Roswitha Doerig

“Stepping outside the box”

Roswitha DOERIG

Écriture jaune, c. 1992

Acrylic on canvas, 110 x 220 cm.

Diane de Polignac Gallery, Paris

Roswitha Doerig was a Swiss painter. Taught by Franz Kline and later a student at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris, the artist created a body of work on the basis of monumental art and the expression of colour and gesture. As an artist, Doerig was fundamentally committed to painting as the ultimate medium of expression.

THE ARTIST ROSWITHA DOERIG’S FORMATIVE YEARS

Roswitha Doerig’s art education stands out for two reasons: because of its longevity and its international nature. During the 17-year period from 1947 to 1964, the painter Roswitha Doerig studied in four different countries, attending the Heatherley Art School in London, the School of Fine Arts in Geneva, Columbia University in New York and the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris.

Three notable figures played particularly important roles in the artist’s formative journey: Ferdinand Gehr (1896–1996), Doerig’s uncle and the painter of religious art whose studio the artist attended for a time in Switzerland; the painter Franz Kline (1910–1962) who was Doerig’s teacher at Columbia University in New York; and Raymond Legueult (1898–1971), her painting teacher at the Ecole Nationale Supérieure des BeauxArts in Paris. These three masters provide an outline of the three central axes of Doerig’s body of work: religious art, gestural expressionism and colour.

The final theme that is characteristic of the artist Roswitha Doerig’s work is monumental art, which she developed a passion for through her personal journey as an artist. Roswitha Doerig was born in 1929 in the canton of Appenzell Innerrhoden in Switzerland, where women’s suffrage was only granted in 1990. Doerig had to work extra hard to establish herself as a woman artist—she wanted to “step outside the box” from an early age, also a reason why she chose to take on such ambitious monumental projects.

ROSWITHA DOERIG & CONTEMPORARY

STAINED-GLASS WINDOWS

The painter Roswitha Doerig made a name for herself as early as 1968 when she won a competition to create the stainedglass windows of the Church of Saint-Paul in Nanterre, just outside of Paris. Doerig chose abstraction to represent the divine in the project, which was conceived in the context of the events of May 1968 in France. With traditional values being challenged all around her, the artist was encouraged to embrace abstraction, which gave audiences much greater freedom of interpretation. Doerig created her work “as a composition with the other”. The stained-glass window in the chapel was entitled Dieu [God]. Composed with a red circle at its centre, this highly modern representation was inspired by the artist’s uncle, the religious painter Ferdinand Gehr. Like Gehr, Doerig used the symbolism of shapes and colours in her work. A perfect geometric form, without beginning or end, the circle was the ideal shape to evoke the concept of God. Evocative of life-giving blood, the colour red also reminds the viewer of the blood that was shed on the cross, and fire—a traditional metaphor for the divine.

The artist Roswitha Doerig was thus perfectly suited to take her place in a new wave of stained-glass creations that began in the 1960s. With a need to replace works destroyed during the two World Wars, it was not uncommon for contemporary artists to be approached to work on such projects, such as: Marc Chagall, Jacques Villon, Pierre Soulages, Martial Raysse, Alfred Manessier, Joseph Sima, Maria Vieira da Silva and Claude Viallat. It was the golden era of the dalle de verre technique, which became the medium of choice for contemporary art to enter holy places— both ancient and modern.

Roswitha DOERIG

Stained-glass window for the Church of Saint-Paul, Nanterre (France), c. 1968

(details)

Claude VIALLAT

Stained-glass window for the Church of Notre-Dame des Sablons, Aigues Mortes (France),, c. 1991 (details)

Simon HANTAÏ and his

Meunsseriess of tarpaulin, 1968

Not only was the exhibition space brought into question, but also the creative space. Artists had been creating works in public as early as the 1950s—Georges Mathieu (1921–2012), for example, made the very creation of his paintings a real happening. The artist Roswitha Doerig was part of this movement and enjoyed painting outside of the studio environment in full view of the public. The artist said: “Art is about people, it is a matter of communication”. The act of painting became a kind of social connection with the audience and the creative process was unveiled and demystified. “We are all called to be creators, this is not only for a few privileged people…” Doerig reflected. Doerig wanted to make the general public less intimidated by art, making the practice of painting accessible to everyone outside of an academic context.

Roswitha DOERIG

Untitled, c. 2014

Acrylic on canvas, 89 x 145 cm.

Diane de Polignac Gallery, Paris

Georges MATHIEU

Karaté, c. 1971

Oil on canvas, 97 x 195 cm.

Musée des beaux-arts de Nantes

ROSWITHA DOERIG & ACCESSIBLE ART

In the context of the events of May 1968 in France, many artists felt a desire to create art that was accessible to all, outside of the networks that art was traditionally disseminated through. As art invaded the streets, gargantuan works—the scale of which the painter Roswitha Doerig very much appreciated—were the perfect communication tools. Doerig became very close to the artist couple known as Christo—whom she had met in 1962—and thus took part in the wrapping of the Pont Neuf bridge in Paris in 1985. These experiences only strengthened her desire to “step outside the box”.

Roswitha DOERIG

Le Printemps, 1986

Painted tarpaulin sheet, 180 m2

CHRISTO

The Pont Neuf Wrapped, 1985

This resulted in the creation of two monumental works on tarpaulin sheets: Le Printemps [The Spring] (180 m2) and Les Coquelicots [The Poppies] (120 m2). Installed in 1986 and 1987 respectively in the streets of Paris, the two works were in full view of passers-by. This medium was highly appreciated by artists at the time. These works by the artist painter Roswitha Doerig can be likened to the tarpaulin works created in 1968 by the artist Simon Hantaï (1922–2008), who summed up the artistic issue of the time as follows: “The problem was: how to beat the aesthetic privilege of talent, of art, etc.? How to make the exceptional banal? How to become exceptionally banal?”

Roswitha DOERIG

working on Le Printemps, 1986

ROSWITHA DOERIG & URBAN ART

The socio-cultural and economic context of the 1960s, as well as the development of new types of paint (acrylic, enamel, aerosol, etc.) led to the birth of urban art. This new form of art broke away from traditional dogma, invading the public space. Monumental frescoes appeared on walls, sometimes the result of personal and illegal initiatives, sometimes commissioned by institutions. The author Daniel Boulogne published Le Livre du mur peint – Art et Techniques on the subject in 1984.

The painter Roswitha Doerig was perfectly suited to find her place in this new era. In 1970, the artist created a mosaic for a residence for young workers in Laval, France. In 1989, Doerig was commissioned to paint a 25 m2 mural for the façade of a factory in Eure-et-Loir, France. Very much at ease with the monumental format, the artist was nonetheless confronted with a new series of technical characteristics and issues. She had to adapt to the material of the wall itself—its accessibility, surface and exposure to light. Specific technical measures had to be put in place, such as scaffolding, wall preparations and the choice of the paintings themselves. This required the artist to conceive her work directly outdoors, in a vertical position and on its final surface. The wall became the work, the space for creative exploration and the exhibition space all at once.

Roswitha DOERIG

Le Vitrail, 1989

Fresco, 25m2.

Eure-et-Loir

Roswitha DOERIG

Untitled, 2012

Acrylic on canvas, 54 x 64,5 cm.

Diane de Polignac Gallery, Paris

ROSWITHA DOERIG & PAINTING AS THE ULTIMATE MEDIUM

The second half of the twentieth century was the age of artistic action, or performance art. Realised outside of traditional dissemination channels, the new movement was defined by the movement of the artist’s body, the importance of the material and the participation of spectators. One of the founding movements of performance art was Gutai—a Japanese art movement that established itself in the world through its performative nature and the importance it gave to the medium.

Concerned with the significance of the medium itself, the artist painter Roswitha Doerig also used the medium of painting for herself. Discussing the issue, the artist explained: “I am, of course, delighted when my work provokes an emotional response, but I don’t paint for that purpose. I paint for the sake of painting, just as I don’t want to convey any political or moral ideas. Spiritual quests are also exempt, although my artistic approach to perfection may unconsciously tend towards them. My painting therefore has no goal as such. All that matters to me is to create a beautiful painting. Painting today is conceptual, carrying a message intended to shock or awaken the world, and the art market encourages this conceptual nature. It is not the case for me. I have too much respect for painting to use it in this way.”

Roswitha DOERIG

Untitled, 2015

Acrylic on canvas, 100 x 81 cm.

Diane de Polignac Gallery, Paris

Takesada MATSUTANI

Cercle 92-1,, 1992

Vinyl adhesive and graphite pencil on paper laid down on canvas

55 x 46 cm

Les Abattoirs, Toulouse

ROSWITHA DOERIG & GESTURAL PAINTING

From the 1990s onwards, the painter Roswitha Doerig focused her attention on gestural expressionism and discovered the teachings of the American painter Franz Kline. At the same time, Doerig’s palette gradually became more restricted. The artist used black in contrast with the canvas background, which was painted in white or left unpainted. Adopting the motto “less is more”, Doerig created works during this period somewhat reminiscent of the large black and white canvases of her former teacher Franz Kline, who, on projecting one of his sketches to enlarge it, is said to have been convinced of the autonomous nature of each towering line. It was then that he is said to have moved on to create the largeformat canvases and monumental black “scaffoldingstyle” paintings that are so emblematic of his work.

Like the abstract expressionists, Doerig laid her canvas on the ground to paint—no longer standing in front of the painting, the artist was now in the painting. Throughout the artist’s creative process, the work had no preconceived direction. Her gestures were applied in all directions, creating a sense of disorientation and imbalance. The large format that Doerig was so fond of allowed her great physical expressiveness. The creation of the painting became a dance between spontaneity and control. On the subject of her gestural painting, Doerig used to say: “What appears to have been painted with ease is in fact the result of a lot of work.”

Roswitha DOERIG

Gestes blancs-noirs II, 2008

Acrylic on canvas, 81 x 130 cm.

Diane de Polignac Gallery, Paris

Franz KLINE

Chief, 1950

Oil on canvas, 148 x 187 cm

MoMA, New York

Roswitha DOERIG

Olivier Messian,, 1994

Acrylic on canvas, 89 x 145 cm.

Diane de Polignac Gallery, Paris

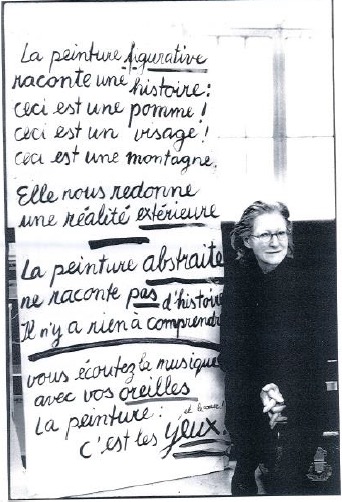

Roswitha Doerig and what “abstract painting” means, 1990

Doerig was certainly an artist of her times. Fuelled by the trends of the second half of the 20th century, the painter crystallised the issues the marked the era. Alongside photography, video and other visual media, Roswitha Doerig is one of those artists who answer the question: how do you continue to paint at the dawn of the 21st century?

Mathilde Gubanski

© Mathilde Gubanski / Diane de Polignac Gallery, 2021