(1929-2017)

Roswitha Doerig was a Swiss painter. Taught by Franz Kline and later a student at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris, the artist created a body of work on the basis of monumental art and the expression of colour and gesture. A versatile artist, she created murals, tapestries, stained-glass windows and mosaics.

Exhibitions

Publications

ROSWITHA DOERIG

Sortir du cadre

Digital publication – Text by Mathilde Gubanski

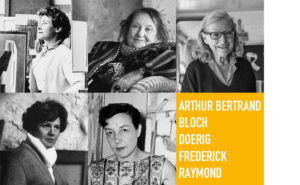

WOMEN IN ABSTRACT ART:

FIVE WOMEN – FIVE ARTISTIC VISIONS

Digital publication – Text by Mathilde Gubanski

Videos

Artwork analysis

The artist Roswitha Doerig’s formative years

Roswitha Doerig was born into a family of eight children on 25 August 1929 in Appenzell, Switzerland. In 1947, at the age of 18, she went abroad for the first time, enrolling at a boarding school in the Midlands region of England to learn English. Doerig then became a student at the Heatherley School of Fine Art in London, where the American painter Franz Kline had studied ten years earlier—between 1937 and 1938. Founded in 1845, the Heatherley School of Fine Art became the first English art school to admit women in 1848. After her stay in London, Doerig then returned to Switzerland, where she took classes at the art school in St. Gallen. She also had the benefit of several painting lessons provided by her uncle Ferdinand Gehr (1896–1996)—who is regarded as the most important Swiss painter of religious art in the 20th century. Gehr’s lessons would have a decisive impact on Doerig’s work. The training the artist received from her uncle can explain the presence of certain recurring sacred motifs in her figurative work—the angel motif was of particular importance to Doerig. Ferdinand Gehr also encouraged Doerig to experiment with the use of colour and explore a modern approach to religious pictorial themes—particularly by mixing elements from sacred iconography with abstract art.

In order to secure an income, Doerig trained as a nurse at the School of Sainte-Agnès in Fribourg, after which she found work at a nursery in Geneva. In Geneva, she grasped the opportunity to attend the city’s School of Fine Arts, where she took evening classes in 1953. In 1954, Roswitha Doerig began working as an au pair for the Busch family, owners of the Budweiser beer company in St. Louis (MO) in the United States. While on the other side of the Atlantic, Doerig seized the chance to enter Columbia University in New York, where she became a student of Franz Kline and discovered the American Abstract Expressionist movement. Kline’s fondness for broad black strokes would have a profound influence on Doerig’s own style of abstract painting. She was also introduced to theatre design, her uncle Ferdinand Gehr having already given her a taste for monumental painting.

Roswitha Doerig’s move to Paris

In 1957, Roswitha returned to Europe and settled permanently in Paris. She studied at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in the French capital from 1957 to 1964, taking painting classes taught by Professor Legeult and fresco classes taught by Professor Aujame. She also studied lithography under Professor Jaudon and stained-glass painting under Professor Chevallier. Doerig found it difficult to integrate at the institution, as the artist herself explained: “The students, and even the candidates for the Grand Prix de Rome, had not yet heard of Paul Klee. When I arrived at the studio in the morning, I would find my paintings repainted with notes left next to them, saying: ‘We don’t paint with wild colours here’.” A strict style of formal academicism was still in force at the school, where drawing still prevailed over colour. Doerig complied with the school’s approach to teaching and incorporated the classical canons into her practice. She was, nonetheless, encouraged to pursue her interest in colour by one of her teachers, Raymond Legueult—one of the most important members of the group known as the “Painters of the Poetic Reality”. Legueult awarded Doerig the First Prize for Fine Arts for her “Vacation Works”.

In 1959, Roswitha Doerig was awarded the First Prize for Religious Art by the Galerie Saint-Séverin in Paris. Her work was shown to the American public in the same year as part of a CBS (Columbia Broadcasting System) television programme. Working in a colourful figurative painting style, the artist’s work at the time was focused on the themes of portraiture, still life and landscapes. In December 1962, Doerig had her first solo exhibition at the Hotel Hecht in Appenzell. All the works on show were sold, which enabled the artist to continue her studies.

Roswitha Doerig and monumental art

In 1964, Doerig created her first monumental work: a fresco entitled Entre Ciel et Terre for the house of Dr Kellerberger in Appenzell. Measuring nearly 9 m high and composed of five panels, the fresco represented a landscape. The composition of the piece was characterised by simple forms and a bright, almost monochrome palette. It showed no desire for imitation—only a desire for expression. The work was hung on the wall of a staircase, where it was gradually revealed to the viewer as they made their ascent. Inspired by her uncle’s paintings, Doerig also found inspiration in the landscapes of Appenzell, saying: “Everything is colourful, starting with the walls of the farmhouses…”. In 1965, Doerig married the architect Serge Lemeslif. The couple had a daughter—Maidönneli.

In 1968, Roswitha Doerig won a competition to design the stained-glass windows of the Church of Saint-Paul in Nanterre, which was designed by the architect Auzenat. Doerig’s first abstract work, the windows brought together the major themes of her creative work: religious art, colour and monumental art. The main stained-glass window of the Church of Saint-Paul was 14 m high and a second, smaller stained-glass window was located in the annexed chapel. These stained-glass windows were made using glass slabs in a modern technique known as dalle de verre developed in 1927. The trend for religious architecture built using reinforced concrete in the 1950s and 1960s popularised the technique, through which glass slabs coloured with metal oxides were shaped with a hammer to create different levels of thickness and thus different light effects. Concrete was used instead of lead to form the supporting framework. Doerig designed these stained-glass windows in France in the very particular context of the events of May 1968. With traditional values being challenged all around her, the artist was encouraged to embrace abstraction, which gave audiences much greater freedom of interpretation. Doerig created her work “as a composition with the other”.

The stained-glass window in the chapel was entitled Dieu [God]. Composing the work with a red circle at its centre, Doerig used abstraction to depict the divine. The creative process was inspired by her uncle, the religious painter Ferdinand Gehr. Like Gehr, Doerig used the symbolism of shapes and colours in her work. A perfect geometric form, without beginning or end, the circle was the ideal shape to evoke the concept of God. Evocative of life-giving blood, the colour red also reminds the viewer of the blood that was shed on the cross, and fire—a traditional metaphor for the divine.

Following on from her experiments with colour and monumental works, Doerig created a mosaic for a residence for young workers in 1970 in Laval, France. Doerig’s work was presented in a string of exhibitions throughout the 1970s, starting with the group exhibition Les 100 de l’école Alsacienne at the Galerie Katia Granoff in Paris in 1974. This was followed by four solo exhibitions: at Appenzell Castle in 1975, at the Bleiche Gallery in Appenzell in 1976, in Batschuns (Austria) in 1978, and at the Fassler Blauhaus Gallery in Appenzell in the same year. The artist also created numerous tapestries during this period.

Doerig’s work in stained glass continued throughout the 1980s, as she created stained-glass windows for the Church of St. Maurice in Murten—near Fribourg in Switzerland—in 1983, as well as stained-glass windows for the restaurants Le Pré Catelan and Le Minotaure in Paris in 1984. It was also a decade marked by solo exhibitions for the artist, who was presented at Appenzell Castle in 1980, the CROAIF (Conseil Régional de l’Ordre des architectes d’Île-de-France) in Paris in 1985, and at the Villa Bianchi Gallery in Uster (Switzerland) in 1987 with the exhibition Roswitha Doerig, Peintures à l’huile, aquarelle, portraits [Roswitha Doerig, Oil paintings, watercolours, portraits].

Roswitha Doerig and Christo

In 1985, Roswitha Doerig began working alongside the artist couple known collectively as Christo, whom she had met in 1962, and went on to take part in the wrapping of the Pont Neuf bridge in Paris—an experience that confirmed her interest in monumental art and deepened her desire to “step outside the box”.

The following year, the artist painted a 180 m2 tarpaulin work entitled Le Printemps [The Spring], which was displayed on Rue de la Harpe in Paris. First developed on a small canvas, the composition of the piece was then transcribed in a larger scale on to the tarpaulin. Due to the dimensions of the work, the artist was obliged to create custom-made brushes to paint with using broomsticks—a technique reminiscent of the stage curtains created by the artist Olivier Debré using brooms during the same period. From then on, the artist Roswitha Doerig abandoned figurative painting altogether, choosing instead to embrace gestural expressionism, which was very much in line with her earlier education among the abstract expressionists.

Doerig repeated the experience in 1987 with a 120 m2 tarpaulin entitled Les Coquelicots [The Poppies]. The work was hung over the façade of the Cluny Palace on the Boulevard Saint-Germain in Paris, where it remained for two months while the façade was being restored. Through these two events, Doerig presented two monumental works to a very wide audience. The artist expressed a desire to bring art out into the street, which was a central issue of the era. She also strove to create images that would be understood by everyone, to avoid indifference at all costs and to maintain that precious connection with the viewer. Discussing the issue, Doerig said: “[Kunst] ist in einer ganz persönlichen Art etwas zu machen und es weiter geben zu können. Kunst hat mit dem Menschen zu tun, es ist Kommunikation” [“[Art], means doing something in a very personal way and being able to transmit it to others. Art is about people, it is a matter of communication”]. Like Christo, Doerig wanted to create a new place for the artist and their work by stepping outside of the official channels that art was disseminated through.

In 1989, Doerig was commissioned to paint a 25 m2 mural for the façade of a factory in Eure-et-Loir, in France. The work was included in the same year in the exhibition L’art sur les murs, which was conceived by the author Daniel Boulogne. The latter had published Le Livre du mur peint – Art et Techniques in 1984. Very much at ease with the monumental format, Doerig was nonetheless confronted with a new series of technical characteristics and issues. She had to adapt to the material of the wall itself—its accessibility, surface and exposure to light. Specific technical measures had to be put in place, such as scaffolding, wall preparations and the choice of the paintings themselves. This required the artist to conceive her work directly outdoors, in a horizontal position and on its final surface. The wall became the work, the space for creative exploration and the exhibition space all at once.

Roswitha Doerig: a socially engaged artist

For Roswitha Doerig, the 1990s began with a solo exhibition entitled Roswitha Doerig Paris Neue Bilder im Fresko at the Neue Staatsgalerie in Stuttgart. In 1992, Doerig moved to Man Ray’s former studio in the Saint Germain des Prés neighbourhood in Paris. “At the start, I was paralysed…” she said.

Doerig was also a socially engaged artist. In 1990, she wrote an open letter following the refusal of the Swiss canton of Appenzell Innerrhoden to grant women the right to vote. In Switzerland, the first cantons granted women the right to vote starting in 1959. The movement spread throughout the country in the years that followed and in 1971, Appenzell Innerrhoden was the only canton still to refuse the right to vote for women. It was only in 1990 that the Swiss Federal Court ruled Appenzell Innerrhoden’s position unconstitutional and introduced women’s suffrage in the canton. Doerig was also critical of the very low presence of women in the art world.

In 1996, Doerig was awarded the Prize for Culture by the Appenzell Innerrhoden Foundation. She was the first woman to be awarded the prize. The artist’s success was followed by a retrospective of her work at the Museum Appenzell and a solo exhibition at the Spisertor Gallery in St. Gallen (Switzerland). The following year, an exhibition dedicated to the artist’s work was held at the Orangerie du Sénat in Paris, where she presented a series of blue and black paintings. Doerig chose blue for its emotive characteristics. With her brushwork contrasting against a white background, the artist also played with different material effects.

This blue period was followed by a red period, during which the artist introduced this new colour to her work through collage. Inserting pieces of paper and cardboard into the paint, her new works were reminiscent of Robert Rauschenberg’s collages, which Doerig had probably observed in New York. Doerig chose a 100 x 80 cm format for these works. Gluing elements onto the surface of the works, the artist challenged the two-dimensional space of the canvas. The series was characterised by a limited palette of black, white, brown and red.

Roswitha Doerig and gestural painting

For Roswitha Doerig, abstraction gave painting “a tremendous freedom”. Her abstract paintings were therefore organised in an almost serialised way in a reflection of her pictorial investigations. She explored colour with the Bleus et Noirs series between 1985 and 1988, materials with the Collages series in 1987, and gestural expressionism with the Gestes series in the 2000s.

It was from the 1990s onwards that Doerig began exploring gestural painting and discovered the teachings of Franz Kline. At the same time, Doerig’s palette gradually became more restricted. She used black, in contrast to the canvas background, which was painted in white or left unpainted. Adopting the motto “less is more”, the artist focused her efforts on gestural expression instead of colour. Doerig’s works from this period are somewhat reminiscent of the large black and white canvases of her former teacher Franz Kline, who, on projecting one of his sketches to enlarge it, is said to have been convinced of the autonomous nature of each towering line. It was then that he is said to have moved on to create the large-format canvases and monumental black “scaffolding-style” paintings that are so emblematic of his work. Like the abstract expressionists, Doerig laid her canvas on the ground to paint—no longer standing in front of the painting, the artist was now in the painting. Throughout the artist’s creative process, the work had no preconceived direction. Her gestures were applied in all directions, creating a sense of disorientation and imbalance. The large format that Doerig was so fond of allowed her great physical expressiveness. The creation of the painting became a dance between spontaneity and control. On the subject of her gestural painting, Doerig used to say: “Was aussieht wie leicht hingepinselt, ist viel arbeit” [“What appears to have been painted with ease is in fact the result of a lot of work”].

In 2000, Doerig created Three in One, a 32 m2 painting in acrylic on canvas for the offices of the Franke company in Aarburg. The work was composed of large colour planes, which were applied to the canvas with her huge custom-made brushes. The canvas background was left white to emphasise the colours layered over it.

In the same year, Doerig declared that monumental painting was an “einer Akrobatikübung” [an “acrobatic exercise”]. The act of painting was at the core of her artistic reflections. There are many photos and videos documenting Doerig painting in public or on the street. The act of painting became a form of social connection with the audience. The artist brought together pictorial creation and performance, unveiling and demystifying the creative process. Observing the artist’s body in movement, the viewer was inspired to participate in the work and to decipher the creative process. The audience identified with the artist. This was very important for Doerig, who said: “We are all called to be creators, this is not only for a few privileged people”. Doerig put this approach into practice in 2004 at the Museum Night in St. Gallen, where passers-by were invited to participate in the creation of one her works. The artist put a canvas on the ground, thus giving members of the public an opportunity to explore an informal approach to painting. Doerig wanted to make the general public less intimidated by art, making the practice of painting accessible to everyone outside of an academic context. Discussing Doerig’s work, a journalist wrote: “Der Betrachter leistet so, auf seiner Weise und auf seiner Seite, das Gleiche wie der Künstler. Dieser Weg führt, aus dem Ende in den Anfang finden, zur Verständigung” [“The viewer, for their part and in their own way, thus does the same thing as the artist. This path leads, from beginning to end, to understanding”]. These concerns, which were very much central issues at the time, were undoubtedly linked to the discovery of mirror neurons by researchers in Parma, Italy, in the 1990s. These neurons are activated during the observation of an action. They teach us to put ourselves in the place of another individual and to imitate them. These discoveries established a fundamental connection between empathy and aesthetic perception. When observing a painting, the viewer not only feels empathy for the characters depicted in the piece but also, in the case of an abstract painting, for the artist. The viewer is able to retrace and feel the artist’s brush strokes themselves.

In 2001, Roswitha Doerig was invited to speak at the World Economic Forum in Davos (Switzerland) as a Cultural Leader. A string of exhibitions followed in France and Switzerland. Together with the curator of the Museum Appenzell, Dr Roland Scotti, the artist published her biography … älter werde ich später [I will grow old later] in 2016. Roswitha Doerig died in Paris on 27 February 2017 and was buried at the Montparnasse cemetery.

© Diane de Polignac Gallery

Translation: Jane Mac Avock

SELECTED COLLECTIONS

Selected Collections

Appenzell, Kunstmuseum

SELECTED EXHIBITIONS

Selected Exhibitions

Group exhibition (?), International House, New York 1955

Works by Roswitha Doerig were presented in a television programme broadcast by the CBS network, New York, 1959

First Prize for Religious Art, exhibition at the Galerie Saint-Séverin, Paris, 1959

Galerie J L Barrault, Paris, 1960

Solo exhibition, Hotel Hecht, Appenzell, 1962

Les 100 de l’école Alsacienne, group exhibition, Galerie Katia Granoff, Paris, 1974

Roswitha Doerig, solo exhibition, Appenzell Castle, 1975

Solo exhibition, Bleiche Gallery, Appenzell, 1976

Solo exhibition, Batschuns, Austria, 1978

Solo exhibition, Fassler Blauhaus Gallery, Appenzell, 1978

Solo exhibition, Appenzell Castle, 1980

Solo exhibition, CROAIF (Conseil Régional de l’Ordre des Architectes d’Ile-de-France), Paris, 1985

Roswitha Doerig, Peintures à l’huile, aquarelle, portraits [Roswitha Doerig, Oil paintings, watercolours, portraits], Villa Bianchi Gallery, Uster, Switzerland, 1987

Group exhibition, Artothèque Passionnariat, Charenton-le-Pont, France, 1990

Roswitha Doerig Paris Neue Bilder im Fresko, Neue Staatsgalerie, Stuttgart (Germany), 1991

Artistes Suisses de Paris, group exhibition, Palais des États de Bourgogne, Salle de Flore, Dijon, France, 1991

Group exhibition, European Gallery, Hall of Honour at the University of Fribourg, Fribourg (Switzerland), 1994

Kunstwoche i de Gass, Appenzell Zunft, group exhibition, Hotel Löwen, Appenzell, 1995

Prize for Culture from the Appenzell Innerrhoden Foundation. Roswitha Doerig was the first woman to be awarded the prize, 1996

Roswitha Doerig Paris Appenzell, retrospective exhibition, Museum Appenzell, Appenzell, 1997

At the presentation of the Culture Prize, Spisertor Gallery, St. Gallen (Switzerland), 1997

Group exhibition, Le 6ème Ateliers d’Artistes, stamp design, Paris, 1997

Roswitha Doerig, Orangerie du Senat, Jardin du Luxembourg, Paris, 1997

Sonja Amsler Roswitha Doerig, Galerie für Gegenwartskunst, Bonstetten (Switzerland), 1998

Roswitha Doerig, Surset – Art Tapisserie, Werkstätte für zeitgenössische Tapisseriekunst [Contemporary tapestry art workshop], Frastanz-Felsenau (Austria), 1998

Roswitha Doerig, Appenzell – Paris, Neue Arbeiten, Zäune 8 Gallery, Zurich, 2000

Peintures récentes, Town Hall, Garches (France), 2000

Roswitha Doerig – Johann Hautle, Zwei Appenzell Charakterköpfe (Two famous figures from Appenzell), Ernst Hohl & Co., Zurich, 2001

Cultural Leader of the WEF, solo exhibition, World Economic Forum, Davos (Switzerland), 2001

Sonja Amsler Borgemeester, Roswitha Doerig, Ursula Fehr, Galerie für Gegenwartskunst Elfi Bohrer, Bonstetten (Switzerland), 2002

Les Artistes suisses, membres de l’association, exposent à la Mairie du 6e arrondissement, group exhibition, Town Hall of the 6th arrondissement, Paris, 2006

Kunst am Bau, Bilder von Roswitha Doerig, solo exhibition, Lassalle-Haus Bad Schönbrunn, Edlibach (Switzerland), 2009

Roswitha Doerig neue Bilder (new works), solo exhibition, Hodler Gallery, Thun (Switzerland), 2009

Invité 2010 – Appenzell, Swiss Pavilion at the Cité Internationale Universitaire, Paris, 2010

Roswitha Doerig, Swiss Embassy, Paris, 2011

Roswitha Doerig und Franklin Zuñiga, Tolle Gallery – Art und Weise, Appenzell, 2014

Roswitha Doerig, Cultural Foundation of the canton of Thurgau, Frauenfeld (Switzerland), 2014

Roswitha Doerig Paris Appenzell, solo exhibition, Galerie Obertor, Chur (Switzerland), 2017

Roswitha Doerig, Town Hall of the 1st arrondissement, Paris, 2017

XIXe Biennale des Artistes du 6e arrondissement, Town Hall of the 6th arrondissement, Paris, 2018

Philippe Hurel, Manufacture des Tapis de Bourgogne, Paris, 2018

Solo exhibition, Widmer Gallery, St. Gallen (Switzerland), 2018

Exposition de l’Avent, solo exhibition, Töpferei & Galerie zur Hofersäge, Appenzell, 2018

Selected works in public spaces

Selected works in public spaces

Entre ciel et terre, fresco for the house of Dr Kellerberger, Appenzell, 1964

Stained-glass windows for the Church of Saint-Paul, Nanterre, 1968–1969

Mosaic for a residence for young workers, Laval, France, 1970

Stained-glass windows for the Church of Saint-Maurice, Murten (Switzerland), 1983

Stained-glass windows for the restaurant Le Pré Catelan, Paris, 1984

Stained-glass windows for the restaurant Le Minotaure, Paris, 1984

Le Printemps, acrylic on a 180 m2 tarpaulin sheet, Paris, 1985–86

Collaboration with Christo and Jeanne-Claude for the Pont Neuf Wrapped in Paris, 1985

Les Coquelicots [The Poppies], lacquer on a 120 m2 tarpaulin sheet, Paris, 1987

Le Vitrail, 25 m2 wall painting on a factory wall, Eure-et-Loir (France), 1989

Three in One, acrylic on canvas, 800 x 400 cm, offices of the Franke company, Aarburg (Switzerland), 2000

Fresque rouge, noire et jaune [Fresco in red, black and yellow], acrylic on concrete, 159 x 1,200 cm, Rehetobel (Switzerland), 2007

Two tapestries in the Hofwies school, Appenzell, 2014

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

Selected Bibliography

“Roswitha Doerig entwarf Kirchenfenster in Paris Nanterre” [“Roswitha Doerig designed stained-glass windows for a church in Paris-Nanterre”], 1968

Roswitha Doerig, “Christo zerstört eine Gewohnheit” [“Christo destroys a custom”], in Appenzeller Volksfreund, 1985

Olivia Phelip, “L’empire de la couleur”, in Architectes, No. 156, April 1985

A. Patry, “Diese Bilder sind froh” [“These works are happy”], in Appenzeller Volksfreund, April 1985

Hans Jürg Etter, “Die Kunst macht die Welt bewusster” [“Art makes the world more aware”], in Appenzeller Volksfreund, November 1986

“Roswitha Dörig in Paris”, in Onder üs, 9. Jahrgang, No. 30, July 1987

Roswitha Doerig, Speech for the Alliance Française in St. Gallen, 1990

Ingrid Burger Schukraft, “Ich kann nur das malen, was ich fühle” [“I can only paint what I feel”], in St. Galler Tagblatt, 1993

Walter Koller, “Frohe Engel une faszinierende Krippen” [“Joyful angels and fascinating nativity scenes”], in Appenzeller Zeitung, 1994

Roswitha Doerig, “Christo gibt mir Mut, auch zu wagen” [“Christo gives me the courage to be daring too”], in Appenzeller Volksfreund, 1995

Max Reinhard, “Moderne Kunst verständlich machen” [“Making modern art understandable”], in Appenzeller Volksfreund, 1996

Vincent Philippe, “Une Appenzelloise à Paris”, in 24 Heures, 1997

Ursula Litmanowitsch, “Akrobatische Malerei” [“Acrobatic painting”], in Thurgauer Zeitung, 2000

Roswitha Doerig, Speech at the World Economic Forum in Davos, 2001

Roswitha Doerig, Speech for the inauguration of a wall painting in Frauenfeld, 2002

Markus Schöb, “Schwarz lässt die Farbe rundherum singen” [“Black makes colour sing all around”], in Appenzeller Zeitung, 2002

Monica Doerig, “Museumsnacht : Roswitha Doerig lud zum Malen ein” [“Museum night: Roswitha Doerig invited to paint], in Appenzeller Volksfreund, September 2004

René Bieri, “Roswitha Doerigs ‘Knochenarbeit’” [“The ‘back-breaking’ work of Roswitha Doerig”], in Appenzeller Zeitung, February 2005

Louise Doerig, “Neues Wandbild von Roswitha Doerig” [New fresco painting by Roswitha Doerig], in Appenzeller Zeitung, 2007

Aline Clément, Roswitha Doerig : Enjeux et fonction de la peinture non figurative à la fin du XXe siècle, Master’s thesis, Paris, November 2013

Roland Scotti, Roswitha Doerig, … älter werde ich später, [I will grow old later], Heinrich Gebert Kulturstiftung, 2016

Roswitha Doerig Faq

On the ROSWITHA DOERIG FAQ page, find all the questions and answers dedicated to the modern art painter Roswitha Doerig.