WOMEN IN ABSTRACT ART:

Five women – Five artistic visions

EXHIBITION : 8 MARCH – 16 APRIL 2021

This exhibition intends to show women’s contributions to abstract painting by presenting a selection of five artists: Marie Raymond (1908–1989), Huguette Arthur Bertrand (1920–2005), Pierrette Bloch (1928–2017), Roswitha Doerig (1929–2017) and Loïs Frederick (1930–2013). These five artists constitute neither a school nor a movement, representing instead five different forms of abstraction, five hard-won freedoms.

To introduce our exhibition, we are delving into the world of each artist by examining one of their works of art.

Chapter 2:

Huguette Arthur Bertrand, Cela qui gronde

By Astrid de Monteverde

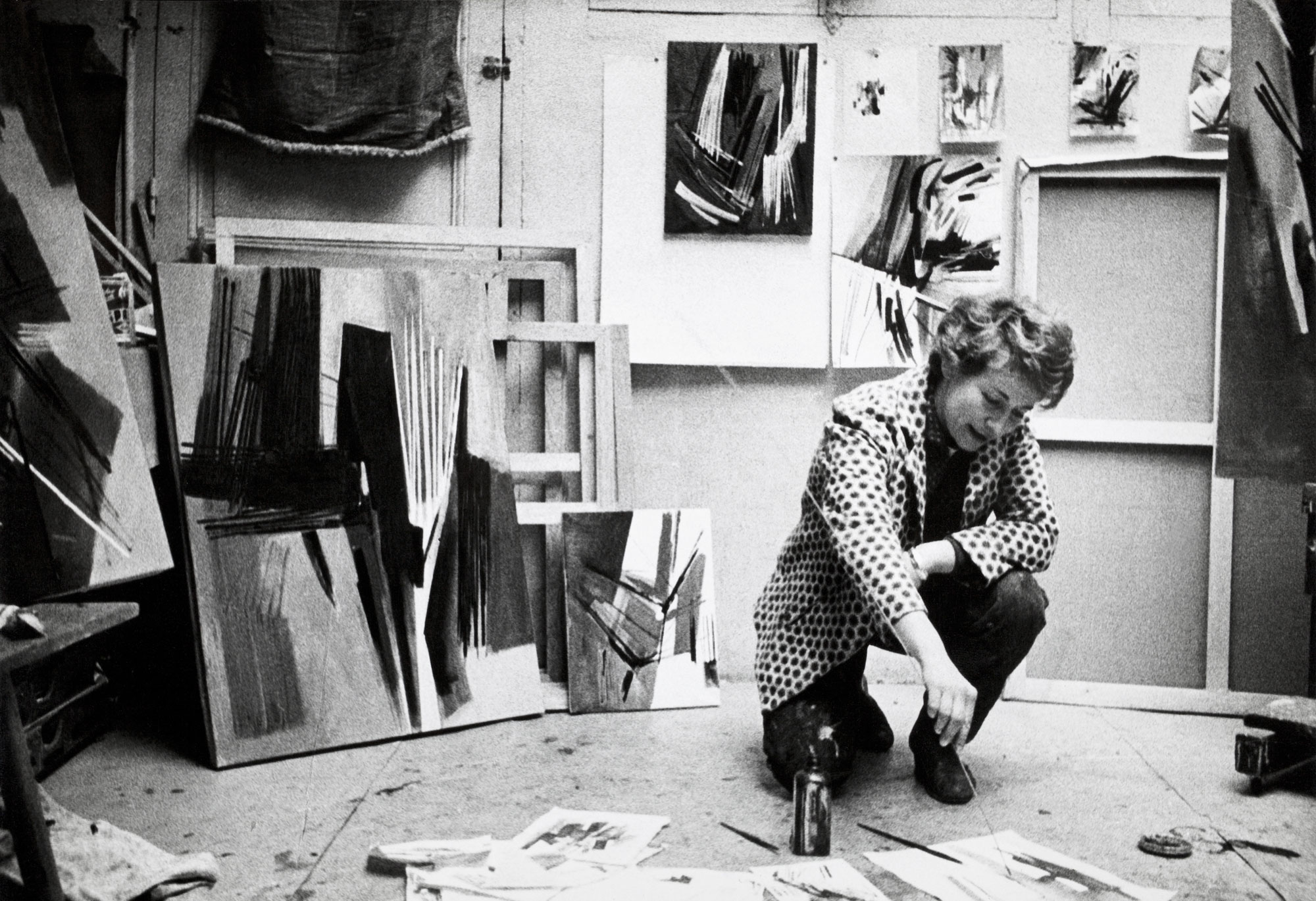

Huguette Arthur Bertrand in her studio, Paris, 1954

Photo: Michel Ragon – rights reserved

Born in 1920 in Écouen, the painter Huguette Arthur Bertrand settled in Paris shortly after the war. She immersed herself fully in the buzzing art world of Montparnasse and Saint-Germain-des-Prés marked by lively debate between figurative and abstract art, but also between supporters of “cold” abstraction and those of “warm” abstraction: one geometric, the other gestural, lyrical, guided by a free and spontaneous gesture.

Huguette Arthur Bertrand became friendly with publishers, critics and abstract artists, and assert herself within this second generation of Lyrical Abstraction artists, born in the 1920s: François Arnal, Martin Barré, Pierre Dmitrienko, James Guitet, John Franklin Koenig, Kumi Sugaï… and some Cobra artists: Corneille and Jacques Doucet. Within this group of friends, mostly male, with whom she exhibited, the painter Huguette Arthur Bertrand was a rare woman artist. A desire to assert her position therefore, to the point of adding a masculine first name to her signature and to truncate her birth name: “Hug” to give it authority.

During the 1960s, the artist painter Huguette Arthur Bertrand deployed the confidence and power of her creative gesture. She abandoned her rigid manner made of sharp streaks and adopted a black brush, free like a dance, sweeping the canvas in a lithe and vigorous movement. It is clear that she was fascinated by dynamism in space at the time. The material counted little. Diluted, the oil paint she used primarily allowed her to give structure to the composition using large coloured areas, often with warm tones such as vermilion red and orange-red: these provided the support for her lyrical impetus. Opposing forces were used. The rigour of the composition, which had always been a preoccupation for her from the start, was contrasted with a free impulse, an enflamed, exalted gesture. The artist worked on her compositions in depth and the vigour of the brush applied to the canvas made the forms move, like “movements that divide space [1]” as the artist said herself.

[1] RTF/ORTF, Jean-Marie Drot and Christian Heidsieck, “L’art et les hommes”, L’oeil d’un critique with Michel Ragon, programme broadcast on 4 February 1962, including an interview with Huguette Arthur Bertrand

In her work, the viewer above all enters into the drama, the theatrical, relating to the stage. At the meeting of elementary forces, the painter Huguette Arthur Bertrand’s work moves, animates itself in an entirely operatic power. The elements are unleashed: rain falls, wind blows, thunder roars. Her vehement titles illustrate this: Raz de marée, Cela qui souffle, Cela qui gronde, Foudre, Torrent… It is not at all surprising that her loyal friend, the art critic Michel Ragon, wrote, when describing her art: “Strong painting, painting of a dynamism that would appear masculine.2”

The artwork Cela qui gronde (That which rumbles) is a perfect illustration of her art during the 1960s. The range of warm colours accompanies the vigour of the brush applied to the canvas to express the exalted lyricism.

[2] RTF/ORTF, ibid