series of paintings to the theme of Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea by Jules Verne. Among many other subjects, the ray was often used by the artist, depicted in a variety of different styles—from those marked by a great economy of means to more expressionist and bold, graphic styles. The animal became the sole protagonist, occupying the entire surface of the painting, as in the painting Les deux raies.

Jean-Baptiste Siméon Chardin

La Raie, 1728

Oil on canvas, 114 x 146 cm / 38.2 x 57.5 in.

Musée du Louvre, Paris

BERNARD BUFFET

Les Deux Raies, 1963

Oil on canvas, 200 x 300 cm / 78.7 x 118.1 in.

Fonds de dotation Bernard Buffet collection, Paris

THE BESTIARY AS PERSONIFICATION

Bernard Buffet also used animal figures to personify certain human feelings, states of mind and behaviour. Like real portraits, Buffet’s animals were painted like people in his paintings. The entire animal world was explored, from the smallest insect to the largest mammal.

Just like a cabinet of curiosities, his work shows butterflies and other pinned insects, stuffed birds and fish skeletons appearing in different sizes, blurring scales and orders of size. The artist confessed: “My passion for insects developed when I was in the sixth grade, at the Lycée Carnot in Paris. I owe it to my science teacher, Jean Roy: on Thursdays, he took me to the Museum.” This passion even led the artist to dedicate an entire exhibition to the theme: Le Muséum de Bernard Buffet. Held at the Galerie David et Garnier in Paris in 1964, the exhibition reiterated the artist’s devotion to the subject, which had already been featured in the exhibition of drawings entitled Le Bestiaire at the Galerie Visconti in Paris in 1954.

Throughout his work, Bernard Buffet also used animal

figures in his paintings. Far removed from Albrecht Dürer

and his naturalist style, Bernard Buffet’s animals found

expression in a more expressionist vein, with the artist

painting the essential characteristics of each species in

a few brushstrokes..

Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528)

Chouette-effraie, 1508

Watercolour and black ink on

paper, 28.8 x 15 cm / 11.3 x 5.9 in.

Albertina Museum, Vienna

BERNARD BUFFET

Le Petit Duc, 1984

Lithograph in colours on

Arches paper

76 x 57 cm / 30 x 22.4 in.

THE BESTIARY AS A FORM OF ALLEGORY

The animal stands out masterfully against a neutral, plain background. By blurring the scales and setting paintings against each other, Buffet also overturned the attributes and ideas that one might associate with them. By painting and individualising insects and large mammals, the artist put them on an equal footing from the outset. As elegant as it is majestic, the wasp with its long and slender legs is a force to be reckoned with, despite its small and fragile size. In contrast, the clumsy and cumbersome elephant, which is depicted with round graphics and enveloping forms, seems gentle and harmless. With its head forward and paws out, the wolf appears ready to pounce on its prey, cunning and opportunistic. As for the two goats, their tough looks and arched horns reflect a sense of anger and irascibility.

BERNARD BUFFET

Libellule, 1957

Oil on canvas, 78 x 90 cm / 30.7 x 35.4 in.

Diane de Polignac Gallery, Paris

BERNARD BUFFET

Eléphant, 1997

Oil on canvas, 81 x 116 cm / 31.9 x 45.7 in.

Diane de Polignac Gallery, Paris

BERNARD BUFFET

Loup, 1997

Oil on canvas, 73 x 100 cm / 28.7 x 39.4 in.

Diane de Polignac Gallery, Paris

BERNARD BUFFET

Deux boucs, 1987

Oil on canvas, 73 x 92 cm / 28.7 x 36.2 in.

Diane de Polignac Gallery, Paris

MES SINGES: A HUMANISED BESTIARY OR A GALLERY OF SELF-PORTRAITS?

The last exhibition that Bernard Buffet took part in was called Mes Singes. This thematic series, which was presented in Paris in 1999, revived Bernard Buffet’s passion for painting on the theme of animals. The artist presented a whole gallery of several dozen monkeys of all kinds: chimpanzees, gibbons, gorillas, orangutans, howlers, macaques, and more. Painted from the front or in a three-quarter view, the animals display a palette of expressions mixing melancholy, sadness and despair. They are strangely reminiscent of the series of clowns that is so characteristic of Buffet’s work. However, there is nothing clownish or funny about these performers or animals. Their simian expressions reflect the human soul and its torments. Staring at the audience, they inspire viewers to question themselves. They are also reminiscent of Jean-Baptiste Siméon Chardin’s antics, in which the animal apes the man. Just as Bernard Buffet identified himself with his clowns, should this simian gallery be viewed as another gallery of self-portraits? By using the possessive adjective in the title of this series—Mes singes, or ‘My Monkeys’— maybe the artist provides us with a key to understanding the work.

Characteristic of the artist’s final works, these monkeys are depicted in an expressionist style: a strong and trivial kind of painting, worked with the finger or with the handle of the brush, it recalls the bad painting movement that developed in the 1980s.

BERNARD BUFFET

Gibbon, 1997

Oil on canvas, 195 x 130 cm / 76.8 x 51.2 in.

Diane de Polignac Gallery, Paris

BERNARD BUFFET

Orang-outan, 1997

Oil on canvas, 162 x 130 cm / 51.2 x 63.8 in.

Diane de Polignac Gallery, Paris

By using the animal figure, Bernard Buffet portrayed the weaknesses and emotional states of mankind. A way for Buffet to question mankind, it was also a means for the artist to give us a part of himself—a dual key to understanding that continues to encourage us to question ourselves.

Text: Astrid de Monteverde

© Astrid de Monteverde / Diane de Polignac Gallery