Gérard Schneider

From Abstraction to Lyricism

1945-1955

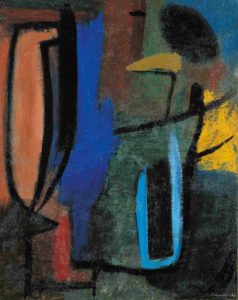

GÉRARD SCHNEIDER

Opus 47 B, 1953

Oil on canvas, 130 x 97 cm / 51.2 x 38.2 in.

“The abstract is pure painting, liberated to translate our internal states to which we give shapes and colours while our elders expressed themselves with and despite the figurative” Gérard Schneider

A pioneer of Lyrical Abstraction with Hans Hartung and Pierre Soulages, the painter Gérard Schneider (1896-1986) was a fundamental figure of the new free gestural abstraction that appeared in Paris in the immediate Post War period.

The Period of Training

Originally Swiss, the artist painter Gérard Schneider settled in Paris in 1922 after studying at the l’École Nationale des Arts Décoratifs and at the École Nationale des Beaux-Arts de Paris in the studio of Fernand Cormon. The 1920s and 1930s were for him a long period devoted to learning the techniques and history of painting: “I covered all the classics” he would repeat. In the middle of the 1930s, Gérard Schneider assimilated the revolution initiated by Kandinsky’s abstraction, while exploring new horizons contributed by Surrealism. He stopped painting from nature in 1935 and from 1938, his titles no longer referred to reality and were simply called Composition. Around 1944, his painting concentrated definitively on a radical abstraction, freed from any connection with the real and visible world.

GÉRARD SCHNEIDER

Untitled, 1944

Oil on canvas, 73,5 x 92 cm

Musée national d’art moderne, Paris

1945-1955: The Years of Experimentation

The years that followed were those of a laboratory of shapes and colours during which the painter Gérard Schneider formed his vocabulary and his style. A transitional period, the decade 1945-1955 was crucial. His experimental abstraction evolved towards the affirmation of his own artistic expression and his controlled, hieratic forms were replaced by a gestural writing that was free and spontaneous, nervous and elated that culminated during the second half of the 1950s: “dramatic abstraction” according to the words of Marcel Brion, which was typical of Schneider.

“After experimenting with all techniques, he reached a point where the shape and colour burst forth. And this revolution happened with great vehemence”. Michel Ragon.

Early Recognition

This is also period when Gérard Schneider began to become known. His work had already been shown in Paris by the leaders of abstract art Denise René and Lydia Conti and now gained international fame. His paintings also circulated around the Federal Republic of Germany in the major travelling exhibition Wanderausstellung Französischer Abstrakter Malerei between 1948 and 1949.

Above all, his art crossed the Atlantic and was shown for the first time in the USA: first at the Betty Parsons Gallery in New York alongside Hans Hartung and Pierre Soulages, in 1949 and 1951; then during the long travelling group show Advancing French Art with venues throughout the country from Washington to San Francisco between 1951 and 1952. It was also on this occasion that Opus 445 entered the Phillips Collection of Washington.

GÉRARD SCHNEIDER

Opus 445, 1950

Oil on canvas, 146 x 97 cm

The Phillips collection, Washington D.C.

The year 1953 was a highlight in this period. Three events promoted the work of Gérard Schneider. Der Spiegel Gallery showed his work for the second time in Cologne.

Schneider also participated for the first time at the International Exhibition of Art in Tokyo. Finally, a first retrospective in a museum was organized at the Brussels Palais des Beaux-Arts.

Extract from the catalogue of the Second International Exhibition of Art in Tokyo, 20 May – 8 June 1953 Schneider’s painting is illustrated alongside works by Hans Hartung and Pablo Picasso

Schneider Retrospective, 12–23 December 1953

Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels

Abstraction as an expression of the interior universe

For the artist painter Gérard Schneider, abstraction does not come from the deconstruction of the object as it was for the Cubist movement but is instead the expression of an internal force. Nothing rational in his approach, but the force of a lyrical temperament that pours out. Neither the surrounding nature nor the deconstructed object inspired him. He was obsessed only by forms that are abstract in themselves, expressive and dramatic. The path of Schneider’s experiments led him first to “abstractize” the (pre-war) shapes and then to “work directly in the abstract” (Michel Ragon) without making reference to the visible world.

“Schneider doesn’t abstract anything. No, he is himself abstrait within the precise meaning given by the Littré dictionary for the past participle that is also an adjective: abstrait – that which has attention only for the internal object that preoccupies it.” Marcel Pobé

Schneider very quickly distanced himself from the geometric style of the post-war period. The object no longer interested him so he did not use geometric shapes in his paintings: no circles or squares appeared in his compositions. Schneider adopted the line that he sourced in the contribution of surrealists’ automatic writing. This line, which became a curve, was auspicious for the spontaneous gesture that would be born later.

“The line is a dominant element, an exercise with speed in which the movement is essential but also this break from nature in which you seek within yourself the source of inspiration. It is surrealism that contributed this, it was very important for the birth of lyrical abstraction and also for the American artists.” Loïs Frederick

Abstraction, in search of form and gesture

“Schneider’s paintings, made with a broad, free gesture in fact come from a certain automatism. Schneider places the brush on the bare canvas that he permeates with a colour that becomes form in the same instant”. Michel Ragon

With Gérard Schneider, form is born by itself, almost like something obvious. But to achieve the mastery of a confident gesture, the artist will fumble, experiment with shapes and colours on the flat surface, in search of a new painting space.

GÉRARD SCHNEIDER

Opus 271, 1945

Oil on canvas, 130 x 97 cm

Private collection, France

First, he painted outlined forms as if they were tangled. “These shapes of which he is the free creator, he limits their freedom instantaneously. They must not escape his control at any cost” wrote Marcel Pobé. This restrained abstraction, which is rigid, nevertheless allows the curve and oblique line to appear in the anthology of forms he proposed, such as in the painting Opus 271 of 1945. But Schneider continued his experimentation and the following year, it was with complete lyrical momentum that he painted Opus 316 in which the colour, a major constituent, is given rhythm by gentle curves.

GÉRARD SCHNEIDER

Opus 316, 1946

Oil on canvas, 92 x 73 cm

Fondation Gandur pour l’Art, Geneva

Between 1947 and 1949, the painter Gérard Schneider experimented with large flat areas with glue that gave substance to organized forms (see Opus 375 of 1948) and rubbed against the principles of monumental painting that he never had the opportunity to apply, as he did not receive any commissions. “For a little while, his art gained from this, a classical firmness, an exemplary monumentality” emphasized Marcel Pobé.

GÉRARD SCHNEIDER

Opus 375, 1948

Oil on canvas, 130 x 162 cm

Private collection, France

Gérard Schneider gradually pursued his quest, all his “arsenal of developed forms” (Marcel Pobé) faded away to be replaced by the sovereign brush that scanned the surfaces.

GÉRARD SCHNEIDER

Untitled, 1952

Gouache, pastel and India ink on paper

36,5 x 53,5 cm

Private collection, France

From Abstraction to Lyricism

The work presented here, Opus 47B from 1953 follows in the wake of these developments. Broad brushes sweep the canvas in powerful creation. Strata of paint layers here work in depth on the colour, sculpting it. First a black form, strong, austere, that debates with the charged skies – emperor blue, indigo and a full palette is used: mauves, straw yellow brushstrokes, emerald green, red streaks, carmine, vermilion and to finish, like an exit, two orange stains on the side.

It is a vertical approach, a solid construction that stands before us, like a medieval statue, possibly an unconscious reminder of the Romanesque sculpture that Schneider especially appreciated.

There is even in these straight, hieratic forms, a distant echo of the tribal masks of African art that were (re) discovered during the 20th century, amongst others through the spectacular collection of tribal art belonging to André Breton, the leader of Surrealism.

Tympanum of the Last Judgment c. 1140-1145

Cathedral of Saint-Lazare, Autun

Songye Anthropomorphic Mask

Quai Branly Museum – Jacques Chirac, Paris

GÉRARD SCHNEIDER

Opus 47 B, 1953

Oil on canvas

130 x 97 cm / 51.2 x 38.2 in.

In Opus 47B, the dominant black gives structure to the composition. In contrast, the white areas, like an intake of air, are a breath. Hollows and full areas are drawn, like a half-round sculpture.

The line appears to be rigid, nevertheless two red stripes, like a scratch on the left side, and this red bite in the centre thwarts this vertical solidity. The equilibrium becomes precarious, which is reinforced by a light white line, added in the centre of the work, sinuous, lazy. Everything is in about to move.

Schneider’s reflexes in painting already emerge from this powerful painting: colour worked in depth by superimposed layers and glazes, broad and powerful brushstrokes and nervous layers that give dynamism to the overall composition. Schneider has here mastered all the elements of his language that will allow him shortly afterwards to free all the power of his “dramatic abstraction”.